Yemen

Yemen

Human Rights desaster and destruction of World Cultural Heritage

by Georg Wagner

In Yemen a merciless war is waged. For six months now, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States have been bombing the poorest country in the Arab world back into the Stone Age. Officially they claim to want to help President Hadi to re-gain control of the whole of Yemen and to contain Iran, whose participation in the Houthi rebellion, however, is nothing but a fantasy. Saudi warplanes have been deployed without any regard to the protection of the civilian population in Yemen. The bombings look more like a targeted massacre of Shiite Huthi than a sophisticated (well thought-out) military operation. Is Saudi Arabia performing a genocide against people of a religious deviation under the guise of a military operation?

More than 5,000 people have died, mostly civilians. More than 25,000 were injured, including thousands of children. 21 of nearly 26 million Yemenis depend on relief supplies, 6.5 million suffer from acute hunger, more than 2 million children are threatened by malnutrition.

The oldest cultural treasures of the Arabian Peninsula – significant parts of the World Cultural Heritage – are being destroyed.

The outcry of the world fails to materialize. In the light of the refugee catastrophe in Syria, currently dominating the media, the silence can only be described as hypocritical. And the United States are supporting the aggression of Saudi Arabia. In this war, the principle of international law, the responsibility to protect, is turned upside down. This principle should facilitate the intervention of the international community to prevent crimes against the civilian population. But this time the “official government” of Yemen (read President Hadi) has his own country bombarded from his exile.

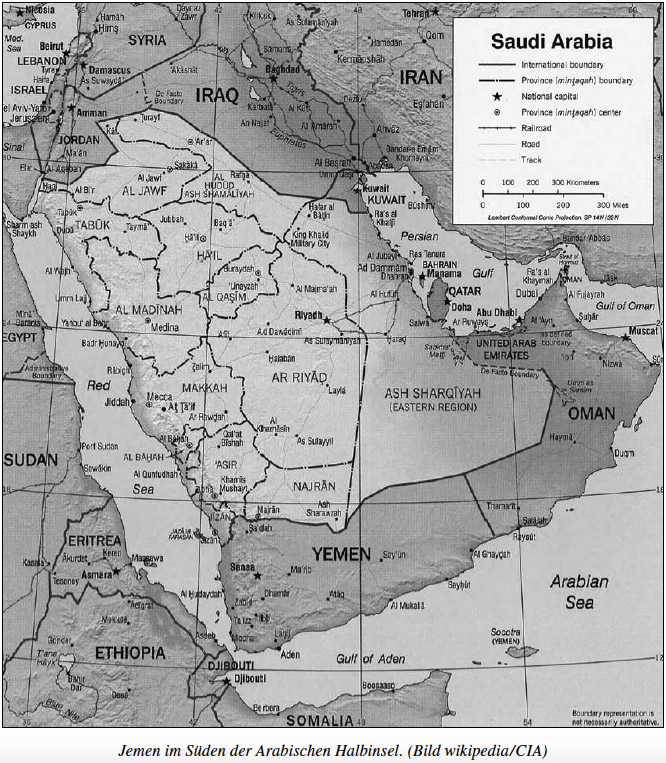

Modern Yemen covers 530,000 square kilometers in the south of the Arabian Peninsula, about 1½ times as large as Germany. It is an Arab country, Islam is the state religion and according to Article 3 of the Constitution the basis of its jurisprudence is the Sharia. The capital San’a is situated at an altitude of 2,300 m above sea level. Her magnificent old city is a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage Site. Other important cities are Aden, Ta’izz, Hudayda and Mukalla.

Yemen has more than 25 million inhabitants and is – other than its neighbors – a densely populated country. With a fertility rate of 6 children per woman in 2009, the population is growing rapidly and is expected to have doubled in 2030. Yemen is one of the poorest Arab countries. 42% of the population live below the poverty level. Yemen ranks 154th out of 177 countries on the Human Development Index (HDI). The HPI-1 value (Human Poverty Inicator for developing countries) for Yemen, 40.67, ranks 76th among 102 developing countries.

