“Evening bells on the Volga river”

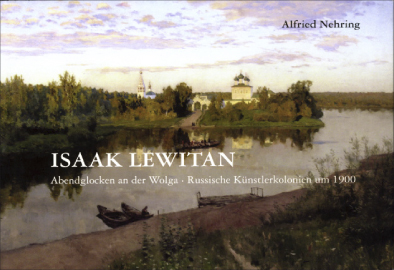

In the current tense world situation the publication of a beautiful art book about the Russian landscape painter Isaac Levitan (1860–1900) is very meritorious. With the richly illustrated publication by Alfried Nehring “Isaac Levitan – Abendglocken an der Wolga – Russische Künstlerkolonien um 1900 [Evening Bells on the Volga river – Russian Artists’ Colonies around 1900]”, the unifying quality and the “great tradition of Russian culture and its importance for Europe”, is to be emphasised, according to the author. The focus is on the most important creative period from 1888 to 1895, in which the artist painted his unique and lyrical Volga landscapes. “His working methods, which are akin to the awakening of European art in the artists’ colonies of the 19th century, is particularly illuminated,” the blurb reads.

What is special about Alfried Nehring’s publication is the portrayal of the artist’s life and work as well as the thorough processing of valuable archive material and letters about the artist and his environment. Nehring, together with his wife, visited museums, Levitans’ sites of art, and artists’ colonies in Russia, and intensively studied the young artist. The portrayal of the lifelong friendship with the writer, dramatist and physician Anton Chekhov (1860–1904), who was of the same age, was central. “Both stand for the development of a national identity of Russia and its artistic appeal to Europe.” Maria Pavlova, the Chekhov’s sister, became a close confidant of the painter. The relationship with the art collector Pavel Tretyakov, who recognised the extraordinary talent of the painter early on and supported him with purchases, was of great importance to Levitan. In the world-famous state Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, the pictorial treasures by the painters of realism can be admired.

Landscapes as an expression of the Russian soul

Born in 1860 in Kibarty (today Kibartaj, Lithuania), Isaac Ilyich Levitan was raised in a poor Jewish family and had three elder siblings. His Jewish roots were very distressing for him and the family in Czarist Russia. The author of the book writes: “On the basis of a tsarist decree forbidding Jews to live in the Russian capital, the police expelled Levitan from Moscow in 1879.” (p. 17) The father taught children of wealthy Jewish families. In spite of poverty, Isaac was able to complete his education at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture as a student of A. K. Savrassov and W. D. Polenov. On account of his great talent, he was waived the study fees. The artist reminisces gratefully his first teachers: “Since Sawrassow, lyricism and boundless love for the homeland have come into landscape painting.” (p. 17)

His works are deeply felt pictures of nature, which also reflect various mental states and emotions. Former students reported on how he could look forward to the simple and natural: “He left the city early in spring, enjoyed the beauty of the awakening life amidst the thawing snow. Sawrassow then came into the studio quite aroused, and reported his walk as if it had been a special event, only to lead the young people into the green forests and fields immediately afterwards.” (p. 18) Levitan was elected to the “Imperial Academy of Arts” not until 1898, at the time when he was named the head of the Landscape Studio teaching the landscape painting class for two years.

Love to the grown and social bonding as a core of culture

Besides his stays in Moscow, in the Crimea and in some European countries (also Switzerland) his numerous trips and especially his stays on the Volga were central. Important for his artistic development were the contemporary painters and his contribution to the exhibitions of the famous Russian “Wanderers”, a cooperative for travelling exhibitions, founded by Sawrassow in 1871. Numerous famous painters such as Repin and the circle around Tolstoy participated in that cooperative.

These artists created their close to real life studies and pictures directly in the landscapes and in contact with the rural population. They exhibited the works in and particularly outside the cities. “Like most painters from the ‘Peredvizhniki’ association, Levitan has already set a title for the planned painting at the beginning of the work, which goes beyond the description of the motif and reveals a spiritual dimension.” (p. 40) Most of these artists have a humane, ethical and social focus. In the artists’ colonies poets, painters, musicians and scientists cross-fertilised in an interdisciplinary exchange. Similar movements and artists’ colonies existed in the 19th century, for example, in France with the “Barbizon painters” and in numerous other European countries. Isaac Levitan also motivated his students to participate in the Wanderers movement: “Today I will travel to Petersburg. My students make their debut at the exhibition of the ‘Peredvizhniki’. I tremble more than myself.” (p. 59). In the summer of 1900 the artist of international fame was invited with a large work exhibition to the art exhibition in the Russian pavilion of the Paris Exposition Universelle.

