How the project Nord Stream 2 became a game of power poker

How the project Nord Stream 2 became a game of power poker

by Bruno Bandulet*

It is rare for the German government to oppose its guidelines set by Washington. When US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson visited Warsaw in January, he commented on a 9.5 billion project, that the US is not involved in financing and that is outside its remit, and which concerns the planned second gas pipeline from Russia to Germany. Tillerson characterised it as a threat to Europe’s energy security. “Like Poland, the United States is against the Nord Stream 2 pipeline,” the Secretary of State announced, adding, “our resistance is driven by our common strategic interests.” While the Poles were delighted with this American support, the Ministry of Economic Affairs in Berlin responded with the succinct statement that the project Nord Stream 2 was an entrepreneurial decision.

A pipeline that does not suit the Americans

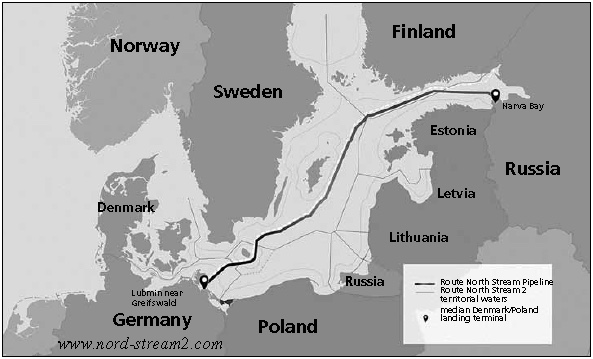

This intensifies a power struggle in which Germany and Russia are on the one side, the US, Poland and Ukraine on the other – and which is complicated by the fact that the European Commission considers it a being their department, which is in turn contested by Berlin. The Russians have already begun to encase 90,000 of the total of 200,000 pipes in concrete. At the end of January, the mining authority of Stralsund (Bergamt) approved the first 55-kilometer section of the pipeline in German territorial waters. It will run parallel to the existing Nord Stream 1 pipeline. The laying of the tubes on the 1224-kilometer route from the Russian Vyborg to Lubmin near Greifswald should start this spring.

The chances of the project being realised have increased since the negotiations over a Jamaican coalition failed in Berlin. To be sure, not only the transatlantically accommodating Greens entirely toe the American line, also Union politicians such as Norbert Röttgen and Manfred Weber, and FDP parliamentarians such as Michael Link and Nadja Hirsch oppose Nord Stream 2. Meanwhile, the United States are putting pressure on Denmark. Because the route passes through Danish territorial waters near the island of Bornholm, a Danish permit is required. This is still pending. If necessary, the pipeline will have to be laid elsewhere.

While Angela Merkel abstains from public statements, it is obvious where the sympathies of the SPD lie. Even as Minister of Economic Affairs, Sigmar Gabriel made a strong case for Nord Stream 2. Last June, he traveled to St. Petersburg as Foreign Minister, where he sat at dinner with President Putin, with representatives of the German business with the East, and with Gerhard Schröder, Chairman of Nord Stream 2, till long after midnight. This outraged Katrin Göring-Eckardt [Alliance 90/The Greens], who spoke of a “tremendous affront to the EU”.

When Russian gas first reached Germany via the Baltic Sea in September 2011, criticism was still moderate. The two tubes put into operation at that time have a capacity of 55 billion cubic meters of natural gas. They were practically working to full capacity in 2017. Nord Stream 2 can transport the same amount through two tubes – with the possibility of expansion by ten billion cubic meters. This will increase Germany’s dependence on Russian gas imports, which currently accounts for 40 per cent of German consumption.

But what does dependence mean? In a long article (Österreichische Militärische Zeitschrift 4/2017 – Austrian Military Journal), internationally interconnected energy expert Frank Umbach brings in the big guns against the new pipeline, but then the admission slips from him: “And yet, Russia is now more dependent on the European gas market than the EU is on Russian gas imports, as the EU now has a variety of gas import alternatives.”