Yemen is bordered by Saudi Arabia to the north, and the Sultanate of Oman to the east, the Red Sea to the west, the Gulf of Aden and Arabian Sea, a sea bordering the Indian Ocean, to the south. On the African coast are Eritrea, Djibouti and Somalia on the Horn of Africa facing Yemen.

The inhabitants of the mountains to the north are Za’idi Shiites, the residents of the coastal plain in the south and in the eastern part of the country are Shafi’i Sunnis. Most Yemenis are employed in agriculture. 70% of the population live in villages. Agricultural commodities produced in the nation include grain, vegetables, fruits, qat, coffee, cotton, dairy products, fish, livestock (sheep, goats, cattle, camels), and poultry. But the production of the country covers only ¼ of its requirements, therefore, Yemen is dependent on international food aid.

Oil and gas

Compared to its neighbors Yemen possesses only small oil and gas deposits. Currently, reserves are limited to deposits in Mar’ib, Shabwa and Hadramaut. New natural gas deposits are expected among others in the area that came to Yemen by the redefinition of the border between Saudi Arabia and Yemen. However, considerable investment with uncertain profitability would be required, as in the region Iran and the United Arab Emirates are already producing significant amounts of LNG.

Several oil companies are interested in Yemen, Total of France, Hunt Oil and Exxon of the United States and Kyong of South Korea.

In 2010, the LNG terminal in Balhaf became operative. Income from the oil and gas production generated 70 to 75 percent of government revenue, 25 percent of the GDP and about 90 percent of exports.

The drug Qat

Qat is popular in Yemen, its cultivation consumes much of the country’s agricultural resources. The freshly picked leaves are chewed. In the afternoon, the Yemenis meet for jointly chewing qat and discussing. This is part of Yemeni culture and a social custom. Qat consumption induces mild euphoria and excitement, suppresses the feeling of hunger, but may also lead to anxiety and hallucinations. Consumption of Qat has increased greatly in recent years, the cultivation is paying off, nearly 15% of the population live on it. However, the cultivation of Qat consumes 30% of the arable land, and almost 80% of the countries water supply goes into irrigation, whereby the cultivation of cereals and coffee is affected. And by the strong increase in consuming Qat the economic activity in the country is dropping. Chewing Qat also leads to health problems, since the Qat trees have been treated with pesticides.

Gate of Tears

Its location on the Red Sea gave Yemen a significant role for trade, and since the completion of the Suez Canal in the 19th century for the control of maritime shipping. One of the world’s major shipping lane passes the strait Bab al-Mandeb, the Gate of Tears.

An estimated 3.8 million bbl/d of crude oil and refined petroleum products flow through this waterway toward Europe, the United States, and Asia. Its strategic location could provide Yemen a with security guarantee, but this is not so. From here it is only 15 nautical miles to the coast of Africa; Yemen is situated opposite of Somalia, a country having been warring for 20 years and creating uncountable refugees. According to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees 170,000 refugees live in Yemen, according to the government in San’a 700,000 Somalis live in Yemen. Although the country has ratified the Geneva Convention, the high number of refugees affects its labor market, its health care, and national security. Lack of stability in Somalia leads not only to a high amount of refugees, but also to increased piracy in the Gulf of Aden.

Arabia Felix – Happy Arabia

In ancient times, the part of the Arabian Peninsula that is today called Yemen, was called Arabia Felix, Happy Arabia, due to the mild climate and the fertility of the plateaus, watered by monsoon rains. Twice a year the wadis, i.e. dry riverbeds, became raging rivers. Oases emerged, were people settled in the course of time, and practiced agriculture. Since the 1st century BC they built dikes to protect their fields against flooding. They also developed a system of irrigation for the cultivation of coconut and date palms, vegetables, and trees for extraction of aromatic resins, frankincense and myrrh.

