Water supplies in the Valais in danger The power supply is a joint effort – it is important to take care of them (Part 1)

Water supplies in the Valais in danger

The power supply is a joint effort – it is important to take care of them (Part 1)

by Dr rer publ Werner Wüthrich

Water and the water rights have always played a central role in the Valais. Those who explore the Valais on foot will inevitably come across the irrigation channels in many places. These artfully designed irrigation channels made it possible for the population to live and cultivate the ground high above the valley on the sun-drenched terraces where there is only little water. The “Suonen” (irrigation channels) transport the water from often distant mountain streams – along steep slopes in beautifully constructed mains. They disappear in tunnels and are sometimes hung on vertical walls to direct the water to where it is urgently needed for survival. The cultivated land is especially affected by the drought, because the high ridges retain the rain clouds. In the mountains it rains more often, and huge amounts of water are stored in glaciers. In the valleys, however, the water must be used and distributed judiciously.

The irrigation channels criss-cross the landscape like blood vessels the human body. Finally, the “Rüüsä” (rivulets) take the water of the irrigation channels down to the meadows. The “Schrapfjini” (distributors) distribute the precious liquid on the cultivated land in fine basins and branches. This centuries-old irrigation system is still used today and should be protected as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

The irrigation channels are the population’s joint effort. In spring, the damage of winter must be repaired. Residents meet in “community work” which was often dangerous in former times. The water rights are cooperatively supervised by the communes. Everyone knows when and how long he can direct the water onto his fields. An arbitration court settles the disputes. Today, new materials, pipes and new techniques have made the work easier and less dangerous. Many of the artistically constructed irrigation channels, which have long been working well, are still in operation and direct their water onto the fields and pastures day by day. The irrigation channels have become the source of life for the Valais mountain villages – until today.

Hydro power makes Switzerland more independent

About a hundred years ago the water in the Valais had another very different meaning. The Industrial Revolution had changed Switzerland’s appearance significantly in the 19th century. The energy problem had to be solved. The factories were working mostly with coal – and coal had to be imported at a one-hundred-percent level. During the First and Second World Wars, people found out that this dependence could definitely reach alarming levels. Electricity could replace coal and later also partly the oil. It could be generated by turbines that were powered by water. The railways, too, were working on coal, and it was reasonable to electrify them as well. In 1917, the Swiss Federal Railways decided to electrify the operationing of the railway. The Gotthard route was one of the first tracks that benefited from this innovation. In 1939, the National Exhibition Switzerland proudly presented the most powerful electric locomotive in the world which was able to pull eleven fully loaded wagons along the slopes and bends of the Gotthard route. Many industrial plants quickly switched to the new form of energy. The electrification of the railway, industry and households was to become a major task for the whole country and was one of the conditions for Switzerland’s impressive industrial development. Already in the last decade of the 19th century, the first river power stations were built. Soon the first reservoirs were added, which collected water from the glaciers. This development reached its peak in the 1950s and 60s, with the construction of numerous large-scale systems.

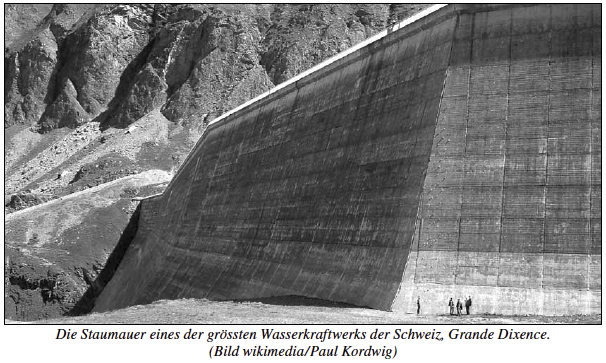

The construction of the Grande Dixence dam is to be described as an example. The 2012 deceased Hans Wyer, a longtime State Councillor in the Canton of Valais and President of the CVP Switzerland, published a large, comprehensive work entitled “The use of water power in Valais”. In it he describes the events of that time in great detail.

