The significance of direct democracy to ensure the economic and social order of Switzerland

The significance of direct democracy to ensure the economic and social order of Switzerland

After the Second World War the people decided for a new Family Article, new Economic Articles and the establishment of the OASI in the Federal Constitution

by Dr rer. publ. Werner Wüthrich

After the Second World War, there was a short period of a few years in Swiss history in which the people have laid the foundations in various referendums for the social market economy, in which we live today. The Federal Constitution was not just about new business articles, but also a family article and in a new law about the establishment of the OASI (old-age and survivors’ insurance). Current Concerns has published a series of articles entitled “The significance of direct democracy for securing social peace” (Part 1 on 2 June 2015, Part 2 on 16 June 2015, Part 3 on 30 June 2015, part 4 on 29 July 2015, part 5 on 23 September 2015, part 6 on 1 December 2015), which outlined the history of these central events for today’s Switzerland.

The year 1943 is a special year in the history of the world. The fortune of war by Hitler’s armies during the Second World War was changing. In Africa, Rommel had to withdraw after the Battle of El Alamein. Retreat started in the east as well after the defeat at Stalingrad. On the high seas, the German submarines got increasingly on the defensive and the US succeeded more and more in supporting its allies in Europe with material. In Tehran Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin met for the first time and discussed the post-war order – after the capitulation of Hitler. The war lasted longer, however, than many had expected at the time.

In Switzerland, which had fortunately been spared of hostilities, some citizens thought as early as in 1943 about the question “What’s next after the war?” The crippling mood of the thirties and the fears during the war diminished and made room for political optimism. However, unemployment remained at the top of the political agenda. In April 1943, a large, two-day national conference on “government and business in the fight against unemployment” took place at ETH Zurich, which was attended by personalities from the communes, the Federal Council, the trade unions and the business community. Three popular initiatives on the “right to work”, which were intended to rearrange the economic life, were filed during these months. The new business acts in the Federal Constitution, which were revised by Parliament, were ready for vote. But not enough. Two other popular initiatives were added in these months trying to answer the basic social policy issues of social life: namely the protection of the family and the pensions. The people were wondering.

Provision for old age yes – but how? First attempts

As early as in 1925, the people had agreed in principle on a constitutional article establishing a retirement and survivors’ insurance. However, actual implementation in a federal law was not so easy. In 1930, the Federal Council and the Federal Parliament had drafted an OASI (old-age and survivors’ insurance) act together with insurance experts – namely taking the following approach: The public insurance should be mandatory and – similar to today– be financed through payroll deductions and employer contributions. Funds from the tobacco and alcohol tax would be added. The insurance should – again similar to today – function according to the PAYG system, i.e. the premiums received should be immediately paid out again as a pension to old people. Unlike today, however, the premiums and pensions were uniform, i.e. regardless of income, and very modest. A man paid 18 Swiss francs, a woman 12 francs premium a year. The employer’s contribution was 15 francs. The annual pension after the age of 65 should be 200 francs for all. This was little, even taking into account the decrease in value of the money in the 20th century.

This OASI was intended to be a minimum insurance and from the outset it was based on the citizens making provisions within the family and the cantons setting up supplementary insurances. The canton of Glarus had led the way. Already in 1918 the “Landsgemeinde” (communal voters’ assembly) had adopted an OASI and a disability insurance in an open ballot. The unified pension amounted to 180 francs per year from the 66th year of age and then increased every year. Previously the citizens’ meeting had already agreed on an unemployment fund. Glarus thus lived up to its reputation as a pioneer canton, since the “Landsgemeinde”had already decided in 1863 on the first modern factory law at that time – Europe-wide. The concept of retirement funds based on three pillars in the thirties: 1. the self-provision in the family, 2. the public or private pension scheme and 3. the welfare for the elderly, which was paid by the communes and also by non-profit organizations (such as the “Foundation for the old age” (now Pro Senectute)). They helped in cases where there was not enough money. Communes also ran citizens homes – which originally were, as the name suggests, associated with citizenship. They cared for and maintained those elderly who were no longer able to care for themselves.

OASI without social compensation

From today’s perspective we immediately become aware that social compensation was completely absent in the planned pension scheme of 1931. Rich or poor should pay the same premiums and get the same pension in later years. In Parliament all major parties voted in favour, even the Socialist Party. However, there were citizens and smaller parties that did not agree with it. The Communists advocated a kind of people’s pension and rejected the submission because the pension level was fixed too low. They spoke of an disrespectful “pauper’s broth”. Catholic circles were oriented towards the papal encyclical “Quadragesimo Anno” and wished for an old age provision borne by the family, the professional communities and the Church. Liberal circles saw the OASI rather as a private matter which they wanted to complete by a voluntary pension insurance and supplemented by welfare for the elderly supported by the federal government. They claimed it was the only way to prevent people from receiving a state pension which they did not need.