Since ancient times, people in Arabia Felix were sedentary farmers and not Bedouins. The tribe ruled over its territory, protected the common land, the streets and the markets. A code of honor existed for all members of the tribe and since there were often conflicts, the peasants were also warriors. Even today, men never part of their Jambiya, a belt worn curved dagger and a symbol for the honor of the tribe.

The ancient kingdoms in Yemen

From the emerging oases small kingdoms developed. Some of these are lesser-known, others are world famous as Hadramaut and Saba.

In the 3rd and 6th centuries of our era the Ethiopians invaded this territory before the Persian Sassanids expelled the Ethiopians at the end of the 6th century.

The emergence of Islam in the 7th century was a turning point. From 661 Yemen belonged to the caliphate of the Umayyads. Starting out from Mecca and Medina the Arabian Peninsula was gradually united. Incidentally, the Arab Word Yamin means right, as the south is on the right, when viewed from Mecca towards sunrise. After several 100 years of Muslim rule, the Yemeni tribes gradually gained back their independence.

Since the 9th century various dynasties dominated the country. The most significant was the dynasty of Za’idites who founded an Imamat in 901. The Za’idites are a subgroup of the Shiites; they ruled until 1962 on the high plains of the north. Their independence was favored by an economic boom, because the growing importance of the sea route for the east-west trade from India to Egypt via Yemen.

Yemen and colonisation

After the Ottomans had conquered Syria and Egypt in 1517, Yemen had been under their influence ever since 1538. Aden was expanded to an Ottoman naval base. San’a was conquered in 1546, and in 1552, the Imam of the Za’idites submitted to the Ottomans. In the late 16th century Za’iditi troops, composed mainly of tribal warriors, forced the Ottomans to evacuate the country and after fierce fighting the last Ottoman troops withdrew from Yemen in 1635.

Beginning with the age of discovery Portuguese sailors reached the Yemeni coast and founded a trade settlement on the island of Socotra in the 16th century.

In the 19th century the British due to their presence in India began to seek new shipping lanes on their way to England. So, in 1839 Aden came under British rule. The United Kindom controlled the strait Bab el-Mandeb in the south of the Arabian Peninsula and the coast of Somalia. With the opening of the Suez Canal end of the 19th century the strategic importance of Aden ecame even clearer.

In 1872, the Ottomans conquered the seaport city Hudayda, by which they again controlled the north of the country, as they did before in the 16th century. Thus the colonization by the European powers was one reason for the division of the country, because in 1905 the Ottoman and British Empire divided the country among themselves on the basis of several bilateral agreements. The North came under Ottoman administration, even if the tribes still adhered to the rule of the Za’idi Imam.

The British Colony of Aden port

On the southern side lay the British Colony of Aden port and the two protectorates Aden and East-West-Aden; all three areas later were joined to form South Yemen. For a long time two Yemeni States existed, on the one hand based on religious division, on the other hand based on the British-Turkish colonisation. The North was shaped by the presence of the Ottomans, the south remained under British rule until 1967. 1919, i. e. after the World War I, the Ottoman Empire collapsed and the north of Yemen became independent under the Imam Yahya Muhammad Hamid ed-Din, the head of the Za’idi dynasty. He led a guerrilla war against the British protectorate and at the same time he defended the country against Ibn Saud’s conquest of the Arabian Peninsula.

The Treaty of Taif

Finally in 1934, Saudis and Za’idites reached an agreement, the Treaty of Taif. By it Saudi Arabia was granted a dominion over the Yemeni provinces Asir, Nairan and Jessan. The western part of the border was defined, i. e. the part from the Red Sea to the Jebel at-Thar. Further east they failed to agree on a border demarcation. In 1935, Saudi Arabia insisted on the so-called Hamza line, not recognized by Yemen. The border demarcation was not clearly established until in June 2000.