Another one of Umbach’s statements is also true: “While Germany and the Czech Republic benefit economically from Nord Stream 2, previous transit countries such as Slovakia and Poland are more likely to be the losers.” But then he admits, “the Nord Stream 2 project is likely to strengthen the liquidity of the German gas hub as well as gas trading and could even accelerate the integration of the national gas markets in Central Europe, which might also benefit Poland and other Central Eastern European countries.”

It is, however, also correct that Nord Stream 2 will shift power relations: as long as gas flows through Poland and Ukraine, Gazprom has to rely on their co-operation. With Nord Stream 2, the Russians will free themselves from dependence. The other profiteer will be Germany. It will become the centre and economic hub for gas trading in Central Europe, albeit not necessarily the “European energy centre”, as the journal “Deutsche Wirtschafts Nachrichten” (German economic news)” speculates.

We need the gas, the Russians need the money

An insinuation also disseminated by Frank Umbach is pure invention, namely that in the future Russia will be able to blackmail its European customers. Germany, like Austria, has large gas storage facilities that would suffice for months in an emergency. They are usually replenished in the summer. In addition, Germany will continue to source Norwegian natural gas. Also Poland, which has so far imported part of its needs directly from Russia, has never been blackmailed, although relations could hardly be worse. As soon as Nord Stream 2 is in operation, Poland can be supplied at any time – via Germany as the distributor. If this is not desired, Norwegian gas and the more expensive LPG from the US are alternatives. In Poland, a pipeline to Norway is already being considered.

You can also see it this way: the Germans and the Europeans need the gas, the Russians need the money. So where is the problem? Moscow correctly complied with existing supply contracts, as early as in the Soviet-era (and even with Hitler-Germany until 1941). According to neutral observers, Kiev was complicit in the Russian-Ukrainian gas conflicts of 2006, 2009 and 2014. As soon as four instead of two pipelines pass through the Baltic, transit through Ukraine will probably be superfluous. In any case, this contract will end in 2019. Then Ukraine will lose transit fees, and the transaction of transport – as it is via the Baltic Sea – will be assuredly conflict free. It is understandable that Ukraine is reluctant to lose money and importance in terms of energy policy.

In future, Germany will need more gas than before. The production in the North German lowlands, which used to supply 20 per cent of home requirements, is declining, as is the yield of the Dutch Groningen field.

Regardless of whether one believes in the theory of controllable climate change caused by carbon dioxide or not, the federal government must be measured by its own climate goals. Despite the energy turnaround, CO2 emissions in Germany have not declined since 2009, but have remained virtually unchanged, as nuclear power has been replaced by coal-based power generation after the accident in Fukushima, Japan.

At present, around 40 per cent of electricity in Germany is generated by coal and only 13 per cent by natural gas. The burning of bituminous coal produces three times as much carbon dioxide as the use of natural gas. Once the last nuclear power plants are shut down, the gap must be closed by natural gas. Take Baden-Wuerttemberg as an example: There, two nuclear reactors that run in continuous operation, apart from the usual maintenance work, cover one third of the electricity demand. According to a decision by the Merkel government one of these must be decommissioned already in 2019, the other 2022.

To eliminate coal as well as nuclear power, and then to refrain from replacing it with natural gas, seems like an interesting variant of the 1944 Morgenthau plan. But after all, the anti-industrialists who consider this feasible also believe that energy is “renewable”. The Green Party in Germany and the European Parliament, which rejected Nord Stream 2 as early as in May 2016, are mixing dependence on America with Russophobia and energy-political illusionism, to form that kind of Europeanism that is limited to the action of constantly shifting power from nation-states to the EU Commission.

The geostrategic interest of the United States, in turn, is to sabotage any German-Russian cooperation and to confirm the concept of Russia as the enemy. The conflict with Berlin is preprogrammed. •

* The journalist and book author Dr Bruno Bandulet was i. a. managing editor at the German daily “Die Welt” and member of the editorial Quick magazine. In 1979 he established the information service Gold & Money Intelligence (G&M), which appeared until 2013. From 1995 until the end of 2008 he was editor of the background service DeutschlandBrief, which appears as a column in the magazine eigentümlich frei.

Source: DeutschlandBrief in “eigentümlich frei” No. 181 of April 2018

(Translation Current Concerns)