“The result shows that we can resist bureaucracy and centralism, if we work together”

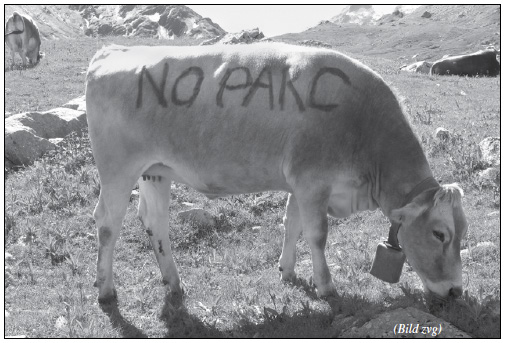

After 16 years of preparatory work and more than 10 million of subsidies from public funds in 17 affected communes, people voted on the project National Park Adula from 24 to 27 November 2016. The affected population refused the project despite massive propaganda of the proponents. In the following interview Leo Tuor, member of the committee “na nein no Park Adula” explains this result.

Current Concerns: Why is the refusal of the project National Park Adula important?

Leo Tuor: We already have a national park in the Canton of Grisons. That is enough. Additionally we have three nature parks and now there is already talk of an international park in the Prättigau Valley which shall contain the Rätikon [a mountain range of the Central Eastern Alps located at the border between Vor-

arlberg, Liechtenstein and Graubünden] as far as Austria. Effectively we could make whole Switzerland a park, do away with the 289 labels and reintroduce the old trademark, this with the crossbow, which honours Swiss quality, reliability, etc.: a red crossbow for conventional quality, a green crossbow for real bio-quality, a yellow for not convincing quality where the label is only accepted by technical reasons concerning subsidies.

The refusal of the National Park Adula is important as a signal to Berne that it is not about a restriction of freedom we are afraid of but that we are fed up with regulations. Moreover we have figured out the Swiss park concept as miserable theatre. And we disapprove of empty talk – this is about visions and planning of the future. Planned economy, merger and centralism don’t harmonise with the thinking of mountain people.

How could the small group of park opponents convince notwithstanding the financial supremacy and the enormous media presence of the park supporters?

The alternative Park Adula or apocalypse, this was a bit simple for the electors. Then: a national park is associated with nature, but the project pretended to promote the economy. Only in the lowlands it was propagated as nature park. Adula was never trustworthy, its people didn’t have charisma and didn’t take the population seriously. This was a battle of rebels against advocates. Advocates never go down well with the ordinary people. You can’t convince only with millions and blabbing, it always smelled like propaganda. The large majority was not corrupt.

What was the cooperation with the park opponents of the Canton of Ticino like?

We didn’t feel as residents of different cantons, but as mountain people/montanari, with the same identity. Language was a problem. We Romans admittedly do understand Italian but talking and reasoning is more difficult. Moreover mountain people and farmers are not so eloquent as the advocates, but we went down well with the population who is not so eloquent, too.

Even Moses had this problem with the language (Ex 4, 10) and nevertheless he lead the defiant people through the desert of life.

The controversy round the Park Adula, where we saw, that our identity – namely the mountain – is the same, brought us closer to the Ticino people. We both love the mountains, but don’t idealise them too much, because they are also difficult, bring danger and can be relentless. The cooperation was unbureaucratic and uncomplicated. We had one single meeting on the Lukmanier Pass. There only a few Grisons people came because it was deer hunt and then you can’t do anything else with them.

Which lessons did you personally learn from the whole controversy?

I learned the lesson that you have to be trustworthy and honest and that the people stick together when it comes to their being: our basis of existence are the mountains and the language, they depend on each other. Without the mountains such pronounced dialects wouldn’t exist and the Rhaeto-Romanic would have become extinct long time ago. Not too long ago it was tried to enforce top-down an artificial unified language upon us Romans: the Romansh Grischun. This multi-million francs project miserably failed because it came from Chur and Zurich. This was an urban-rural problem, too, centralism versus federalism. We are wired differently from the town people. Switzerland is no mishmash. Therefore it is interesting. Another lesson is that literature can be a sword. I am a literary man and have struggled with essays against this crazyness. Even in Giacumbert Nau (1988), my Sturm und Drang opus – a book that was for a long time indexed by the Grisons government – you can read:

“The desert grows – woe betide anyone who saves deserts!”

“Actually, Mr. President, what about you?

You soon are seventy years old and still want to sell the land? You have speculated, overbuilt, devastated your valley and now you want to whitewash your conscience with a park in the valleys of the others?

You may have an illustrious suite. But consider, there are yet others in this world. They want to live in the mountains and not in a reservation. Must you, Mr. President, an old man, keep on and on forever? We don’t care about this future you want to brew up for us in league with the town people. They have destroyed their habitats – does this give them a right to ours? Our pastures shall become wastelands? Our forests become overgrown? And we shall be their Mahicans?

Not even the stars you will leave to me. And my animals, where shall I go with my animals?

Riff-raffs, crudité shredders. Make your parks in your cities. We don’t care about the future you want to prepare for us. Leave in peace my animals that didn’t do you any harm, who rest under the starry heavens. Go to the devil with your advices. Respect us who we are not here on holidays.”

What does the result mean for the identity of the mountain people?

The danger concerning the Swiss is that everybody is looking for himself, hatching something in his region without wanting to know from each other. In the Canton of Grisons we have a kind of mini-Switzerland with the three languages and many valleys. In the Rhaeto-Romanic part with our five written languages we have a kind of mini-Grisons. And yet the Rhaeto-Romans all are hatching for themselves in their regions. The whole structure in Switzerland is a Matrioschka with babushka, every time a bit smaller, the smallest is the Rhaeto-Romanic.

The result has shown that we can resist bureaucracy and centralism if we work together. Our committee did an optimal job with minimal costs, small expenditure of time and moderate infrastructure. It was fascinating to work together with people from the left to the right without party bickering and ostentation of power.

The proponents of the park refused to see a relationship between the park and the large carnivores, what do you think about this?

This was implausible, too, because wolf and bear have to do something with nature and are totally protected in a national park. Even with a relaxing of the Berne Convention. When it was signed in 1977 we didn’t have any wolves here and therefore no problems, too. And in Grisons with so many parks the wolves have a great freedom, even to reproduce undisturbed.

It just can’t be possible that the proponents say, the national park protects nature and animals and at the same time they proclaim that there is no relationship between park and large carnivores. This is irrational and dishonest. The wolf is an important topic in the mountainous regions of Grisons and northern Ticino. Italy deals different with it, Italy is less law-abiding. Maybe we could learn something from our neighbours.

Thank you very much for the interview.

(Interview Rico Calcagnini)

* Leo Tuor, born in 1959, spent 14 summers as a shepherd at the Greina plain. 1989 – 2000 work on a six-volume edition of the Rhaeto-Romanic prince of poets and cultural historian Giacun Hasper Muoth. Leo Tuor lives together with his family in Vals. He writes novels, narratives, short texts/stories and essays, he was awarded with many prices, for example: 2012 award of the UBS cultural foundation for his complete works, Prix du Conseil International de la Chasse CIC (South Africa) for «Settembrini»; 2009 Grisons literary prize; 2007 award of the Schiller foundation. (www.tuors.ch)