The Yemen Arab Republic in the north

In 1962, the rule of the Za’iditi Imams was overthrown by a military coup and North Yemen became the Yemen Arab Republic with San’a being its capital. Immediately a civil war broke out between the royalists and the putschists. The rebels were supported by Egypt under Nasser with 70,000 soldiers, while the royalists were supported by Saudi Arabia and Jordan. The war lasted until 1967, after the last attempt of the royalists to take San’a, the parties sought a peaceful solution and in 1970, Saudi Arabia finally recognized the Yemen Arab Republic.

The People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen in the south

At about the same time in the south Britain had to leave the country in 1967, forced by protests against the British presence. In 1970, the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen was formed with Aden as its capital. A Marxist Liberation Front seized power and established relations with the Soviet Union. Socotra and Aden were Soviet military bases. And on the other hand North Yemen was – in the context of the Cold War – an ally of the United States. Of course, the end of the Cold War favored the rapprochement between the two countries. With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, South Yemen lost its major donor. So it was mainly the south wanting the union with North Yemen to jointly exploit the oil fields. Saudi Arabia was rather suspicious of these plans. It preferred two weak Yemeni states to a potentially stronger and more populous United Yemen.

Unification of Yemen

The state, calling itself the Republic of Yemen, has existed since May 1990, i.e. since the unification of the more conservative and traditionalist Arab Republic Yemen in the north and the Marxist ruled People’s Democratic Republic in the south.

In the course of this association several border disputes were settled, first of all between Yemen and Oman. There, the border had been set by the British colonial power. The exact border between the two countries was set in 1992, without any major problems, although Yemen forfeited a small part of its territory.

Between Yemen and Saudi Arabia, the negotiations were difficult. Only in May 2000, both countries agreed with each other. The Treaty of Jeddah made the triangle disappear along the Hamza-line, which penetrated into Yemen. Thus, the territory of Yemen increased significantly, namely by 37,000 km² which is about the size of Belgium.

Yemen and the Gulf War

In the Gulf War of 1990–1991, Yemen decided to support Iraq in order to distance itself from Saudi Arabia, which in turn supported the United States and Kuwait. This had serious consequences. Saudi Arabia immediately expelled 800,000 Yemeni workers, and the other Gulf monarchies stopped any economic and financial help for Yemen. The disastrous economic problems and the tensions between the former leaders of the North and the South finally led to the outbreak of a civil war in 1994 and the attempt of South Yemen to separate. There was fierce fighting in Aden and Mukalla. But the segregation failed, and the economic situation was even worse afterwards than before.

Since then Yemen has actually been mentioned in the headline solely because of tourist kidnapping. The most dramatic representations in the local press ignore that the Yemeni society functions by different rules than ours does. A unitary state is without any role model in the history of Yemen. In a country where the farmland and pastures are scarce, the tribal community alone offered the people a chance of survival. Against this background, conflicts of interest between the autocratic Saleh administration and the autonomous tribal leaders are inevitable. In the fight against discrimination and in order to enforce their claims (for example, construction of roads or health centers), the tribes operate by kidnappings. Victims may be foreigners, because they are considered guests of the government according to customary law. At the same time, this very law respects the life and limb of the hostages.

Yemen and the fight against terror

In the late 90s there were several attacks in the context of international terrorism. In Yemen, al-Qaeda had been active since the early 2000s.

On 12 October 2000 al-Qaeda committed a suicide bombing on the US destroyer Cole in the port of Aden. 17 US soldiers lost their lives in the explosion. After the attacks of September 11, the United States suspected Yemen, to provide shelter for al-Qaeda terrorists. The Yemeni origin of the bin Laden family and the arrest of dozens of Yemeni fighters in Afghanistan seemed to confirm them in their suspicions.

The year 2008 saw an attack on the American embassy and on foreign tourists in several cases. This put Yemen under increasing international pressure to take action against al-Qaeda. After the Saudi and Yemeni branch of al-Qaeda had merged in January 2009 under the name of AQAP, the government in Sana’a decided to join in the fight against terrorism. The kidnappings have since then been referred to as terrorist actions, which the army responded to, often with bloody consequences.