Grande Dixence – a project of the century

In 1950, construction began in the Vallée des Dix. The plan was bold. The concept was visionary and beat everything ever seen before in terms of size and estimated sums. The 285-meter-high dam – until recently, the highest dam in the world – is 200 meters thick at its foot. It collects water from 35 glaciers and countless waterways. 80 water intakes and 100 kilometers of tunnels take the precious liquid even into remote regions such as Zermatt and direct it into the artificial lake, there. In 1960, after a construction period of ten years, the dam was finished. A further five years were spent on the work until the electricity production could be fully incorporated. In recent years, the facilities were renovated and expanded so that the electricity production was almost doubled.

About 3,000 people were involved in this project, often working under difficult conditions. But it was a great adventure. It was sometimes cold and stormy, and the great height caused the workers and engineers some trouble. Initially they worked almost under war conditions. However, the working conditions soon improved. By the end of the 1950s, the shifts were reduced to 8 hours and they did no longer have to work on weekends. In the valley a barrack village was built for the workers with shops, a restaurant, a kiosk, a cinema and a sports field, were football matches against teams from the surrounding villages took place. During leisure-time, the workers met in gymnastics clubs or choirs. A bank branch helped them to transfer their salary to their families, especially in Italy. Life was supposed to proceed as normal as possible, which it did successfully, as witnesses reported.

Here are two excerpts from the above-mentioned work of Hans Wyer:

- “Many mountain farmers [...] and workers who came from all directions, spent several years in the strange and hostile environment of mountains wilds. They hollowed out the rock, drove tunnels and shafts and blasted caverns: the underground control rooms. They put their health at risk and often their lives – fatal accidents were nothing out of the ordinary.”

- “The mountain farmers welcomed the establishment of the construction site as a godsend. Finally the long awaited opportunities to earn money were there. They accepted the job straightaway because they did not have to leave their village and were able to continue their homestead. The burden of poverty that before had pushed them to the ground, became easier.”

Such descriptions are representative of many building sites in the Alps, where people worked on similar projects. A large number of dams was built at that time. Switzerland tried as soon as possible to refrain from coal as an energy source, which had brought the country into dangerous dependence on Nazi Germany in World War II. However, Grande Dixence was the biggest project by far. A black day for Switzerland was the 30th August 1965. Several hundred workers worked in the Saas Valley – near the Grande Dixence – on the dam of Mattmark, when a glacier crash of the Allalin Glacier buried 88 construction workers under half a million cubic meters of ice. A memorial commemorates this probably biggest disaster in Alpine tunnel and power plant construction.

Careful handling of nature is now playing a more and more important role. In Valais, environmental organizations, the Cantonal Department of Energy and power plant companies confer at a round table to solve the problem of residual water by mutual agreement. Drained and very little water-bearing streams will soon be an issue of the past. (“Walliser Bote”, dated 6.6.2013) Recently, the Electricity Company of Canton Valais announced to dam the Rotten (the Rhone) in its upper reaches to run a power plant. The project comprises part of the river water at Gletsch below the Rhone glacier, leading it through a gradient of 280 meters to Oberwald. Pipes, turbines and control rooms are created exclusively underground. The plant is intended to supply 9,000 households with electricity. The output is just under a tenth of the Grande Dixence. – But this is only one side. At the same time the Rhone, which is still heavily built up, is being renatured. It should meander again in the large protected floodplain between Gletsch and Oberwald, i.e. it should seek its course freely again. Thus, this nature reserve is upgraded. (“Walliser Bote”, dated 23.5.2013)

Who owns the Grand Dixence?

