Poems and ballads – treasures of the German-speaking poetry

Poems and ballads – treasures of the German-speaking poetry

by Ludwig Murtinger

Again and again I feel compelled to take one of the books which have grown dear to my heart in my childhood. One of them has always accompanied me. I still draw upon this today many things, which is important to me in everyday life. It is “Das grosse Balladenbuch (he Great Ballad Book)”, in which the most beautiful and important works of German-speaking lyric poetry were published and recommended to children and teenagers. Today, of course, I have a variety of poetry and ballad books, and in all are collected real treasures of the poetry. A passage from Goethe’s “Notes and Essays on a Better Understanding of the Western-Eastern Diwan”, in which he mentions the poetry, is quoted in the entrance to the “Great Ballad Book”:

“There are three genuine natural forms of poetry: the clearly narrative, the enthusiastically excited, and the personally acting: epic, lyric, drama. These three types of poetry writing can act together or separately. In the smallest poem they are often found together, and by this unification in the narrowest space they produce the most glorious form, as we perceive in the most esteemed ballades of all peoples.”

For me, personally, it is the great wisdom expressed in the poems and ballads, which fascinate me and affect me. From today’s point of view, deep psychological insights and awareness often come to the fore, and guidance on the highest human level plays a central role. We know many examples for that: “The pupil in Magic”, “Belshazzar”, “The Cranes of Ibycus”, “The Bard’s Curse”, and many more. It always fulfils me with a profound sense of reading Schiller’s “The Hostage”, the value and the meaning of friendship expressed there cannot be represented more dramatically and poignantly. But other, smaller and less well-known works are true treasures of literature: for example “Das Riesenspielzeug” (“The Giant Toy”) by Adalbert Chamisso or “Herr von Ribbeck auf Ribbeck im Havelland” (“Mr Ribbeck from Ribbeck in Havelland”) by Theodor Fontane.

Here I would like to introduce a ballad, which is especially today of great actuality. It addresses an aspect, which is of great importance in the coexistence of human beings, but which is becoming increasingly weaker in the time of exuberant consumerism and self-complacency, and runs the risk of getting lost: It is the modesty and the appreciation of the small, inconspicuous things of life.

The legend of the horse shoe

When still unknown, and low as well,

Our Lord upon the earth did dwell

And many disciples with him went

Who seldom knew what his words meant,

He was extremely fond of holding

His court in the market-place, unfolding

The highest precepts to their hearing,

With holy mouth and heart unfolding;

For man, in Heaven’s face when preaching,

Adds freedom’s strength unto his teaching!

By parables and by example,

He made each market-place a temple.

He thus in peace of mind one day

To some small town with them did stray,

Saw something glitter in the street,

A broken horseshoe lay at his feet.

He then to Peter turned and said:

“Pick up that iron in my stead.”

St. Peter out of humour was,

Having in dreams indulged because

All men on thoughts so like to dwell,

How they the world would govern well;

Here fancy revels without bounds;

On this his dearest thoughts he founds.

This treasure-trove he quite despised,

But crowned sceptre he’d have prized;

And why should he now bend his back

To put old iron in his sack.

He turned aside with outward show

As though he heard none speaking so!

The Lord, to his long-suffering true,

Himself picked up the horse’s shoe,

And of it made no further mention,

But to the town walked with intention

Of going to a blacksmith’s door,

Who gave one farthing for his store.

And now, when through the market strolling,

Cherries some one he heard extolling.

Of these he bought as few or many

As farthing buys, if it buy any,

Which he, in wonted peacefulness,

Gently within his sleeve did press.

Now out at t’other gate they’d gone

Past fields and meadows, houses none;

The road likewise of trees was bare,

The sun shone bright with ardent glare,

So that great price, in plain thus stretched,

A drink of water would have fetched.

The Lord, walking before them all,

Let unawares a cherry fall.

St. Peter ate it, then and there,

As though a golden apple it were.

He relished much the luscious fruit.

The Lord, whenever time would suit,

Another cherry forward sent,

For which St. Peter swiftly bent.

The Lord thus often and again

After the cherries made him strain.

When this had lasted quite awhile,

The Lord spoke thus with cheerful smile:

“If thou hadst stirred when first I bade thee,

More comfortable ‘twould have made thee;

Whoe’er small things too much disdains,

For smaller ones takes greater pains.”

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Taken from: The works of J. W. von Goethe,

Volume 9.djvu by George Henry Lewes, London 1901/02, p. 299.

Source: <link https: en.wikisource.org w external-link website:>en.wikisource.org/w/index.php.

German Edition: Quoted from: “Das grosse Balladenbuch”, Frankfurt without year, p. 368 ff.

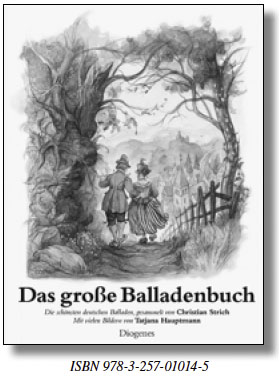

PS To this present, works are being published again and again that have collected ballads, for example, in 2016 “Das grosse Balladenbuch” with texts collected by Christian Strich, illustrated by Tatjana Hauptmann.