This new attitude was a twofold advantage for the government in Sana’a: It provided an opportunity to consolidate its authority in those tribal areas that so far had only insufficiently be controlled. Especially in the regions of Shabwa, Jawf and Mar’ib. In addition, this prevented Yemen from being placed on the list of rogue states by Washington.

Meanwhile, Washington and Sana’a are working together closely in the military sector. The US send military advisers to train the Yemeni special forces. Since 2004, the FBI disposes of a permanent branch in Sana’a and the border in the great Arabian desert is monitored by drones. These are controlled from the US base in Djibouti.

The Houthi conflict

In June 2004, the Houthi conflict began as an uprising launched by the anti-government cleric Hussein Badreddin al-Houthi against the Yemeni government under Saleh. Hussein al-Houthi was killed in September 2004 after three months of rebellion. In 2005, President Saleh granted amnesty for the imprisoned followers (more than 600) of the Zaidi preacher, but later there were new arrests and convictions, even capital punishment.

The Zaidi have been living in Yemen for over a thousand years. Zaidi imams ruled until the revolution 1962 over the northern part of Yemen. In the 1990s, the Zaidi felt increasingly marginalized in the face of the growing influence of Sunni fundamentalists. Added to this was the political and economic neglect of the province of Sa’ada after the civil war of the 60s by the Yemeni government, whose efforts for nation-building was limited to the financial patronage of tribal leaders, accompanied by an unequal distribution of wealth and resources.

The Houthi protest culminated in the armed conflict with the Yemeni army in 2004. The then President Saleh – himself being a Zaidi – branded the Houthi as “terrorists” and accused Iran to fund the insurgency. The Houthi fight al-Qaeda and Islamists, but Israel and America consider them as political enemies. From 2004 to 2011 the Yemeni government waged six wars against the Houthi movement. By 2010, thousands had been killed, hundreds of thousands had been forced to flee.

In addition, there is the antagonism between the regional superpowers Saudi Arabia and Iran, the so-called fight against terrorism and its impact on the internal politics of Yemen, which led to an increase in anti-Americanism. Then there is the resistance against the intended fortification of the borders with Saudi Arabia, which threatened to cut off the inhabitants from their traditional trade and supply lines. In 2008, the government claimed that the Houthi wanted to overthrow the government and introduce Shi’ite religious law and accused Iran of leading and financing the uprising.

In 2009, there was a new offensive against the rebels in the province of Zaida. 100,000 people fled the fighting. Along the border there were clashes between the northern rebels and Saudi security forces. The Saudis then launched an anti-Houthi offensive which the United States participated in with 28 attacks of their air force. After a cease-fire in early 2010 the fighting flared up again. Fighting took place in the districts of Zaida, Haddsha, Amran and Al-Jawf and the Saudi province of Jizan.

After 2010 the Houthi succeeded in establishing alliances and marriages of convenience with local tribes. Many tribal leaders, disillusioned by the central government, joined the Houthi. Both the Houthi as well as the government at that time promoted the outbreak of old tribal feuds to mobilize the tribes for their own respective positions.

When the Arab Spring of 2011 seized Yemen, the Houthi movement joined the protest and President Saleh was forced out of office. On 21 February 2012 presidential elections were held. The only candidate was the Vice-President Abed Rabbo Mansur Hadi, who was to take over the presidency for two years to initiate a constitutional reform. Thereafter, re-elections were to take place.

But the security situation and the economic situation of the already poorest country of the Arabian Peninsula continued to deteriorate and support for the new government of President Hadi waned. Al-Qaeda increasingly gained power and got much of South Yemen under control.

March 2013: A national dialogue was initiated to enable the transition to democracy. Several political groups, including the Houthi, were working on a new constitution. When fighting between al-Qaeda groups and the Houthi occurred in the north, the Houthi dissociated from the outcome of the conference in early 2014.