The Grande Dixence SA, based in Sion is now the owner of the largest power plant in Switzerland. It is now the market leader for electricity from hydro power in Switzerland and in Europe. The Grande Dixence SA in turn belongs to Alpiq by 60%, a company formed in 2008 after the merger of Atel (Aare-Tessin AG) and the EOS (Energie Ouest Suisse). The Axpo (formerly Nordostschweizerische Kraftwerke NOK), BKW (Berner Kraftwerke), IWB (Industrielle Werke Basel) each hold a

13 1/3 per cent share. 17 cantons are involved directly or indirectly. The Valais, however, is itself hardly involved. For two years, a man from Upper Valais has been the director of this company for the first time. Alpiq and BKW are public limited companies whose shares are traded at the stock exchange. However, more than 80 percent belong to the public sector. Axpo is wholly-owned by the Northeast Swiss cantons. Therefore the Grande Dixence belongs almost entirely to some cantons and large cities, especially in German and French speaking Switzerland.

The Grande Dixence is just one of many power plants. Altogether, there are about 50 larger power plants in Valais, including three of the four largest reservoirs in Switzerland. They supply a third of the electricity in the country. 80 percent of the Valais hydro power is, however, predominantly in “foreign” ownership. According to experts’ report only about 170 million Swiss francs flow into public funds of the Valais nowadays.

Escheat is imminent

The sovereignty over the waters of the Rhone is with the canton. The communes are responsible for the tributaries that flow into the main river. This division gives the mountain communes in the side valleys a strong position, because almost all power plants are located on their territory. On what terms have the communes given away their water right concessions?

The big electricity companies in Switzerland use the local water power at an annual water interest. However, the Welsh were clever people. In the first half of the 20th century they tied the use of hydro power to an important clause. After the expiration of the 80-year concession period the so-called escheat comes to pass. This means that a large part of the power plants (80 percent) fall back without compensation to the commune that once issued the license. In practice this means: The commune, in most cases some mountain communities, can take back the “wet systems” of a power plant, i.e. the dam, the pressure pipes and turbines as their property at no cost. At the same time, the communes can purchase the “dry parts”, i.e. the electrical equipment for a reasonable compensation from the previous operator. Plants worth many billions of francs might change hands that way. The Valais media speak of assets totaling about 20 billion francs. Small mountain communes in the valleys of the Rhone profit mostly, which is, however, hotly debated in many communes.

The water rights treaties that the communes and the canton of Valais once settled with the big electricity companies in Switzerland look similar. They also provide that the equipment “escheats” at end of the concession period.

In the first half of the 20th century, the use of hydro power with large storage facilities was as new as the large wind farms are today. No one really knew whether the enormous efforts would “pay off” and would be of long-term use. No one could say whether it would be possible to operate the industry and railways throughout Switzerland efficiently and cost-effectively with electricity. Nobody knew whether the expensive equipment would one day be standing about uselessly in the countryside. – The “escheat” in the treaties of the Valais communes was a kind of insurance for an uncertain future. For the current generation the escheat is a piece of good fortune. They can benefit from the foresight and caution of their grandparents and great-grandparents – all the more so because the hydroelectric power is considered more and more valuable in today’s energy debate.

How to proceed?

As an extreme example, the communes Eisten and Zwischbergen are often covered by the Valais media. In case of an escheat of the power plants Mattmark and Ackersand I they would obtain assets per inhabitant of approximately 1.5 million francs. There has already been a recent example: the SBB recently purchased the escheat rights from six communes in the Trient valley and paid 343 million francs for the license renewal of Barberine power plant. Of these, the commune Finhaut with its 367 inhabitants obtained 112 million francs. Although the commune’s council wanted to realize expensive tourist plans with the money, the voters showed once again the prudence that is on the agenda in direct democratically organized Swiss communes: They rejected the project in the communal assembly.

There is also another example: In 1945, the commune of Bagnes voluntarily renounced the escheat law in its concession contract for the Drances de Bagnes.

In case the escheat will be exercised completely and according to contracts in the near future, the great power plant operators in Switzerland will not only lose the title to the equipment, but also the right to use the water with which they produce the electricity. From 2030 on the big power plants – including the Grande Dixence – will start to escheat. About 80 percent of the plants will become the property of communes without any compensation. In reality, this will have to be settled much earlier. Today‘s operators have – understandably – announced that they will only invest and repair the equipment, if they can be sure to become involved in the Valais’ electricity production in the future, as well.