As happens often in such a situation, citizens who did not agree started a referendum (which also came about). Others made a suggestion in a popular initiative on how things could be handled differently. Thus industrial circles demanded that the federal government should subsidize the welfare of the communes and cantons for the elderly – at least until an old-age insurance was established.

The people’s No had a sobering effect

The 6 December 1931 was one of the not so rare voting days on which the “Classe Politique” realized in the evening, that the people “reacted” differently from what they had assumed. Nearly 80 percent of eligible voters went to the polls and rejected the OASI in the then current form with a bulky No of 60.3 percent. This was amazing, but the Great Depression had begun with all its needs. Moreover, the vote of individual regions in the country was very different. While Zurich adopted by 57 percent, only 7 percent voted in Fribourg for this type of retirement. – The OASI was still far from being the institution underpinning the state as it is today.

After the people’s No, it was crisis and World War II that delayed the rapid development of a new submission. The federal government financially supported in these difficult years the welfare for the elderly of the communes and cantons, as the Liberals had requested in their popular initiative. However, the call for a compulsory old-age and survivors’ insurance for all did not silence.

From wage replacement of soldiers to OASI – popular initiative of the Swiss Mercantile Society SKV

During the Second World War a new idea for the establishment of pensions developed. It had its origins in the experiences of the soldiers in the militia. In early September 1939, the Federal Council had mobilized the entire army of about 500,000 troops to fend off a feared attack from the north. When Hitler attacked the Soviet Union in 1941, the active units were gradually reduced by more than half. After the Battle of Stalingrad in 1943, the number of the fighting soldiers fell temporarily even below 100,000 men. The German armies were now busy on so many fronts that the danger of an attack was no longer considered to be “high”. Some of the militiamen were able to return to work. Others, however, had to endure at the borders and in the Alps fortresses until the end. In these long years it was important that the wage substitution of soldiers in active duty was regulated. In the First World War that had not been the case, which had led to serious social tensions and was one of the reasons for the general strike of 1918 to come about.

Wage replacement of the soldiers had priority over many other things

In 1939, the Federal Council acted quickly. Already in the first month of the war, wage compensation for the soldiers was established on the following principle: two percent of the salary of those men and women who were still at work was deducted. In addition, the employer paid the same amount. This money was supplemented by public funds. A social balance was incorporated in this system, since high earners paid significantly more due to the premiums being calculated as a percentage of income. In the cantons, compensation funds were set up, which managed the funds and paid off the wage compensation to the soldiers.

We could do it just like that!

In 1942, the merchants of the Swiss Mercantile Society SKV were thinking “commercially”: Their idea was that exactly this system could be adopted for the future OASI. The well-functioning compensation funds for wage adjustment of the soldiers could be converted into OASI schemes and continued after the war. The solidarity between the people and their soldiers could be a model for solidarity between young and old, the merchants thought and did not hesitate long. They collected signatures for a popular initiative. They experienced that their arguments were convincing and their fellow citizens eagerly signed the initiative. Several times the required number of signatures were collected quickly.

It was then (and it is even today) not rare that the state government responded defensively to a new popular initiative, because it interfered with its plans. At that time, however, it was not the case. The competent Federal Councillor, Walter Stämpfli, gratefully accepted the initiative from the people. In his 1944 New Year’s speech he promised that he would draft an OASI law, together with Parliament and professionals, which contained the basic ideas of the popular initiative. Moreover, he promised that the new law would come into force on 1 January 1948. Hence the initiative committee announced that in this case, they would withdraw the initiative at the appropriate time.

Memorable 6 July 1947

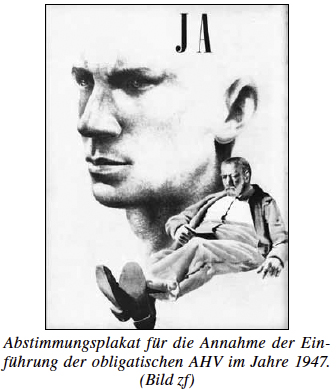

Stämpfli, who could be described as the “father” of the OASI today –, should keep his promise. The referendum against his bill was indeed – as expected – taken, and on 6 July 1947 it was put to the vote. The opponents brought forward similar arguments in their campaign as they had already done in 1931. Catholic circles wanted the retirement pension rather in the care of the Church and in the hands of professional associations. Liberal circles (who had taken the referendum) from the Romandy (French-speaking part of Switzerland) favored – similar to 1931 – a concept with a private pension scheme, supplemented with a welfare scheme for the elderly – supporting the needy – that was co-financed by the federal government. They claimed it was the only way to prevent that someone received a state pension, who did not need it. – The vote of the people was clear, however. More than eighty percent of the electorate went to the polls on this memorable day and said a clear Yes to the new OASI with almost eighty percent.