In September 2014, 30,000 Houthi followers besieged the capital Sana’a and took over important government buildings. In October, the rebels forced a government reshuffle of President Hadi, and they advanced in the east and south of the country.

In January 2015, the Houthi surrounded the presidential palace in Sana’a with tanks. Hadi and several government members were placed under house arrest, the president offered his resignation.

In February 2015, Hadi fled to the southern Yemeni city of Aden and made its refuge the new capital. The rebels began their march on Aden.

End of March 2015, the Houthi conquered the last military bases before Aden, using the help of ex-President Saleh’s followers. Hadi fled to Riyadh in Saudi Arabia and asked his Arab neighbors for intervention.

In March 2015, a military alliance, established by Saudi Arabia and consisting of Egypt, the Gulf monarchies and others, started an offensive against the Houthi, logistically supported by the United States, France and Great Britain. •

Bilqis, the Queen of Sheba

According to ancient narrations Bilqis, the Queen of Sheba, lived in fabulous wealth and reigned in a country with flourishing gardens, well smelling frankincense and myrrh. The gigantic dam in Mar’ib belongs to one of the man-made wonders of the world till today. The early Arab empire of Sheba existed from the 10th century BC to the 3rd century AD. Signs of this ancient High Culture of South Arabia are the pillars of the temple Bar’an and Adam as well as the remains of the 600 m long and 17 m high dam, whose locks led the precious water from the Wadi Adhana to the fields. The dam held a thousand years. When it disintegrated in 600 BC, a big wave of emigration started from southern Arabia to neighboring areas like the Saudi Arabia of today.

The Incense Road led through Sheba, starting in India and reaching the Mediterranean Sea. Because of this Road caravans with immeasurable wealth reached the country, such as frankincense, gold, myrrh, precious stones, sandalwood and other precious objects. In the Bible, in the Book of Kings, we read: “They came to Jerusalem with a very large escort, with camels, carrying Balsam, a huge amount of gold and precious stones […]”

Frankincense and myrrh were transported by caravans into the entire Mediterranean region, to Egypt, the Levant and the Roman Empire. One also traded with Abyssinia, Persia and India. Sana‘a was a veritable trade center with an astonishing cityscape: the narrow high-rise buildings, which seem like early skyscrapers, are a World Cultural Heritage.

After the tradewinds had been discovered, the overland trade of the caravans didn’t have worth anymore. Sheba‘s wealth was scattered.

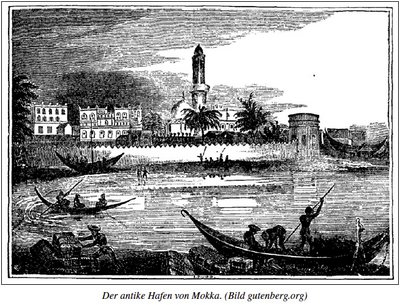

Mocha – the town where mocha comes from

Today everybody knows the word of Mocha or has heard it as at least once. But what exactly is mocha? A variant of cappuccino with chocolate? A certain brand of coffee beans? A traditional way of preparation which has its origin in the Turkish or Arabian region? In fact all this is correct, as there exists hardly any term used in this manifold ways. Beside the range of meanings there are still numerous spellings. Be it mocha, Mocha, or mokha, they have all got the same ethymological origin – the town of Mocha (in Arabian al-Mucha). It is situated in the southwest of Yemen directly on the coast of the Red Sea, but 12 metres above sea level, and it looks back upon a long and above all a changing history. The origins of the town are presumably in the ancient harbour town of Muza, supposed to have been in the same spot or at least nearby. Mocha was not only the most important trading centre for coffee, it was also one of the most significant trade centres of the whole region. It was part of the so-called Silk Road, the most important trading road at that time.

