Art as a “textbook of life”

The unforgettable Art Exhibition “Russian Painting in the 19th Century” in the Kunsthaus Zurich in 1989, gives evidence of its great significance just at our present time. In view of the wars, the injustices and current social tensions, there is an urgent need of reflection on a peaceful coexistence and on the related moral and ethical basic values. An impressive example is the “Cooperative of Travelling Exhibitors”. Peaceful solutions to conflicts and a dialogue between people, cultures and civilizations on an equal footing are the order of the day. In Russia, during the important historical period from 1850 to 1910 the relationship between Russia and Europe was consolidated. The common heritage of Christianity, Renaissance and Enlightenment, with its great thinkers and philosophers, had a unifying impact. Russia has its geographical, historical, cultural and political roots in this historic Europe. Trade, scientific exchange and diplomatic relations are important for all European countries. Meaningful cooperation has always been a common concern and should be given more importance again. Instead of today’s EU centralism and of transatlantic dictation, more democracy, autonomy, cultural identity and sovereignty of the nation state have to be achieved again.

The years 1850 to 1870 marked a creative peak among the great painters and writers of Russia such as A. S. Pushkin, N. W. Gogol, I. S. Turgenev, A. P. Chekhov. In 1851, the railway line St. Petersburg-Moscow, at that time the longest in the world, was opened. In 1850, Tsar Nicholas I. ruled over the Russian Empire. Leo Tolstoy was 22 years old, Feodor Dostoyevsky 29 and N. G. Chernyshevsky 22. Chernyshevsky minted the term “culture as a textbook of life”. Hence art was given a social task which also strengthened democratization. Thus, the population, many intellectuals, artists and writers in the mid-19th century were concerned about poverty, social injustice and the peasantry’s needs. In the thereby developed revolutionary movements the focus was on the struggle between liberal and authoritarian forms of society and the view of man. Poets, painters and musicians, “started out to bring the Russian peasants and craftsmen to the center of their attention and to poetize their way of life and their daily work” (p. 61), as the Russian art historian Lindija I. Iowlea writes in the exhibition catalog about the concerns of the Peredvizhniki and their cooperative exhibitions.1 So the artists began to work in the open air, like their French fellows J. F. Millet and G. Courbet in the Barbizon school. It was also an expression of real solidarity with the population, with its culture and with inherent natural beauty.

Relating to the population’s joys and sufferings

The painters calling themselves “Peredvizhniki”, the “Cooperative of Travelling Exhibitors” placed these topics at the center of their work. With their works the “travelling painters” trekked from the cities to the rural population in the remotest regions of Russia. Through their exhibitions they enabled the people there to participate in these cultural activities. They aroused great interest, because in their beautiful paintings they highly appreciated these people and their cultural way of life. Due to the visual language of realism, their contents were generally understood. They seriously entered into dialogue with the population. The major part of Russia’s population were peasants, often living in degrading dependence. The climatic conditions were also harsh. Occasionally, agricultural work could be done merely during four or five months. Famines were common. In his poignant article “The famine in Russia” Leo Tolstoy depicted the people’s misery and great need and he also proposed new ways to ease the latter. In 1861, serfdom was abolished by Tsar Alexander II, pressured by the social developments and the writers’ work who were striving for more social justice and humanity. More rights and liberties were granted to 25 million farmers, many social problems, however, continued to exist.

Truthfulness, meaningfulness and moral values

W. G. Perov was the important representative of the “Moscow realistic school”. With great compassion this “poet of sorrow” raised everyday situations, social inequalities and human tragedies to the general human level, for instance in his picture “The Drowned” ocreated in 1867.

Many younger artists, who were well trained in the tradition of classicist academicism at the St. Petersburg Academy of Art, searched for their own ways. Their focus was on truthfulness, meaningfulness and moral values. The themes of Romanticism with their search for “fathoming the truth of life and of human character” were also important. The driving force were painters like K. P. Bryullov or A. A. Ivanov, who created the great work “Christ appears to the people”, on which he worked for twenty years, namely from 1837 to 1857. You can admire this great painting in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow. The artist wanted to show ethical and moral values which were important for the tasks and the existence of a society. This was associated with the reverence for nature and landscape. These painters considered progress to be the striving after “perfecting the moral principles of the lives of every human being, even of society as a whole”. This search for meaningfulness and social justice was crucial: “In the autumn of 1863, a group of students of the St. Petersburg Academy of Fine Arts in their final year refused to paint the picture for their final competition with a predetermined topic (‘Feast of the Gods of Valhalla’), and demanded free choice of subjects.” (p. 61) This extraordinary event went down in history under the name “revolt of the fourteen”. The demands of the students were rejected, whereupon they left the academy and founded the first independent association of artists in Russia, named the “St. Petersburg Artists’ Association”. It became the predecessor of the “Cooperative for Traveling Exhibitions of Visual Arts” which was launched seven years later. Later it was abbreviated to “Cooperative of Traveling Exhibitors” (Peredvizhniki). In her profound contribution Lidija I. Iowlewa writes: “The establishment of this very important and, in the history of Russian art, also permanent organization is of the utmost historical importance, since it represents the dawn of a new era of the enhanced reference to society.” (p. 66) The works of art were no longer kept in the buildings of the Academy for only a few people, but were made generally available by the enhanced relation to the questions of life of the people. So not only the people in the great cities but also the people in the so far untapped province came to enjoy these pictures and the “textbook of life”.