The OASI in its basic concept has been undisputed until today. It is a prime example of a law in whose creation the population was directly involved.

Popular initiative on the “Protection of the family”

Almost simultaneously with the initiative on pensions, another sociopolitical popular initiative was launched. The Catholic-Conservative Association KKV submitted a popular initiative on the “Protection of the family” in 1943 with 178,000 signatures. It should provide the basis in the Constitution, to refocus politics on family needs. As a result, the Family Compensation Funds FAK should be promoted in the cantons. Families with children should receive higher wages. Some companies had already taken this into account, however, for quite some time. The housing system should be designed family-friendly and much more.

Once again, the Federal Council and Parliament positively accepted the popular initiative. Moreover, the Parliament worked out a counter-proposal, which went even further than the proposal of the initiators (so that they could withdraw their initiative later). The counter-proposal contained an additional maternity insurance. The relevant passage in the proposed constitutional article (now Article 116) was as follows: “The federal government shall by means of law establish a maternity insurance scheme. It may also require persons who cannot benefit from that insurance to make contributions. (...)”. The new constitutional article was widely accepted by the people with a clear majority in the referendum of 76 percent Yes votes on 25 November 1945.

Yes to a maternity insurance – but how?

The implementation of the Family Article, however, was not always easy. In housing and tenancy things were designed much more family-friendly. Family compensation funds were gradually introduced in all cantons or those already existing were strengthened, but the differences were quite large. In 2006, the voting citizens said Yes to a federal law unifying the family compensation funds in the cantons, for example by stipulated minimum amounts for child allowances. This step has also been launched by a popular initiative, which was withdrawn after Parliament had drafted a counter-proposal.

In 2013, the sovereign, however, said No – by a small majority – to a new family act, which wanted to expand the “compatibility of family and work” even stronger in the Federal Constitution. So, for example, childcare facilities should be prescribed by law everywhere. The submission was accepted by the people, but failed due to the cantonal majority, i.e. the No-vote of especially the smaller, rural cantons. It was also difficult to find a solution for the maternity insurance. In the years after 1945 proposals were made repeatedly, but none obtained legal status. Later the protection of motherhood was considered in the Health Insurance Act. Women’s associations did not agree. In 1980 the Organization for Women OFRA, together with the Progressive Organizations of Switzerland POCH, launched a popular initiative and handed it in with 136,000 signatures. The Federal Council rejected the accusation of having failed to fulfill the constitutional mandate of 1945. It acknowledged that there was nominally no maternity insurance. By its very nature this insurance was, however, integrated into the social security system and would also be extended within this framework. That was not sufficient for the initiators. They demanded a separate maternity insurance with parental leave, daily allowances, employment protection and funding over pay rises. This popular initiative from the left was rejected in the 1984 referendum with 84 percent no-votes and by all cantons. In 1987 and 1999 there were two further referendums also with a negative outcome. The main issue was the question of whether non-working mothers (who had no income) should be given a daily allowance. Only in 2004 the people said Yes to today’s maternity insurance, which paid the working women 80 percent of their salary for 14 weeks after giving birth. The maternity insurance was included in the Income Compensation EO for Military Personnel – and for very practical reasons. There was money that was not used in the now smaller army and could now be used as income replacement for working mothers. Thus the maternity insurance returned after nearly sixty years of debate with numerous referenda to the starting point of today’s social insurance: to the wage replacement order of the soldiers in the Second World War.

The people point the way to a social market economy

Let us go back in the years after the Second World War: The referendum on a new family policy in November 1945 was only the prelude to a series of groundbreaking referendums that have shaped the social market economy until today. This major political discussion focused on the reform of economic laws. It had become necessary because numerous emergency legislation adopted by federal decrees in the thirties violated the fundamental right of freedom of trade and commerce. They were limited and had often been passed in a flash, so that a reliable legal framework had become urgent as the legal basis for economic policy. On top of that numerous popular initiatives had initiated the constitutional debate in the thirties. (cf. parts 5 and 6 part of this series of articles in Current Concerns of 23 September 2015 and 1 December 2015). Reform work of the Parliament was finished at the beginning of the Second World War. The referendum was to be held after the war.

