How are the people in Germany doing?

How are the people in Germany doing?

Elisabeth Koch, Germany

“We are doing well in Germany,” says Angela Merkel. Only now, after the election, does the question arise in the media why so many people are so dissatisfied with the situation in Germany, and with their government. There were unmistakable protests during Angela Merkel’s election campaigns, not only in the Eastern part of Germany. And for many years already, a lot of people have been voicing their dissatisfaction. They have not been taken seriously. On the contrary, citizens expressing their disagreement are pathologised: Ms Merkel talks about “fears and worries”, as if she were a psychiatrist in search of a treatment method for unreasonable patients. Rita Süssmuth, CDU, for example, said in a Swiss radio station1 that people “don’t understand” that the people who came to us as refugees were needed as workers. “We were not good enough in listening and explaining,” she says, referring to herself and her colleagues from the ivory tower, the better-knowing elite, while the citizens, on the other hand, are the ignorant masses to who everything has to be explained. Politicians promise to “pick us up” where we are, and to “take us with them”2. These people have forgotten that they have to act on our behalf, that they must ask us what we want, and how we see things. We, the citizens in the 21st century, no longer want to accept just about anything those in power present to us, or to even go so far as to consider this as the answer to everything. As enlightened people, we are very well able to observe, to get information, to recognise connections, and to draw conclusions.

“What has come over the East Germans?”

A pleasant exception was an interview in a Swiss newspaper with Petra Köpping, Saxon Minister of State (SPD). Being approached on the subject of protests in East Germany during the election appearances of Ms Merkel with the question: “What has come over the East Germans?” she explained: “Those who call, who whistle, who try to provoke are the minority. Most people are quiet, but they are not necessarily more satisfied with the situation they find themselves in.”3 This may have been received with some astonishment, since television mostly shows only those who voice their indignation loudly and noticeably. Rarely are the prudent asked; the statements that are preferred are the offensive, the drastic ones, or those which may only have been clumsily formulated. Ms Köpping pointed out that many of the East Germans were defrauded of their lives’ achievements; their professional qualifications were suddenly no longer valid, despite a good education, they lost their jobs and their reputation.

In fact, 75% of people in East Germany lost their jobs. Many people who had previously had a secure livelihood were impoverished, their professional performance suddenly counted for nothing. School education had been excellent in East Germany, especially in the fields of natural sciences and mathematics. But up to today, even former teachers with a post-doctoral degree have to earn their bread in employment below their education level. To date, according to Köpping, “people from 17 professional groups receive far too small a pension.” “But the federal government does not care about these people,” she complains. Let me give you an idea about this: The average old age pensions in Germany are 1176 euros a month, but in the east of Germany they amounted to 984 euros on average in 2015. This means that there are many who have an even smaller pension.4

Social problems also in West Germany

Also in parts of Western Germany, such as the Ruhr region and the Saarland, many people have lost their secure and qualified jobs. The fact that the unemployment rate in Germany is nevertheless so low is probably due to the fact that more and more people have to earn their livings in unsecured employment and for low wages. Today we have reached a situation where almost half of all employment contracts are only concluded for a limited period.5

Even many teachers, who once had a secure government job, now often get laid off.6 It can easily be imagined what a feeling of insecurity this produces for the family fathers and mothers concerned, what this precariousness means to them: Will I still have my work next year, can I build a house, or set up an apartment, or will we have to move again?

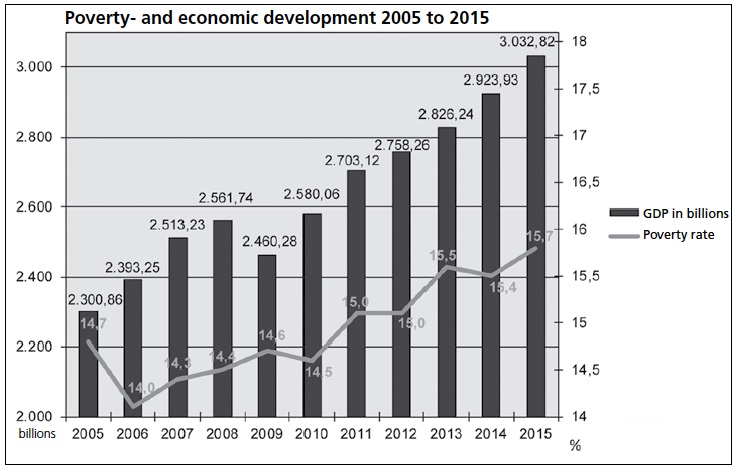

Do we have to separate in order to find work in distant places, so as to secure survival at all? Many unemployed people have to accept several jobs, work in one-euro jobs, and yet they cannot make ends meet. Even old-age pensioners or other retirees often have to look for work so as to have enough to live on. These precarious working conditions lead to an oppressive poverty for far too many people. The poverty rate in Germany is rising with the GDP, as shown in the chart. This means that there is money being earned in Germany, but by whom? Obviously, there are many losers.

