Swiss cultivated mushrooms – fresh harvest all year round

Swiss cultivated mushrooms – fresh harvest all year round

by Heini Hofmann

Since mushrooms have a permanent place in healthy diets and wild mushrooms, however, are only seasonal and not available in sufficient quantity, the increasing demand is covered by cultivated mushrooms by an innovative industry that, in addition to the familiar mushrooms de Paris, launches more and more new “exotics species” on the market. Thus the wild mushrooms are not overused.

About two railroad cars full of fresh mushrooms are eaten in Switzerland every day, of which about 90 per cent come from domestic breeding. They are provided by about a dozen of smaller and larger companies that are joined together in the “Verband Schweizer Pilzproduzenten VSP” (Association of the Swiss Mushroom Producers). However, the knowledge of the methods of cultivation is limited to only few mushroom species. Only for culinarily interesting species such as chanterelles, porcini, morels or truffles they are nothing more than a fantasy.

Market leader agaricus

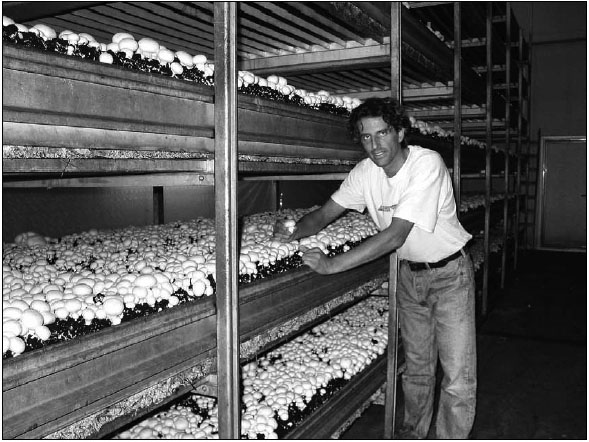

The most important and at the same time most selling mushroom produced in Switzerland is the classic mushroom de Paris (agaricus bisporus), either the white (crisp, with fine aroma) or brown one (with more intensive flavour), sometimes small for appetizers, sometimes big for the grill. Mushrooms de Paris enrich the menu all year and variously – as a main meal, as a garnish to other dishes or in sauces. Until the mid-nineties, the production could be increased continuously; since then the amount has stabilised at around 7,000 tonnes.

At the court of Louis XIV the agaricus bisporus has already been regarded as a delicacy. In 1670 a gardener in Paris discovered that the field mushroom can be cultivated. It was found that it is sensitive to light and grows best in dark cellars and vaults. Highly specialised mushroom production facilities with modern plantation rooms gradually developed from former farms with mushroom growing as a niche division.

Unlike vegetables, where an effective border protection exists, the domestic mushroom production competes against largely open borders. What matters to hold ones ground against foreign competitors, are optimum quality and efficiency. Deciding criteria for choosing mushrooms from the store shelf, are freshness, appearance and confidence in the product. Therefore, the integrated production was introduced in 1997, the certification according to Eurepgap was realised in 2004 and Suisse Guarantee, which is standard today, was added in 2005.

Production and handling

Raw material for mushroom production is a special soil from fresh organic materials, the so-called substrate. This is irrigated, composted and pasteurised several days. Subsequently, the mushroom seed, the mycelium, is applied. The substrate interspersed by mycelium is placed in air-conditioned rooms in huge patches, and the necessary microclimatic conditions are created. Lowering the temperature will stop the further growth of the mycelium and will lead to the formation of fruiting bodies.

From feeding the cultivation areas until the start of harvesting the mushrooms, it takes about three weeks, as long as it subsequently takes to harvest by hand. After buying the mushrooms they can be stored in the refrigerator for several days, but not in a plastic wrapping: they must be able to breathe. Pressure and friction generate brown spots on the snow-white mushrooms that do not have to be cut away, since they neither affect flavour nor durability. Cleaning is carried out – if necessary – briefly under running water (no watering!). Should they have been kept in a cool place, mushrooms can also be warmed up again easily.

“Exotics” on the rise

Since success requires innovation and new products stimulate consumption, the mushroom producers entered new territory and included additional species, the so-called “exotics” in their programme. From the mid-eighties it has been the shiitake originating in China, which has been called the aromatic because of its spicy flavour. Today it is – after the agaricus bisporus – already the most widely consumed mushroom in Switzerland.