What were the main points of the proposed reform of 1939/1945? The core of the economic articles in the Federal Constitution was the freedom of trade and commerce as a fundamental right of the citizen and as a guiding principle for the economic order. (cf. part 2 of the series of articles of 16 June 2015). They both remained untouched.

The authorities should, however, receive new extended powers to intervene in the economic events. The federal government should be able to take measures on the “pursuit of trade and commerce” and on the “promotion of individual sectors and professions”, while it would remain bound by the principle of freedom of trade and commerce. In five areas, the federal government could take action in the overall interests and, if necessary, deviate from the freedom of trade and commerce – namely

1. to maintain existentially vulnerable sectors or professions,

2. to maintain a healthy peasant class and a powerful agriculture and to consolidate the ownership of agricultural property,

3. to protect economically endangered parts of the country,

4. to combat the misuse of cartels and price fixing,

5. to ensure the country’s supply – even in crisis and wartime. Furthermore, the federal government could establish rules on the protection of workers, on the relationship between workers and employers, on vocational training, on the job placement, on unemployment and on unemployment benefit.

Collective job agreements could be declared generally binding, so that their peacemaking action could unfold not only for the participating organizations but in an entire industry.

The new economy laws would upgrade the economic and professional organizations very generally by granting them the explicit right to be consulted in the legislative process (consultation process). This was not new, however. The business associations, trade unions and in particular the agricultural organizations have always played an important role both in the preparation and the implementation of the laws. The administration relied on their expertise.

The draft economic laws were discussed for a second time briefly by the Parliament in 1945. The Federal Council sent it along for the later vote as follows: The new economic constitution would uphold the Right to Work, keep to the liberal economic system and take account of social democracy.

Reactions

However, the draft of the Parliament should not remain without contradiction. In 1943, three popular initiatives were submitted, all of which were discussed only after 1945. They all had the “Right to work” as their topic (cf. the details on this in part 6 of the series of articles in Current Concerns of 1 December 2015):

1. The Social Democrats wanted to abolish the freedom of trade and commerce and let the economy increasingly be directed by the state.

2. Gottlieb Duttweiler and the Ring of Independents refused to accept that the “old” economic liberalism should be limited by more laws and regulations. In their initiative they demanded more economic freedom associated with a greater reference to ethics and responsibility, in order to reconcile capital and labor.

3. In the field of agriculture, the Young Farmers (Farmers’ homeland movement) demanded a new land law which connected the soil with the work. Only those should be able to purchase agricultural land who also worked on it for their livelihood.

After the Second World War the people were facing the challenging task to take a stance in numerous polls on fundamental issues of the economic order, the pension and the family protection and to pave the way into a new era.

The results

The Ring of Independents’ initiative on the “Right to Work”, which wanted to combine economic freedom with social attitude and responsibility, was clearly rejected by 81 percent No-votes in 1946. The initiative of the Social Democrats, who wanted to put the economic system in principle on a new basis, was also significantly rejected several months later with 69 percent No-votes. On 6 July 1947, 53 percent of the people said ‘yes’ to a reform of the economic laws, which Parliament had drafted (today’s constitutional Articles 27 and 94–113). One reason for the rather scarce vote was that the SP – the then largest party in Parliament – had voted against it, because the draft would support full employment too little. The Socialists’ fear that it could lead to a post-war crisis, proved to be unfounded in retrospect. Unemployment should be no longer an issue in Switzerland for a quarter century – on the contrary.

In another vote, the popular initiative of young farmers was rejected after Parliament had drafted a bill to preserve the rural estates, which granted privileges in land acquisition and inheritance to members of the farmer’s family and the farmers. The new Family Act (today’s constitutional Article 116) and the Federal Law on the OASI which – as already mentioned – was adopted by the people on the same day as the economic acts with an overwhelming majority of nearly eighty percent of the votes, completed the voting round in the forties.

There have been many other polls in the social and economic sectors to this day. They ranged within the framework that the people had set in the postwar years. OASI was often voted upon – for example on the amount of pensions, the deductions from wages, retirement age, the additional financing via value added tax and much more. A few years after the founding of the OASI, disability insurance was set up on the same principle. In 1972, the 3-pillar model was embedded in the Constitution – with the OASI, IV (Invalidity Insurance) and EO (Compensation for loss of earned income during military service, civil service, community service or maternity) as the first pillar, the occupational pensions as second and private pension schemes as third pillar. Once again, the people agreed with an impressive 74 percent of yes-votes. Several popular initiatives of the Left were clearly rejected since they wanted to convert OASI into a national pension.

