On the death of Professor Dr Dr Siegwart-Horst Günther

When on 18 October 2007, on the occasion of the 10th award ceremony of the “Nuclear-Free Future Award” this honour in the category “Enlightenment” was awarded to Professor Dr Siegwart-Horst Günther, he said the following in his speech of thanks:

“When I found out, after the first Gulf War of 1991, that allied troops had employed uranium shells in that war, with all their terrible consequences, I was outraged about this atrocity. War is terrible in itself, but the use of this ammunition and of depleted uranium bombs constitutes a war crime against humanity and earth.”

Already in March 2002, on my first encounter with Professor Günther it had become clear to me what this man has done in terms of education on uranium ammunition and its terrible consequences. He had shown to me pictures of newborns with terrible deformities and explained that the fathers of these children had participated in the heavy tank battle south of Basra in 1991, when the Allies had used more than 320 tons of armour-piercing ammunition of depleted uranium. This monstrosity revealed by Professor Günther would bring him much trouble, especially in the Federal Republic of Germany. In the 1990s, he was virtually discredited and persecuted for this.

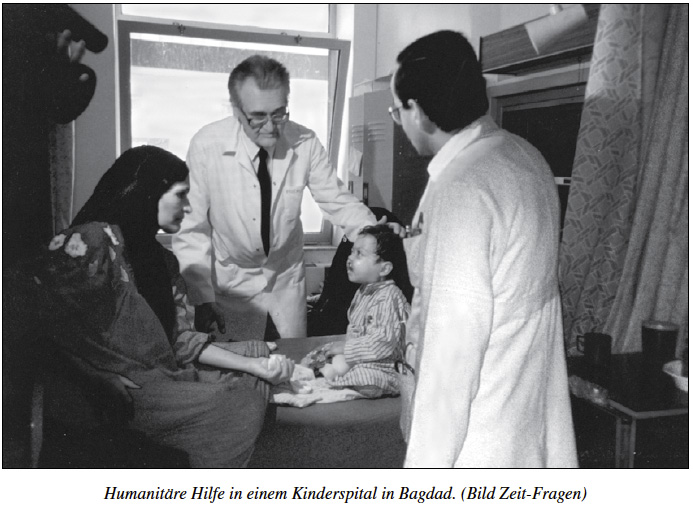

In 2003, while filming with him in Jordan and Iraq, however, I was able to learn how highly respected and widely known abroad he has always been, particularly in the Middle East. At Amman Airport, where passengers had to wait for the visa, he was politely waved from the queue, escorted to a small table, offered a comfortable chair and served tea and biscuits. While we, the ordinary mortals had to stand in line for an hour to get the visas, Professor Günther’s passport had long been provided with the necessary visa by a courteous unbureaucratic official. And later, on welcoming Professor Günther at the Children’s Hospital of Baghdad, he was embraced by the director of the hospital like an old friend. At this, the director was touched to tears by the unexpected meeting.

On a long car ride in Iraq I asked the professor, who had become 79 years in the meantime, why at this age he would go again on such an arduous and dangerous journey. For when in fall of 2003 we entered the Iraq, UN officials and almost all Western embassy employees had long since left the Iraq because of this instable situation. Professor Günther replied cheerfully and relaxed, “You know my young friend, I am a doctor committed to the Hippocratic oath and this oath has no age limit.”

Professor Günther who was born 24 February 1925 in Halle on the Saale refused to be drawn into the crimes of the “Wehrmacht” even as young soldier on the Eastern Front. Later on this took him to the German resistance and, as a consequence, to imprisonment in the Buchenwald concentration camp in the context of the Hitler-assassination attempt of 20 July 1944 shortly before the end of the war.

His name and his findings on the “Gulf War Syndrome” will remain in memory amongst others in the two movies “Der Arzt und die verstrahlten Kinder von Basra (The doctor and the contaminated children of Basra” and “Deadly Dust” (2004 and 2007). Spectacular and unforgotten is the action where he smuggled the remains of uranium ammunition from the Iraqi war zone to Berlin, whereupon he was prosecuted for the “dissemination of radioactive material”. So much for the alleged and still claimed for safety of ammunition.

Professor Günther died in the night of 16 January in Husum. All of us who knew him, bow in reference and awe to this straight-line and truth-seeking physician and scientist. In his spirit, we shall continue working in honouring commemoration. •

(Translation Current Concerns)

“It is good, that you have come to help us”

“As a former employee of Dr Albert Schweitzer I have been working for many years in the context of humanitarian aid programmes in areas of tension and every day I had to see the enormous suffering and death of people, especially children there.

In Kosovo, as well as in the Gulf region new discussions are lately being lead by the UN, but hunger and death continue.

Albert Schweitzer’s speech on receipt of the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo on 4 November 1952 is particularly valuable, especially in these times. At that time he said, ‘The statesmen who were responsible for shaping the world of today through the negotiations which followed each of these two wars found the cards stacked against them. Their aim was not so much to create situations which might give rise to widespread and prosperous development as it was to establish the results of victory on a permanent basis.’

Unfortunately this attitude has not changed to this day.

Albert Schweitzer was convinced that the threat of new wars of extermination could not be banned by international agreement or any institutions, but only by the morally determined attitude of all those responsible.

Many events of recent times show that we are now in a situation in which the ethical and humane attitude does not progress to the same extent as the external power resources do.

The Übermensch [“higer man”] appears to develop more and more into a barbarian.

Albert Schweitzer believed steadfastly that those decisive effects which secure world peace can only develop in the spirit, in the moral attitude of the individual and of nations.” (Preface)

„As a participant of the Second World War, where I had to witness many crimes and was a victim myself, I pursued with growing empathy the crimes of the new wars and its consequences. This was caused not least by my friendship to Albert Schweitzer and our joint activity in the jungle Hospital in Lambarene. Therefore, I will not get tired at this point to call upon all people to maintain peace and provide help where it is needed. In the Gulf region, in the former Yugoslavia, in Africa, in Latin America. And if these thoughts should produce a lasting effect within the reader only, even then the effort would have been worthwhile.“ (Epilogue)

Professor Dr Dr Siegwart-Horst Günther, Hunger und Not der Kinder im Irak. Epilogue, Publishers Zeit-Fragen, Zurich, 2007

* Albert Schweitzer welcomes Siegwart-Horst Günther on his arrival in Lambarene, in 1963.

(Translation Current Concerns)