The founder of mountain rescue

The founder of mountain rescue

Doctor, chamois hunter, mountain guide and pioneer of accident medicine

by Heini Hofmann

The Engadin “sun doctor” became famous for his heliotherapy. Less well known is that Oscar Bernhard, affectionately known by the locals as “Il Bernard”, is also the “Father of Mountain Rescue”.

In the middle of the 19th century the challenge of mountaineering and scientific curiosity overrode the fear of the alpine world. Alpinism joined the classical spa tourism. Mountain sports, initiated by the Englishmen, soon became very popular. This brought on mountain accidents. The rescue service in the high mountains, however, was still at the very beginning.

As often in life, it was a practical genius who solved this issue, namely the well-known doctor from the Upper Engadine, Oscar Bernhard (1861–1939). He was born in Samedan as son of a pharmacist. His youth was shaped through nature and the mountains. At the age of 16, he shot his first chamois and two years later he received the mountain guide commission.

The first mountain Samaritan

At the beginning, he led a mountain practice in Samedan with a branch in the village of Pontresina. In 1895, “Il Bernard” was the driving force behind the founding of the first hospital in the Engadine. Today, it still exists in Samedan as the highest acute-care hospital in Europe and was headed by him as “directing physician” (chief physician) for twelve years. This is where he founded the sunlight therapy with which he would become world famous later on in his own clinic in St. Moritz.

As a practicing physician and surgeon, passionate high mountain hunter and commissioned mountain guide, as well as president of the Bernina section of the Swiss Alpine Club (1894–1904), Oscar Bernhard also saw the need for action in mountain rescue. Upon this realisation he immediately put it into practice.

His famous picture panels

At that time, no electronic means of communication existed. Therefore lectures and pictorial representations were used for teaching. In the winter of 1891, for example, Bernhard organised a multi-day Samaritan course for mountain guides, club members and other interested parties on “first assistance with injuries and sudden illnesses in the mountains” in Samedan in the Bernina section of the Swiss Alpine Club.

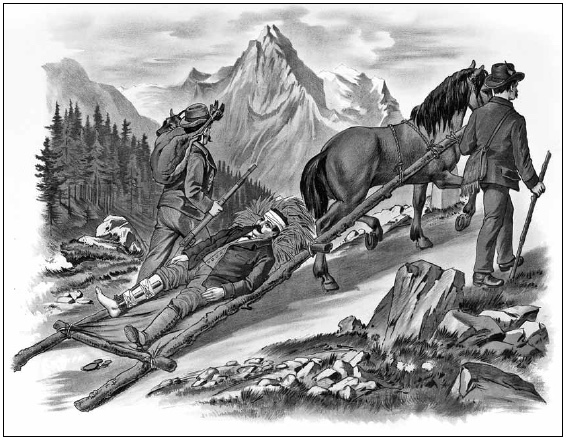

For this purpose he manufactured his 55 panels with 173 drawings on seven topics which later became famous: simple, precise and practical instructions for the Samaritan service in the mountains, both for first aid in mountain accidents as well as for transport in difficult terrain. The seriousness of the request is reflected in the over-the-top clothes of the rescuers, wearing a white shirt, gilet, hat, and necklet … – perhaps mocked at today.

Samaritan manual became a hit

These charts of which originals still exist in the cultural archives of Upper Engadine in Samedan and the Swiss “Samariterbund” in Olten, caused a sensation: They received a first class diploma and a gold medal at the trade school in Zurich and also the highest award and a gold medal one year later at the hygiene exhibition in Munich. Even the superintendent of the Swiss Army, at that time still wearing his blue uniform, described them in a militarily-sober way as “very beautiful and meritorious.”

This great response prompted Oscar Bernhard to publish a guideline in words and pictures entitled “Samaritan Service, with special regard to the conditions in the high mountains” in 1896. The “Allgemeine Fremdenblatt, St. Moritz” wrote in the 15-July-issue: “The Samariter booklet which you can carry comfortably in your pocket is highly recommend to everyone, but especially the mountaineers, tourists and guides.”

New: accident medicine in sports

Similar to the bestseller “Herbs and Weeds” by herbalist Johann Künzle, this first medical almanac for mountain guides and mountaineers had such resounding success that the Swiss Alpine Club, the German-Austrian Alpine Club, the Samaritan Association, and the Red Cross pushed the publication of a new edition. At the time when mountaineering just turned into sports and, as Bernhard himself put it, “pour hundreds of thousands into the Alpine region every year to enjoy the beautiful nature”.

This new pocket booklet for mountain guides and tourists titled “First Aid in High Mountain Accidents” appeared in its fifth edition in 1913 and was translated into Italian, French and English. As Bernhard writes in the preface, “it also took into account alpinism in winter which has developed so much since the introduction of skiing”. Thus, Oscar Bernhard was a real pioneer of accident medicine in sports.

Improvisation instead of high tech

With regard to the type of transport in the high mountains, Bernhard writes: “The very fragmented terrain with its raging streams, wild ravines, deep gorges, dense and mostly trackless forests, steep drop-offs, rocky outcrops, and wastes of ice and snow make the transport very difficult and requires extraordinary transportation and odd transport material.”

He continues: “In the mountains, mostly packsaddles are used for the pack animals, bows, and sledges to be pulled by man or beast, further carrying chairs of the reef type or the mountain basket of the northern and the carrier (Gerlo) of the southern Alps which are carried by a single man. Especially the Alpine people have become accustomed to this type of carrying and a strong man can transport a wounded or an ailing man for hours. Several carriers are better, however, who can replace one another.”

Above all, do not harm!

Bernhard’s instructions are always precise and practical. In the closing word of his first aid manual, his calm and superior manner is clearly reflected: “If you face a sudden and bad accident act calmly, deliberately and purposefully! If one or the other time it isn’t clear sure how to act, it is better to do too little rather than too much, and then perhaps something wrong! A sin of omission is always and rightly forgiven, rather than a pointless approach where someone is harmed through incorrect treatment.”

He puts it even clearer: “As generally in life and in particular when it comes to medical aid, the never-minded clever lies are dangerous. The omniscient observer of whom Billroth says their brains are like a book-box, from where in the given case they only have to take one wrong book from a wrong place to do great harm! Such people are likely to discredit the Samaritan system.”

Therefore, his paternal advice is still valid today: “So be always very careful with medical assistance, mindful of the motto based on Hippocrates, the father of medicine: Above all, do not harm! If, in a misfortune you have done well and the right thing, you are crowned the most beautiful reward, the feeling that you have done a good deed.”

A timeless credo

The final words, so to speak, include his philosophy of life: “It is nice soothing a suffering person’s pain; glorious to save him from disease and infirmity; the ultimate thing, however, which a human heart can experience is the awareness of having saved a person’s life.” This is what a doctor and philanthropist, for whom the profession is vocation and who from his own experience knows what he is speaking of! •

(Translation Current Concerns)