Mocha played a decisive role in world trade above all concerning coffee. At first coffee beans grew in Ethiopia, later, however, they used to be cultivated in Yemen also, and for a long time, they were exported exclusively to the world then known. There was a demand rather soon because the interest in enjoying coffee was spreading like a virus from the Arabic region to Europe. In the middle of the 16th century the first coffee house was opened in what is Istanbul today, and some 100 years later, there followed coffee houses in London, Paris, Amsterdam and Hamburg. During that time, Mocha was keen on serving the demand, but they took care of preserving the monopoly in coffee. There was usually water poured over the mocha beans in order to prevent them form germing.

At the apogée there existed a law prescribing to any ship that landed in the harbour of Mocha – whoever was underway from the Arabic to the Red Sea or reverse had to pay the obligatory taxes for the goods that were carried along. From the 15th to the early 18th century, Mocha was not only the most important commercial centre for coffee, it was also one of the most significant trade centres of the whole region. By former standards Mocha with up to 30,000 inhabitants was a megapolis and you could have met traders from all over the world there. Britons, Dutch, French and Danish people maintained warehouses/storehouses and their own factories in order to quench the thirst for coffee in their home countries. But like many things in life, the history of the success of mocha was evanescent. The Europeans succeeded in spreading the coffee plants and to cultivate them in their colonies. In the course of 18th century coffee came to Indonesia, to Surinam, to Brazil, and to the Carribean. Here the conditions for cultivating coffee were scarcely worse and thus the coffee monopoly became a page in the history book. The decline of the harbour town had started.

Today’s Mocha is almost meaningless and has just around 10,000 inhabitants. The old coffee warehouses and trading houses decay, and the port seems doomed. In 2013, the former world leader Yemen exported nearly 20,000 tons of coffee. What sounds like a huge amount, is put into perspective when looking at the competitors from other continents. Brazil, for example has harvested almost 3,000,000 tons in the same period, and even countries as Burundi, Madagascar and El Salvador are well ahead of Yemen. Nowadays, people in Mocha mainly earn their living on fishing and the marginally existing tourism. And yet, Mocha is on everyone’s lips – in sidewalk cafes in Paris as well as at Starbucks in New York City or in a Berlin restaurant.

The Incense Road

The Incense Road from South Arabia to the Mediterranean Sea is one of the oldest trade routes in the world. Here, the incense was transported from its country of origin in Dhofar, today’s Oman, across Yemen, Asir and Hijaz to the Mediterranean port of Gaza and to Damascus. Important trading posts on the caravan route were Shabwa, Sana’a, Medina and Petra.

The development of the Incense Road was only made possible by the domestication of dromedars in the middle of the 2nd millennium BC. Making use of camels as pack animals, the dependence of caravans from the water holes in the desert decreased.

Next to the incense also spices and precious stones from India and Southeast Asia came to Palestine and Syria via camel caravans. At Petra, north of the Gulf of Kaaba, the Incense Road divided into a northern branch ending at Gaza and an eastern one which led to Damascus. According to reports by ancient authors, it took the camel caravans a hundred days to march the 3,400-km-long route between Dhofar and Gaza.

It is likely the Incense Road was used for the first time in the 10th century BC. However, there was an upswing of trade only after the emergence of the South Arabian kingdoms of Saba, Qataban, Hadramaut and Ma’in in the 8th century BC.

Since the 5th century BC, the high demand for incense used in ritual ceremonies in the Mediterranean led to a thriving of the route and the cities and empires that connected them. Around the birth of Christ, the Roman Empire alone is said to have consumed 1,500 tons of the estimated annual production of incense, amounting to 2,500 to 3,000 tons.

The eventual decline of the Incense Road begins with the development of the sea route through the Red Sea. Not only the old caravan route loses its meaning. The ancient Arab kingdoms were gradually losing their economic base as well. In the 3rd century this resulted in the rise of the Himayarites in Yemen. Now, they relied increasingly on agriculture in the climatically favorable mountainous region and on the control of maritime trade.

The triumph of Islam in the 7th century meant another serious setback for the trade route. Although incense continued to be used in Islamic medicine, it did not in the religious sphere of mosques.