Jürg Aeberhard, head of hydraulic production at Alpiq, visited the Valais a few years ago and remarked, thereby displaying a lowlander’s not very insightful view: “The communes are the happy winners in escheat cases.” They did, however, not own the prerequisites to successfully operate a large power plant, he said. Neither would they be financially capable of responding to all kinds of disturbances, industrial accidents and replacement investments. Moreover, they would also have to have access to the European electricity market. Aeberhard then suggested finding a – as he called it “good Swiss compromise”. Today’s operators and communes might share “fifty-fifty”. (“Walliser Bote”, dated 26.3.2011) Understandably this proposal met with little positive response in the Valais. The well-known journalist Luzius Theler wrote in “Walliser Bote” of 29.3.2011: “Alpiq wants to claim half of the escheat values for power plant operators. This is either naive or blatant – or both.”

Neither did Councillor Jean-Michel Cina, a member of the Valais government, accept Aeberhard‘s arguments: “What the Central Plateau cantons can do, the Valais can also do: Why should we not also establish a power company, ourselves”, he asked. Zurich and Geneva were the financial centers, Biel was the competence center of the watch industry. The Valais could become the energy canton, a center of excellence for hydro power. The first steps had already been taken. Skilled jobs would be created. By 2015, the ETH Lausanne will build an institute with eleven professorial chairs in Sion, capital of the canton of Valais. Seven of these are reserved for the energy sector.

Cina continued that it was wrong to disqualify the mountain cantons from managing the power stations themselves. There were also no plans “to oust the previous operators totally”. The escheats offer the chance to directly take responsibility and achieve more income in addition to the water interests. “Will we soon be water sheikhs?”, asks Jean-Michel Cina. “I would not mind if the canton of Valais became so rich that it might assign compensation to some other cantons according to the fiscal equalisation scheme. Today it is still the other way round.”

(www.1815.ch/wallis/aktuell/sind-wir-schon-bald-wasser-scheichs-49820.html)

Who will reign in the water castle in future?

The following solutions are favoured:

1. The communes cash the bills and renounce to acquire and run the power plants. They grant a concession to today’s operators like Alpiq, Axpo or BKW.

2. The commonwealth, i.e. the benefited communes or cantons transfer the power plant facilities that have become their property into a new company. The former operation companies would contribute the “dry parts” (which means electro-technical installations), their know-how, their technical knowledge and their commercial relationships with the European world of power. Both, Valais and Alpiq, BKW and Axpo, would furthermore operate in a joint venture.

Controversial is the percentage of communal participation in the future company. Nowadays the big companies like Alpiq, BKW and Axpo command 80% of the total power generation. This is to be changed. Valais wants to participate directly and targets a percentage of 60% – as against 20% today after the “Heimfall”. “Valais must have the say again”, says state Councillor Jean-Michel Cina. Power generation would become a joint endeavour in which local inhabitants would act as “head of the household”.

With this procedure, however, not all the problems are solved yet. The Valais itself has to work out just solutions but must also consider the interests of whole Switzerland. The wealth, which the small mountain communes are now facing, raises desires. Just one third of the communes in the Valais profit from it. The Upper Valais, where only just one fourth of the population lives, owns half of the water power. Currently this is compensated by transferring the cantonal water power taxation of 60% of the communal water-costs to the communes.”Heimfall” and water right concessions are to be newly regulated. Former Councillor of States (CVP) Rolf Escher suggests: The licensing authorities are to benefit from the reversion by one half and both canton and communes by a fourth each.