Social bonding as a vital principle

One of the founders of the cooperative was the artist I. N. Kramskoy, who from 1872 onwards became famous with his portraits and the painting “Christ in the Desert”. He succeeded in raising the religious motif onto philosophical and general human level. High moral and ethical ideals were central and the unifying principle underlying the work of the different personalities of the Peredvizhniki. One of the most original artists was N. N. Ge, a friend of A. I. Herzen and M. A. Bakunin. He was also one of the founding members of the cooperative. In his famous picture “Peter I interrogates Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich in Peterhof” (1871) he succeeds in profoundly representing a momentous interpersonal situation with uncompromising realism. In the late 1870s, he made friends with Tolstoy and accomplished a series of pictures, in which Tolstoy’s moral and philosophical doctrine was central.

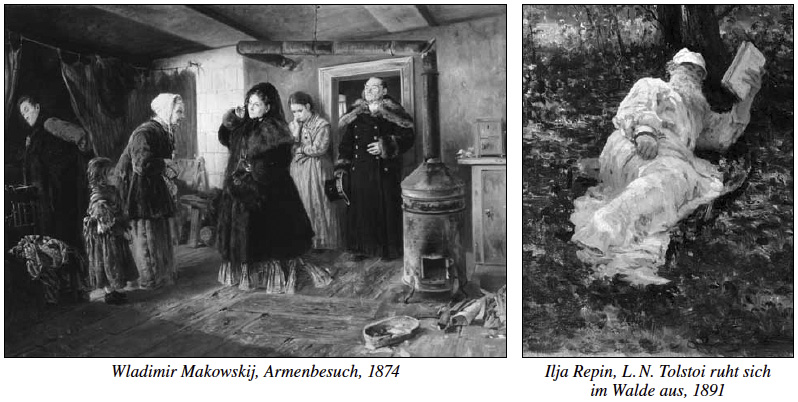

The images of W. I. Surikov and W. M. Maximov, such as his masterpiece “Sick Man” (1881) also treat “humanistic“ themes in a very sensitive manner. In his genre paintings W. J. Makovsky included also the urban social classes and revolutionary intellectuals. His impressive picture “The soiree” (1875–1897) shows a table at which many people are assembled listening to a poetry reading in a scarcely illuminated room. As early as that these artists recognized the necessity of including the psychological dimension in order to understand interpersonal and social processes: “Striving to serve the ‘real interests of the people’ (I.N. Kramskoi), the Peredvizhniki sought a broader definition of art than just the presentation of scenes from among the people. They realized that the image of contemporary life cannot be complete without the representation of the inner life of man, at these times ‘of issues and newspapers’ (Kramskoi).”

The representation of nature and landscape paintings enjoyed great popularity. Here again, credibility, realism and accuracy of monitoring were important. In their works of art the painters were also searching for the soul and “humanity”, even though people did not always appear. “Many landscape paintings were in their character ‘lyrical manifestations’ of the artist, an expression of his feelings and inner life, a reflection on the fate of his country and the people.” (p. 71) Thus, the works of I. I. Levitan show “the wealth of nature in a hitherto unprecedented diversity and illustrate the harmony between nature and human soul. Levitan’s landscapes are not only images of nature but sensitive representations of various mental states and emotions of the people.”

In historical paintings, painters like N.N. Ge, Ilya Repin and W.I. Surikov sought – apart from historic truthfulness – “to capture history in its general human, moral and ethical importance”. But the “roots of national independence” were also emphasized. They contributed decisively to the rooting of democratic ideas. The central figure of the entire group and of Russian art in the second half of the 19th century was Ilya Repin. Well-known are his masterpiece “Barge Haulers on the Volga” (1870–1873) and his paintings and portraits of Tolstoy. With his extraordinary artistic skills he mastered all themes of art. It was “his boundless love for life and his insatiable curiosity for all its phenomena, the interest and attention towards his fellow human being, an almost ‘Tolstoyan’ ability to sense the inner life of another person, and the artistic skill to always find new methods to make these inner worlds visible. “(p. 72) The influence of Repin as an artist and educator cannot be esteemed highly enough. The long-standing friendship between Leo Tolstoy and the painter Ilya Repin may serve as an example. They agreed on humaneness and their ideals of a just and good social system. In Ilya Repin’s grand picture of “Tolstoy plowing” (1887), the substance of their concept of culture is expressed. By one’s own honest and existential work of tilling the soil the significance of culture as “agricultura” becomes understandable – a multifaceted civilizatory performance in the widest sense. With their work, these artists contributed to a high ideal of education of an entire era. Thus, the most advanced and most viable forces of the Russian art of the 1870s and 1880s were associated in one way or another with the Peredvizhniki.

In the late 1880s a large group of talented young artists joined the “Cooperative for traveling exhibitions”. Apart from the concerns of their teachers new trends and formal varieties of European Art Nouveau took increasingly central stage. More and more issues of the technique of art replaced social and substantive issues. “The crisis of Russian Realism began at the turn of the century. The new social and economic situation, which was caused by the accelerated development of capitalism, also changed the art.” (p. 76) Other values prevailed. The last exhibition of the Cooperative for traveling exhibitions took place after the great October Revolution, in 1922 .

To conclude let us hear once again the art historian Lidija I. Iowlewa: “The pursuit of high m oral and ethical ideals was an essential aspect of Russian Realism, as indeed of the whole Russian 19th century culture. To realize this way of life, the rejection of the existing world order and, primarily, the social structure of society, the steadfast faith in man and the power of his mind and spirit, the confidence in the possibilities of a just and social life and the ability of the Russian national character – all this had inspired the work of the Peredvizhniki in the best years of their interaction and was expressed in all their work, regardless of whether it was about moral images, historical paintings, landscapes or battle scenes.”

Rethinking this major historical development, the great cultural power and the ethics and morals of the Peredvizhniki are certainly worthwhile for society today and for the peaceful accomplishment of the tasks of the coming generations. •

1 Russian Painting in the 19th century (Kunst-haus Zurich, 3 June to 30 July 1989)