Little man, what now?

In 1932, Rowohlt Press published the novel “Kleiner Mann, was nun?” (“Little man, what now?”) written by the previously hardly known writer Hans Fallada. The book immediately became a giant success, even a world success, because it describes the period of the years 1930/31 in Berlin in Germany from the perspective of simple but honest people in an environment in which there were also more than enough dishonest people, and it is empathetic and full of detail. Enthusiastic letters were received by the publishing house, sent by people like Thomas Mann, who had just been awarded the Nobel Prize, Kurt Tucholsky and Carl Zuckmayer, and also by several apprentices who recognised their situation in the book. And yet, the text had been greatly shortened with regard to the emerging Nazis, and it was reissued after 1933 in a partially modified version in which there were no negatively drawn Nazis. This was even done with Fallada’s consent, as he could not imagine going into exile. He retired to a farm in Mecklenburg and there he wrote other well-known books besides carrying out his rural work.

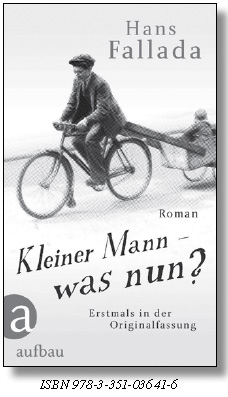

Now the Aufbau-Verlag has published the complete text for the first time, after the manuscript had been found in the archives. Reading this book is well worthwhile. For one thing, you get a very vivid and detailed impression of the situation in Germany at the time of the economic crisis at the end of the Weimar Republic. For another thing, you read a very human and touching story, which is of timeless value.

Pinneberg, a small employee, marries the woman who is expecting his child, and does his best to earn a living for her and himself, and also for their small son, in whom he rejoices in spite of all the difficulties and the spiteful remarks of people around him. He is confronted with unworthy treatment at work, and he puts up with a lot, but not with everything. He meets temptations that could lead him astray from the honest path, but he remains steadfast, even if he does not know how he will pay his rent the following month.

Since the book is not crime fiction, there is no spectacular story. The suspense arises from the fact that Fallada takes his readers with him into the small people’s everyday life. We can see what it was like in the management of a small company, or how a salesman was treated and harassed in a department store. We are in with a young couple expecting a baby and trying to get a furnished room they can afford to pay, and we feel with them when they calculate how many marks and pennies they can spend and how little they can afford. But we also learn what gives them pleasure, and that among the many repulsive people who they are, however, dependent on, they also meet compassionate people, and also how they lose these out of sight. The book is full of everyday life full of unexpected twists and encounters, which we sometimes also anticipate, and everything is portrayed from Pinneberg’s perspective – not just as external action, but always accompanied by his thoughts and feelings, his worries and hopes.

Yet Pinneberg is very lucky to have his wife – a modest person who is well able to cope with life and who keeps him without flinching on the right path from which he sometimes threatens to deviate. She encourages him with her confidence. She might almost be seen as the embodiment of the sentence “we can make it”, if this sentence had not gotten to sound so dull because of another woman from Mecklenburg. In this book, however, the confident attitude is the human leitmotif, which is presented convincingly and true to life. In the face of the adverse circumstances this woman, called “Lämmchen”(little lamb), might almost be regarded as a worldly innocent and fairy-tale invention.

But Fallada – or Rudolf Ditzen as was his real name – knew what he wrote about. Of course he wrote about himself, though not biographically but in literary transformation. He had professional difficulties himself in the twenties – change of job, alcohol and drugs, embezzlement, prison term – he was a little man himself. In 1928, he met a woman who stabilised him. Their first son Uli was born in 1930, and the family’s economic situation was fairly stable, but not rosy. In 1931, he began to write the “Little man”, and in 1932, as this was a world success, he was able to retire with his family to a farm at the end of the world, as far away from political events as possible.

His own experiences at the lower end of society, his extensive contact with people standing on the edge of the abyss, and at the same time his empathy for these people, to which when all was said and done he also belonged, his own will to lead a decent life – and ultimately his untameable narrative talent – allowed him to depict his time as vividly as hardly any other writer has succeeded in doing. And life with his wife made it possible for him to invent the figure “Lämmchen”, which is precisely not an invention – there is a live person behind it. The book is also a declaration of love he made to her.

The reviewer had the good fortune, as a child and into his adult age, to get to know this woman, Anna Ditzen, Fallada’s widow. She continued to keep the farm up into her retirement age and also rented rooms to summer guests for financial reasons. This is how we met in the 50’s. Shortly, after the German reunion, just before her 90th birthday, she died. Without her, there would be no writer Hans Fallada. She gave him four children, but he always brought her much suffering, in the end he left her, there were other women, drugs and alcohol, and he died exhausted in 1947. Yet she always stood by him and supported him, though not unconditionally: she did not accept the drugs and she did not let him into the house with drugs. But she preserved and cultivated his work beyond his death, and would not hear any-thing bad said about him; she knew that he was a weak man and a great writer. This vigorous and unsentimental woman never gave up anything or anyone, but she always looked for what was next needed and where anyone needed help. Only once she was near an emotional breakdown, and that was when her daughter Lore died. But she had to go on because she had another son, Achim, who was still a child. And she managed, also in this situation.

Whoever reads “Little man, what now?” and was so lucky as to know this woman, does not only see the 1931 Berlin rise up in his mind alive as it was. He is not only shown how to live decently though times are bad and how to rely on marital cooperation to help you find your way to this; but he can also see this book as a monument dedicated to a strong woman. •

(Translation Current Concerns)