Referendums secure social peace

These historic votes established the constitutional foundations for today’s modern Switzerland immediately after the Second World War. In the economic sphere there was a “small total revision of the Federal Constitution, which on the whole has been maintained to this day” (Alfred Kölz). The referendums on retirement and family protection were no less important. They shaped the market economy, the social character, which we know today. The interaction between government, parliament and people had worked perfectly, so that the economic system in combination with its social orientation represents an image of Swiss democracy today.

It is striking how real and lifelike direct democracy has worked in those years, and how many signatures were then collected for the popular initiatives. It is impressing how many voters went to the polls, even though the topics were rather demanding. It is amazing how naturally very different sections of the population from the German, French, Italian and Romansh speaking Switzerland took up their rights as a people and were thus directly involved in the construction of modern Switzerland. – Moreover, it is noteworthy to say that quite a few points of those popular initiatives that were once rejected later made their way into the Federal Constitution or in the legislation. For example, certain decisions of associations can be declared generally binding, as had demanded a popular initiative already in 1934, wanting to give the associations and professional associations more political weight at that time (cf. part 5 of 23 September 2015). The Right to Existence (which is based on the Right to Work and was included in several popular initiatives) is explicitly guaranteed today in the Federal Constitution – on the one hand directly on the Right to assistance when in need (Federal Constitution Art. 12 ) and on the other hand indirectly through the developed network of social insurance. It is further apparent that it would be wrong to reduce the economic constitution simply to the freedom of trade and commerce – today’s economic freedom – and its numerous variations. This freedom right is probably the most basic legal pillar of the liberal economic system and represents a liberal economic system of the private sector. This only works, however, because it is embedded in a national context and also regulates social spheres. It is further supported by a stable monetary system and supplemented by a public sector which is now called the Public Service. And last but not least it works because the food supplies are backed up from our own country – at least to a greater extent. These are other areas that are yet to be examined from the perspective of direct democracy.

Successful model

The many referendums at the federal level that are taken on a mandatory level or brought about the people’s rights, determine the economic and social life in Switzerland. Then there are the countless other votes in the communes and cantons in which citizens express their diverse interests and political views. The fact that the representatives of the people often do not represent these voices of the people correctly in parliament can be observed in many of the votes described above. It has been found that really viable, future-proof political solutions often only arise from the interplay of Parliament and the people – and sometimes it requires several polls to realize them. It actually takes time, which is not detrimental to the quality – on the contrary.

From various sides, criticism is raised today against individual popular initiatives at the federal level. They are said to violate international law or the principle of separation of powers. Sometimes people demand that the number of signatures has to be increased or that more popular initiatives should be declared invalid by Parliament. There are also other voices. The constitutional lawyer Zaccaria Giacometti, for example, in a famous sermon in 1954 as rector of the University of Zurich honored the people as “guardian of human rights” (cf. part 3 of 30 June 2015).

Today’s criticism distorts our view on the whole and on the significance of people’s rights. The numerous referendums at the federal level (more than 600 since the establishment of the Confederation) and the numerous submitted popular initiatives (over 300 since the introduction of this people’s right in 1891) represent life and social development in Switzerland in their variety and in their dynamism. They are an expression of the social nature of man in their creative power – far stronger and more immediate than the pure representative democracy, in which people hand over their political affairs and let themselves be represented. Therein lies perhaps the secret to the success of Switzerland. •

Alfred Kölz, Neuere schweizerische Verfassungsgeschichte (mit Quellenbuch), Berne 2004

100 Jahre Sozialdemokratische Partei, Zurich, 1988

Häner Isabelle, Nachdenken über den demokratischen Staat und seine Geschichte, Beiträge für Alfred Kölz, Zurich 2003

W. Linder, C. Bolliger, Y. Rielle, Handbuch der eidgenössischen Volksabstimmungen 1848–2007, 2010

Bruno Hofer, Volksinitiativen der Schweiz, 2012

Ernst Nobs, Die Glarner Alters- und Invalidenversicherung, in Rote Revue (Socialist monthly paper) vol. 6/1926

Delegierter für Arbeitsbeschaffung: Staat und Wirtschaft im Kampf gegen Arbeitslosigkeit Bd. I und II, Zurich, 1943

René Rhinow, Gerhard Schmid, Giovanni Biaggini, Felix Uhlmann, Öffentliches Wirtschaftsrecht, Basel 2011