Who pays? The middle class!

It is now well known that the AfD was chosen in protest by many well educated people from the middle classes. Small and medium-sized enterprises, small craft businesses, small and medium-sized manufacturing companies generate the largest portion of money in Germany, they secure our prosperity, they employ workers, they form our youth. But they have to pay more and more taxes. Someone must, for example, pay for housing, food, and clothing for the millions of refugees. Who pays for these things? This is a question that has to be asked, since it is naive to believe that a “welcome culture” would throw Manna down from the heavens. The tax load that has to be raised for this purpose is essentially provided by the middle class. Also the transfers to distressed EU member states, such as Greece, Spain, etc., are covered by resources that the middle class has to generate. On top of this, it is being hard-pressed by cheaper products and cheaper labour from abroad. The EU imposes conditions on entrepreneurs to undertake increasing bureaucratic efforts. In addition, there are sanctions against Russia, which weaken notably the European economy. “We have come to the point, where a number of federal states such as Saxony, Lower Saxony and Saxony-Anhalt are pushing for aid allotted to firms which are affected by Russia-sanctions,” writes the Handelsblatt.

In view of proposed new sanctions, Martin Wandleben, head of the Association of the German Chambers of Industry and Commerce, demands, “that Europe should en bloc react against the US plans”.7 So far, there is little to nothing to be heard of any compliance with this demand.

Farming under pressure

In the whole of this discussion, farmers are hardly present. And yet, they suffer not only under the weather, but above all under EU bureaucracy and the globalised agricultural market. Many are struggling against economic collapse. As shown by the decline in the number of farms, many have already lost this fight. But the effective agricultural area has hardly decreased in Germany since 1991. In other words, the farmers who have remained have had to enlarge their farms, and that in turn means that they are sitting on a mountain of debt incurred for the land and machinery they had to purchase. They need the machines, because the number of employees in agriculture has also declined, so that they have to do much more of the work by themselves.8 So what will farmers think of the adjuratory formula “Germany is doing better than it has done for a long while”?

Rising crime rates

The economic slump is certainly not the only reason for dissatisfaction. Other fields of politics and society are also in trouble, but discussion about them is being suppressed. First of all, of course, there is the refugee question. The great majority of people in Germany have nothing against foreigners; Germany has time and again successfully integrated immigrants, for example Poles, Italians, and Turks. Many of them now feel at home with us, and they contribute to our society and our state.

And of course we, the citizens of Germany, stand by the right of asylum: those in danger to life and limb should be allowed to come and let us help them. No German political party has ever questioned this. However, it is not acceptable to incite wars everywhere in the world, to destroy human beings’ livelihood, and then to force them to flee to Europe. What are the German government, the established parties, the media, etc., doing about these scandalous wars? Is it not a fact that more or less all of them support these wars in violations of international law, for example in Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Libya, and Syria? In many parts of Africa, riots and battles are being kept simmering; corrupt politicians are supported for lending a hand. And all this, so that natural resources such as coltan, precious stones etc. can be exploited cheaply in these countries. For a nation continually overrun by wars cannot establish a state under the rule of law, a judiciary or a police, and so it is at the mercy of the marauders. The best example is the mangled and afflicted Congo. In other countries, such as Libya, a functioning government was disempowered; structures that guaranteed labour and bread, a functioning health system, education, and law and order were all destroyed. Libya is now a “failed state”. It can no longer help solve the refugee crisis but is part of it.

This is not the place to analyse Germany’s participation in all these wars and in all this unrest. But it is immediately obvious, that the solution cannot be to invite all those who suffer from it to come to Europe. To stay with Germany, it would collapse under this burden. This is economically self-evident. But also the question how to integrate all these people would impose a great strain. It has by now become evident that only a small number of the refugees can be integrated into the labour market. But every recognised refugee has a right to an apartment, together with his family. The housing shortage in Germany was already high before so many refugees came crowding in. Now there is a frenzied building boom. Many people see that refugees often get better housing than they could pay for themselves. They also know that someone has to work and to pay for this, namely we, the citizens. It goes without saying, that this creates anger.