On 17 January 2013, communes of Upper Valais informed about the decisions by an overwhelming majority that they wanted to cooperate with a strong partner from the electricity industry who would hold 40% of a joint company. The licensing authorities are to hold 30% and both not licensing authorities and the Canton of Valais each 15%. The political left prefer a solution in which all power plants are run by a single cantonal company. (“Walliser Bote” of 19 January 2013)

Among the cantons there are open questions due to waterpower as well that must be solved at a federal level. Currently the mountain cantons negotiate with some cantons of the Swiss central plateau in which the power plants companies are located. The profits those companies generate by water are to be taxed in the regions where they occur. Today the big companies generate profits with the water of mountain regions that are to a large extent taxed in the lowlands, where the companies are located. The Canton Solothurn (where Alpiq is sited) has stopped negotiations, because points of views were said to be not compatible. The Federal Supreme Court will decide. (“Neue Zürcher Zeitung” of 25.9.2013)

Pumped-storage power plants proven concept

The Grande Dixence SA and her partner, the Forces Motrices Valaisannes, have announced that they want to extend the Grande Dixence to become a pumped-storage power plant. At the moment in this region the pumped-storage power plant Nantes de Dranse is under construction. The project RhoDix shall have a capacity of 2,000 megawatt and will thereby be even bigger than the huge station Linthal 2015, that is under construction in the Canton of Glarus. The water would be taken from the Rhone and would be pumped at two levels from 500 to 2240 metres into the Lac de Dix. To that end there are two huge pumping caverns being planned that can pump up 40,000 litres per second. At a first glance this is a losing bargain, because the pumping costs more power than later can be “turbined” respectively produced by the station. Anyway it adds up. Water is pumped up when there is abundant power in the market and the prices are low. The power can be produced later straight on the point, when the demand resurges and the prices are high. A storage power plant can produce power to order within two minutes and feed it into the grid. The costs for this undertaking are estimated at 800 Million Francs. Alpiq, Axpo, BKW and the industrial plants of Basle, the owner of Grande Dixence SA, will lance the project, only when the conditions of the “Heimfall” are clear. (“Walliser Bote” of 9 February 2013)

Within the next years many pumped-storage power plants are likely to be built – especially in mountain countries like Switzerland, Austria, Spain and Norway. The main reason is obvious. The percentage of renewable energies increases permanently. The big fluctuations in power production, that inevitably emerge with wind-parks and photovoltaic could be compensated by them. But – does it really work?

One-sided focus on solar and wind energy leads to dwindling electricity prices

Recently, however, there is skepticism about the construction of pumped storage plants. The Berne power plants BKW have put the project Grimsel 3 on hold because it could not be operated profitably. Lucius Theler states his concern “if pumped storage plants are already yesterday’s news?” in his article in the “Walliser Bote”, dated 30 March 2013. Big plants such as Lintharena-2015 (for 2 billion) in the Canton of Glarus and Nantes de Drance-2017 (Valais, for 1.84 billion Swiss francs) are currently being built and will generate as much electricity as a nuclear power plant. What led BKW to their decision to stop Grimsel 3 which does not fit into the Federal Council’s Energy Strategy 2050?

Temporarily there is now a massive excess supply of electrical energy in the European market, and prices have fallen sharply. Germany in particular has massively built up wind farms and photovoltaic parks with huge capacities on the sea and on the land that are heavily subsidized. Even though, the German households still have to pay a high price for their electricity because they have to pay a massive surcharge of more than 50% to cover the subsidies. A household today pays a horrendous average of 35 cents per kilowatt hour, throughout Europe the highest price for electricity. It is expected to rise to 40 cents by 2020. As the former Federal Minister Altmeier recently pointed out, by 2040 the energy cost for taxpayers and consumers will be 1,000 billion euros. Today, Germany pays 20 billion euros of guaranteed feed-in tariffs each year that make wind and solar power systems even for small producers a viable business. Critical voices complain that things are going wrong since an overall concept is missing while changes are pushed too quickly.