After “years of disputes between the Academy of Arts, which was directly under the Tsar,” and the Peredvizhniki, and also through the pioneering collecting activity of Pavel Tretyakov, Alexander III. now recognised the great value of this national and modern Russian painting.

The Tsar, on a visit to the 17th Travelling Exhibition in 1889, announced his plan to found a Russian National Museum in St. Petersburg, which was then realised by the heir to the throne, Tsarevich Nikolaus II.

Levitan was previously invited to numerous other exhibitions on Russian art, including the Secession art exhibitions in Vienna and Berlin. Vassili Polenov was another important teacher of Isaac Levitan. He took him to his studio and introduced him to the artists’ colony of Abramzevo, the Russian railway king Savva Mamontov, and a friendly relationship developed.

In the artists‘ colony “the most important painters in the late 19th century, Ilyia Repin and Valentin Serov” (p. 21) were guests. Here, for example, Ivan Turgenev worked on his novel “The Nobility Nest”, Nicolai Gogol on the novel “Dead Souls” and other great Russian poets of the 19th century. The artist took part in the cultural life. He also passionately loved the soothing effect of music “and took up its beauty with sensitivity.” (p. 48) He transferred this stimulating social and mental climate to his profound landscapes. Isaac Levitan fell victim to typhoid fever in Moscow and on the advice of his friends traveled to Italy in 1890 for a cure. “The sun of the southern skies awakens a new sense of color with him, which later also has an effect on his work in Russia.” (p. 40). In 1895, like many others, the painter turned again to the Volga theme. World famous became Ilyia Repin’s great work “Barge Haulers on the Volga” (1873). Levitan “paints the river as a place of bustling activity in light gay colours. The painting, with its new life-affirming view, appears as a great declaration of love to the Volga and forms the conclusion of the works in which he designed the multifaceted stream as a life-line of Russia.” (p. 55)

His friend, Anton Chekhov, always looked after his health and moods as a doctor. In spite of health problems, the artist created many masterpieces that reflect the Russian soul and the intellectual climate of Russia. Prior to Levitan, nobody could portray nature that empathetic in its own poetry and almost spiritual radiance.

The young poet and admirer of Russian culture, Rainer Maria Rilke traveled to Russia to visit an art exhibition. He was inspired by his patroness and lover Lou Andreas-Salomé, who was born in St. Petersburg. In doing so, the works of Levitan appeared to him “like pearls or stars of the first magnitude” (p. 67) He wanted to visit the artist in the Moscow studio. Unfortunately, it did not work out. Instead, he met with Leo Tolstoy.

After years of illness, Isaac Levitan died much too early in Moscow in 1900. Alfried Nehring, the author of the beautiful art book, gives us a few lines from a letter by Rainer Maria Rilke, written on a Volga trip: “With these days we are taking a big step towards the heart of Russia, the beat of which we already listen to for a long time in the feeling that there is the right cycle extend also for our lives [...]. At this moment, when I write to you, it (the world) fully resembles the paintings of Levitan […].” •

(Translation Current Concerns)

2017 ISBN 978-3-941064-66-9, can be ordered by the author’s own publishers (www.isaak-lewitan.de).

The book by Alfried Nehring, Isaak Lewitan, 2017 ISBN 978-3-941064-66-9, can be ordered from the author’s own publishers (<link http: www.isaak-lewitan.de>www.isaak-Lewitan.de).The theme and the ethical realism of the Peredwizhniki were presented in detail in Current Concerns, No. 24/2015. (<link en ausgaben nr-24-15-september-2015 kunst-als-lehrbuch-des-lebens.html>www.zeit-fragen.ch/en/ausgaben/2015/nr-24-15-september-2015/kunst-als-lehrbuch-des-lebens.html)