Since the early nineties, the oyster mushroom or pleurotus (commercially called pleos), originally a wild mushroom, with roof tile shaped, fleshy hats and a taste between porcini and chanterelle and suitable as a meat substitute, has been added. The king oyster mushroom of Mediterranean origin, firm to the bite, with a slightly sweetish taste and meaty texture, which is often used in the kitchen as a substitute for porcini, is related to it.

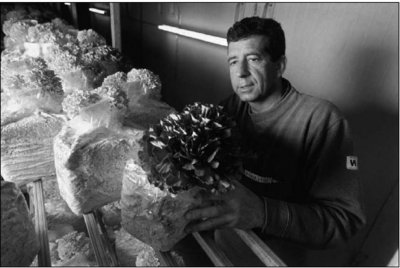

Even the grifola from the family of poriaceae, which belongs to the endangered species in nature, is a newcomer in cultivated mushrooms. It impresses with cauliflower-like appearance, crunchy consistency (after preparation) and slight flavour of nut and pepper. Yet it is exclusivity, but it is becoming increasingly popular.

Different acceptance

The mushroom producers are testing new species repeatedly, whereby two factors are of interest: cultivation and market potential. Hence experiences fall out very different. Not all newcomers have been proven popular; for example, pom pom, the rare coming from China – smelling of coconut, lime and citrus flavour – has not achieved the expected results. Although it resembles chicken and veal and can be prepared like a veal cutlet as Piccata, its market opportunities remain low.

As distinguished is the situation with the shimeji or beech mushroom: this intensely white and tasty mushroom is tender and yet firm to the bite, spicy and of slightly nutty flavour. In China and Japan it has been cultivated for a long time, and has developed to the most eaten of all mushrooms in China. In Switzerland, the production of shimeji is still in the start-up phase, which is why it has not yet come into appearance in large quantities on the market. But the odds are in its favour.

From wild mushroom to cultivated mushroom

Unlike the mushrooms, the “exotics” are not grown on large patches, but on crop-production units in the form of substrate blocks, requiring a lot of effort and commitment, though. If you are going to introduce a new species onto the market you have to start studying specialist literature and the list of the mushrooms permitted by law. Then a suitable candidate must be sought in nature and it has to be evaluated, if the species that has not been cultivated so far will be attractive in taste. Only now efforts to its cultivation can be made.

This is done either by inoculating the substrate with tissue cultures or by spore germination. These spores and tissue cultures are added to a malt-agar growth medium in test tubes or petri dishes. If all the necessary conditions are met for germination, a mycelium will be the result. From now on the ambient conditions are deliberately modified to accelerate the growth and induce the formation of fruiting bodies.

Often years of test phases

The coordination of all parameters – optimum temperature, proper humidity, best source of nutrients, ideal ventilation – causes numerous test series, that may take months and years. It is also important to work with different breeding lines, since their genetic characteristics show different resilience and frequencies of reproduction.

As soon as it is possible to produce complete life cycles for a particular mushroom in the laboratory and as soon as the mycelium forms fruiting bodies, you can proceed to the pilot phase. This requires a first-class and low-cost substrate, ideally from waste products of agriculture and forestry. Now it is time to check the acceptance by trial promotions. Only if these will be positive, then the industrial production can be started, accompanied by clever marketing for the new product. In other words: The success story of cultivated mushrooms has therefore not yet been written to the end! •

<link http: www.champignons-suisses.ch>www.champignons-suisses.ch and

<link http: www.pilzrezepte.ch>www.pilzrezepte.ch

(Translation Current Concerns)

Tips for preparing mushrooms

Mushrooms are multifactorial foods; they can be boiled, steamed, fried, grilled, deep-fried, dried, frozen or pickled in oil and vinegar. (Some – such as champignons, oyster mushrooms and king oyster mushrooms – are even suitable for raw consumption.)

And they can also be consumed reheated; leftovers should be kept refrigerated and only for a short time and then be warmed up to at least 70 degrees Celsius.

Cultivated mushrooms can also be preserved without any difficulty. For deep-freezing either put them thinly sliced and raw into the freezer (for example, on a baking sheet), or steam them whole or sliced during 5 to 10 minutes without seasoning in a little extra virgin oil.

Mushrooms can also be pickled in oil and vinegar, with fresh herbs or spices according to your taste. Another form of preservation is drying.