Many people who come here have been told that here, money grows on trees. They are supported in a demanding attitude. Many citizens realise this, and they don’t like it. Also the rising crime rates – although crimes are committed only by a minority of foreigners – from theft through robbery to rape, can no longer be concealed; people are experiencing this at close quarters, yes, they are often themselves victims. And if there is then patronising talk of “anxieties,” which “we have to allay”, it will be no surprise that this talk produces indignation. It must also be remembered that most of the refugees who come to us have no idea of our democracy and our state of law. Yet both must be supported by the inhabitants and citizens of a country, otherwise the cohesion is fragile and endangered. All this shows that world problems require solutions other than that all the disadvantaged come to Europe.

Children no longer learn enough

As some provincial parliamentary elections have shown this year, many people in this country are also dissatisfied with the fact that their children learn less and less. In North Rhine-Westphalia and Baden-Württemberg, the voters have already made the responsible state governments pay the penalty, even though the people in the West have already been getting habituated to absurd concepts for decades. In the East, education policy after the turnaround was a shock. The “Ossis”, the Easteners often underestimated by the West, are used to observing closely and to thinking historically. They are well aware that – apart from the ideological influence – education in the GDR was better, more solid, especially in science and the mathematical subjects. You don’t have to be a GDR nostalgic to realise this fact.

New patterns of family life?

The family is what is most important for most people in the new federal states. This was not different in communism. Waking up in their new freedom, they had to realise that strange patterns of family life are being propagated in the West, which they were also expected to approve. If they don’t, they incur a risk of marginalisation, exclusion, slander. By the way, there are also many people in the West who don’t agree with this, but it is not done to talk about it. The gender ideology has been superimposed on us from above. Shall we talk about how we see it, even whether we want it at all? – No chance!

In addition, the families in the new federal states still have to see their young people move to the West, because there is too little work in the East. Even many family fathers work in the West the week over. Every weekend, they go back to their family, to Saxony, to Thuringia. 327,000 commuters moved from West to East in this way in 2016.10 This is not what they had imagined as a better life. Above all, however, East Germans generally realise much more clearly than West Germans that there are bans on speaking, that there are opinions prescribed and controlled, and that there are certain red lines you may not cross. One person once said to me, “In the GDR one knew what to say and what not to say. We also knew exactly who was behind this dictate. Everything was clear and transparent. Now, after the turnaround, the bans on speaking and the pitfalls are even more complex and complicated, more inscrutable. Everything is conducted more covertly, and you can barely get an idea of who is in control.”

These are just a few of those topics that ought to be put straight on the table. There are surely a great deal more things with which citizens don’t agree, and not everyone has the same problems. But what is necessary to everyone is an open discussion. And not only that: today citizens don’t just want to be made to feel that they are taken seriously; they want to be taken seriously in plain fact. And that means: full political p articipation. There is no alternative to direct democracy. •

1 SRF, Echo der Zeit, Interview with Rita Süssmuth, 26 September 2017

2 e.g. Manuela Schwesig, SPD, in a talkshow on the election evening, 24 September 2017

3 “Luzerner Zeitung”, 20 September 2017

4 <link http: www.focus.de finanzen altersvorsorge rente kontostand durchschnittsrente_aid_19622.html>www.focus.de/finanzen/altersvorsorge/rente/kontostand/durchschnittsrente_aid_19622.html

5 cf. “Fast jeder zweite neue Arbeitsvertrag ist befristet” (“Almost every second new employment contract is fixed-term”) in Zeit online, 12 September 2017

6 cf. <link http: magazin.sofatutor.com lehrer infografik-arbeitslosigkeit-und-befristete-vertraege-bei-lehrkraeften>magazin.sofatutor.com/lehrer/2016/11/03/infografik-arbeitslosigkeit-und-befristete-vertraege-bei-lehrkraeften/

7 “Deutsche Industrie fürchtet Russlandsanktionen” (“German industry fears sanctions against Russia”). Spiegel online, 4 August 2017

8 cf. “Basisdaten der deutschen Landwirtschaft”.

<link http: www.veggiday.de landwirtschaft deutschland>www.veggiday.de/landwirtschaft/deutschland/220-landwirtschaft-deutschland-statistik.html

9 “Dossier Landwirtschaft in Deutschland. Statista.”

10 cf. <link http: www.manager-magazin.de politik deutschland pendler-fahren-immer-weitere-streckena-1077768.html>www.manager-magazin.de/politik/deutschland/pendler-fahren-immer-weitere-streckena-1077768.html

(Translation Current Concerns)