The main problem is that nuclear and coal power plants cannot be turned off despite surplus production, because there are days when there is no sun and no wind. On sunny and windy days, however, there is – together with the concurrent nuclear and coal power plants – far too much power, which is called “disposable power”. The price temporarily drops below zero. This surplus is passed across the free European electricity market to the neighboring countries, pushing down the price there. This in turn means that hydro power – the “old” renewable energy in Switzerland – can no longer cover its cost. On average, electricity is traded at 4 to 5 cents at the European Energy Exchange. This price is below the production cost of existing Swiss hydro-power plants, which are at producing electricity at 7 cents. In new or upgraded plants, according to a study by the Federal Office of Energy, these costs are 14 centimes (“Neue Zürcher Zeitung” from 13.12.2013). In other words, existing hydro power plants cannot cover their costs and new investments are not paying off, because importing is currently much cheaper than producing – a dangerous development for the country.

The director of the Central Swiss power plants CKW recently made the following statement: “The supply of subsidized energy from solar and wind power distorts market prices by 30 to 40 percent.” The BKW is going to shut down the nuclear power plant Muhlenberg prematurely – for economic reasons, that is, because even the operating costs are not covered. This way foreign dependence will rise – both on fossil plants as well as on foreign nuclear facilities. BKW has a participation in the German coal-fired power station Wilhelmshaven, which will go on-line soon. The shareholding of BKW is equivalent to two-thirds of the capacity of Mühleberg.

Uncertain future of hydro power

Lucius Theler assesses the prospects of the domestic hydro power stations in the “Walliser Bote” dated 6 July 2013 with great concern: “They are with their backs to the wall. Given the highly subsidized new renewable energies and their rapid development, they are confronted with unpleasant facts. Highly subsidized electricity comes foremost from Germany at prices below the cost of local power plants even including many hydroelectric power plants. Yet highly profitable plants must live together with sharply reduced margins. In addition, the assessment of future developments in the energy sector is like reading tea leaves. Nobody knows where we are headed – neither in the short nor in the long term. The drop of prices will also lead to a re-evaluation of the values of the “Heimfalls”. Lucius Theler concludes that hydro power is going through one of its most difficult times in its history.

The concept of delivering peak power at high prices that was well-proven for many years does no longer work. In recent decades, the electricity of pumped storage was required in each case about noon, when stoves were simultaneously switched on across Europe and they were able to provide much additional power within minutes. Recently, the storage plants get competition from photovoltaic power plants that produce most of the power that lunch time (when the sun shines). The pumped storage plants need to re-align themselves to act as “batteries” which store the electric power resulting from the inevitably large fluctuations of wind and solar power. In Germany, wind and sun plants produce less than a quarter of the 8,760 yearly hour’s electricity (“Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung” from 19 October 2013). The existing capacity of storage power plants falls far too short to close the large gaps. Numerous coal plants take on this task. More are being built. Combined with the remaining nuclear power plants this results in massive surpluses – especially when at the same time the wind is blowing and the sun is shining.

Conclusion: It is time that the hydroelectric power plants in Switzerland again receive the recognition they deserve by politics and business. As the preservation and promotion of local agricultural production is highly important for our food sovereignty, hydro power in our Alps and the Jura is a priority for a high level self-subsistence of electricity supply. In addition to the small hydro power plants, big plants such as Grand Dixence or Linth-2015 must be allowed to sell their electricity at a reasonable price. •

In the second part of this article we will discuss the power supply in the EU in more detail and address the issue of an independent Swiss energy policy.

Alertswiss is launched – help for individual emergency plans

cc. In early February 2015, the Federal Office for Civil Protection (FOCP) launched the system Alertswiss in collaboration with various partner organizations. Now everyone who is interested finds information on a website (alertswiss.ch), a smartphone app, Twitter (@alertswiss) and YouTube information about the precaution and the behaviour in disasters and emergencies in Switzerland. In the centre of the newly launched website is an individual emergency plan that every household can create for themselves. In it e.g. family meeting points can be set, important information can be deposited or a list with emergency supplies can be stored. In an emergency, it is essential that the relevant authorities and the population concerned will act as quickly and as correctly as possible, said Benno Bühlmann, Director of the Federal Office.