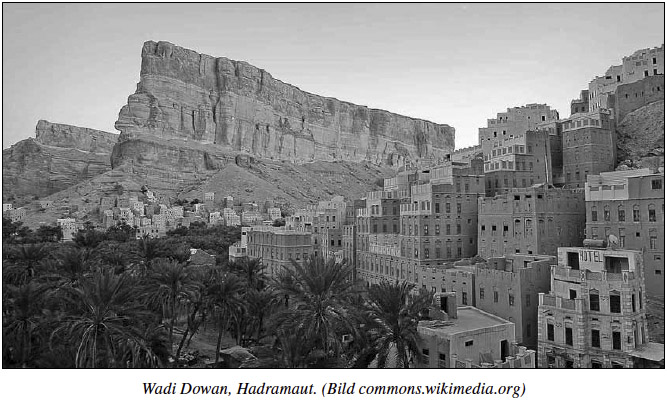

The towns of the Hadramaut

In ancient times, the Hadramaut was called the “Holy Land”. Many graves from pre-Islamic prophets and other saints are reminders of those days. The Wadi Hadramaut that could be reached until the 60s only through the desert Rub al-Khali, Marib and the plateau of al-Mukalla, is a fertile river oasis, surrounded by kilometers of date palm groves and majestic mesas. The three cities of Shibam, Sa’yun and Tarim are located in this cultural landscape.

The Hadramaut was and still is a troubled area. At all times, the Hadrami competed for the little fertile soil of this barren region. They protected their small towns by thick mud walls that no bullit could penetrate, and defended their dwellings by carved loophole windows.

But the Hadrami would have been well protected in their strongholds of clay, if there had not been now and then heavy rains which the walls and houses could not counter at all. Every few years, parts of the settlements are literally washed away by the floods.

People had survived here in the few fertile parts of the Wadi since pre-biblical times. The Hadrami were famous as traders, as they maintained contacts up to Indonesia, India and Africa. Their high, partly whitewashed mud houses reflected their wealth. They often decorated the mostly unadorned facades with elaborately carved and heavily studded doors.

These Hadramaut cities might be described as “World cities of Architecture, because what we find there as healthy power everywhere, sprung from its own soil in unbelievable richness, down there in the Arabian Peninsula, where we previously suspected nothing but desert and bare mountains, surpasses all our expectations.

Sky-scrapers of the desert, at a time when America knew only paltry huts! Each of these cities offers an architectural image of purest content, testifies to an art of building that one would have never imagined the Arab population to be capable of.

The reason for this peculiar design, which actually is not Arabic, is explained by the insecurity of the country. South Arabia is constantly haunted by a predatory war. Bedouins raids are rampant. Each house, each village and each town is a self-contained fortress. And all houses are built of mud.”(cf. Hans Helfritz. Chicago der Wüste. 1935)

If Sana’a is time and again referred to as the Pearl of Arabia, then Shibam earns at least the attribute pearl of the Hadramaut. For centuries, the old trading town was one of the most important caravan bases along the legendary Incense Road with the bizarre landscape of Wadi Hadramaut.

In Shibam there are no real monuments. The city itself is a monument as much as the civilizational achievements of its inhabitants. High-rise buildings without elevators? Far from that. Even in ancient times, cargoes – and presumably people too – were transported via elevators to the upper floors. That worked over a role fortified on the rooftop with appropriate counterweights. In the 3rd or 4th century AD, Shibam was founded as successor to the ancient capital of Shabwa. Under the pressure of semi-nomadic tribes from north of the desert the situation of Shabwa had become untenable then.

In Shibam there are approximately 500 high-rise buildings, most of them are over 30 meters high and have more than 8 floors. Many of these houses are between 200 and 500 years old.

For the construction air-dried bricks of clay mixed with chopped straw were used. As protection against erosion through wind and rain the upper floors were plastered with bright white lime.

In hardly any other city, the traditional Arab life has been preserved as much as it has been in Shibam.