The art of track reading

The art of track reading

Footprints in the snow – but left by whom?

by Heini Hofmann

What natives, Indians and trappers still have in their blood, is lost to us modern people of civilization: the fine art of track reading. Only gamekeepers and hunters still learn it. Hence, let us look a little over their shoulders.

Instructions for the preservation of animal tracks

HH. Those who would like to act as deer-chasing Sherlock Holmes , can preserve a distinctive footprint of a wild animal in mud, wet soil or frozen snow by employing a plaster cast and use it for comparison purposes later on:

– Thoroughly clean the animal footprint of leaves or pine needles.

– Press a ring of stapled cardboard strips into the substratum around the footprints.

– In a tin mix a runny modelling plaster solution (alabaster).

– Cautiously pour over a small stick (thus no damage occurs and no air bubbles are trapped) until the footprint is covered by about 2 cm of the solution.

– After about 20 minutes, carefully dig out the plaster mould together with the cardboard border and leave the plaster some hours to finish hardening.

– Remove cardboard border and with an old toothbrush clean the imprint, then label it (species, location, date).

If you want to produce a positive print from this negative print, spread the negative evenly with Vaseline, encircle it again with a cardboard border and pour plaster in it a second time. This way a print results, as was found in the field.

(Translation Current Concerns)

Just as our shoes, bicycle or car tires, the feet of animals leave footprints behind when moving in snow, mud, sand or wet soil. These animal tracks are most obvious in the fresh snow. One, who knows how to read them, will find a book open inspite of seven seals.

Footprint, track and trace

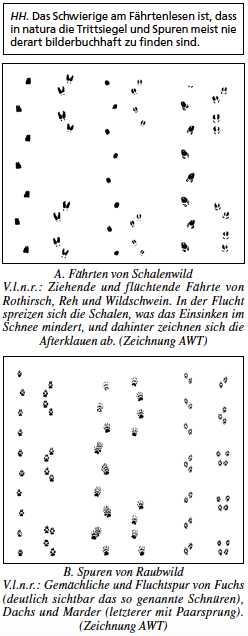

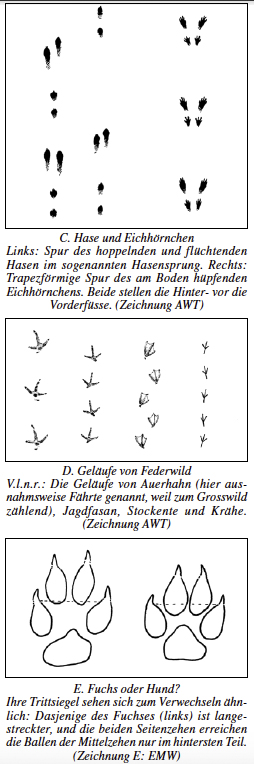

The single footprint, called foot seal, is typical for each species, depending on whether in mammals it is a plantigrade (paw of the badger), a digitigrade (paw of the fox) or a tiptoe digitigrade (hooves of hoofed deer). Even with winged birds, the cursorial bird (toes of the pheasant) shows a very different footprint from a floating bird (webbing of a mallard).

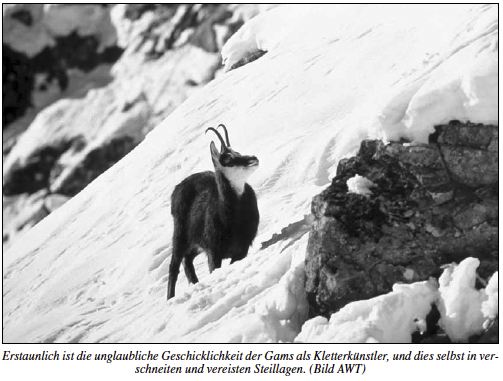

The footprints that string together when in movement form the track or trail. When deriving the footsteps of hoofed game, i.e. of deer, roe deer, rock deer or chamois or even of wild boars (boars) the expert speaks of a scent. All other step images, such as those of rabbits and squirrels or of predator game such as martens, foxes and badgers are called trails or tracks. When winged game is concerned, it is called spoors – as opposed to scent, track and trace with furred game.

And whatever can be read out of that! A footprint cannot only reveal the species, but can also say something about the sex and age of the individual. Further to the direction of travel it is also indicative of the pace, whether the animal moved along slowly, trotted urgently or whether it was even on the run.

Pulling, toddling and escaping

Depending on the type of movement, the game’s steps of the right and left legs are more or less limited according to the width of the body, with the legs set aside an imaginary centre line. There is a gap between the left and right paralleled tread, while the longitudinal distance of the individual footprints show the stride.

During leisurely pulling and rapidly trotting or trolling the hoofed game put the hind legs more or less exactly in the footsteps of the forelegs, so that such footprints effectively consist of two superimposed kicks, namely the rear above the front leg-footprint.

When escaping, however, equalling a gallop, the movement occurs abruptly from the repulsive hind legs on the forelegs, while the rear fly over the front, so that the former face the latter, and thus much more, the faster the escape.

Stringing, hobbling and nailing

Individual species also show very particularly typical lane images. Such is for example the running of a straight line (quiet trotting) of predator game. This is particular pronounced with the fox when putting the print of the forelegs as well as the hind legs exactly onto each other as well as without any gap straight in succession, whereby the trace image resembles a string of pearls.

This is quite different with hares: As they only walk in two very similar ways, hobbling or fleeing, they show a completely different track, namely the so-called hare jump. The hind legs here do not step into the footsteps of the front limbs, but the much longer hind legs are put in pairs in front of the shorter forelegs. With squirrels it is the same.

Martens also move hopping, however, they put the treads of the front into those of the hind legs, so that the track sequence shows only two pairs of parallel footprints. Another special feature of the badger’s trace is, when the powerful claws of its front paws imprint the treads in front of the toe pads and this way leaving behind a kind of “nailed” track.

Fascination and thought incentive

Animal tracks and trails in the snow are a fascinating phenomenon, so to speak, the mute sign language of the animate nature. They are indirect evidence of wild animals searching food or establishing social contact. If, however, flight-tracks are dominating, which unfortunately is increasingly the case, this is cause for concern.

Despite some ingenious survival strategies of wildlife, the winter, especially in the mountains, means a balancing act between life and death. Any additional disorder – for example, by winter sports enthusiasts away from the slopes and trails – causes unnecessary wearing out of the animals, this way putting their lives at risk since they are living at the energetic subsistence level.

Therefore, let us show consideration of the wildlife during winter sports - especially in mountain winter – and let them rest in their shelters and let us not disturb them in their social structure. Much rather we should be pleased with the tracks and traces in leisurely gaits, free of fear, flight, and perhaps fatal stress. •

(Translation Current Concerns)

Avoid disturbances!

HH. If you like to go for animal tracking à la Winnetou in winter, you can do so with pleasure without disturbing the deer, if you abide by the following rules:

– Don’t leave the paths. You don’t need to, because the deer’s tracks cross the human footpaths, anyway.

– Stick to existing routes, also on skis or snowshoes.

– Avoid dawn and dusk. These are the times when the deer is on its way.

– Keep out of protected zones and sanctuaries. Avoid deer yards, as well.

– Leash the dog, in case you have taken it along.

Such considerations will hardly reduce you own pleasure, but help the deer to avoid unnecessary waste of energy due to provoked fleeing – so that it may survive the severe winter time just for this reason.

(Translation Current Concerns)