The “post-Mobutist” Congo: The USA is betting on Rwanda

The “post-Mobutist” Congo: The USA is betting on Rwanda

Congo – kleptocracy with no end in sight? (part 4)

by Peter Küpfer, former president of the “Association pour la Paix et l’Entente en Afrique (APEA)”

The Congo does not come to rest. Lately, our sparse media coverage of this country, being tortured for decades, revolved around the issue of the clinging of its young President Joseph Kabila to power. Similar to Mugabe in Zimbabwe, President Joseph Kabila also seems to be struggling to pave the way for a successor and election worthy of the name, in accordance with the pronouncements he made himself by the passing of the constitution. Experts of the recent development of the Congo and its many puzzling policies suspect similar reasons that also led Mugabe to cling to power: the own past and the contingency, to be summoned to the International Criminal Tribunal in The Hague for past war crimes, especially crimes against humanity. Joseph Kabila is a former comrade in arms of Rwandan President Paul Kagame, who planned, realised, and supported the so-called Congolese Rebellion (it was actually a war of aggression by the civil-war-tested armies of Rwanda, Uganda and Burundi) under the leadership of his father Laurent Désiré Kabila in 1996/97. Therein serious crimes against humanity have been committed, in particular against the eastern Congolese civilian population and the Hutu Rwandan families who fled the Congo, as explained in more detail below. Joseph Kabila, like many of today’s heads of state, has reason to cling to power. Under favour of the immunity granted by this official position, he remains protected from prosecution, as well as his political teachers and comrades Paul Kagame and Yoweri Museveni. (Museveni is the sole ruler of Uganda, who has come to power with purely military means and since then keeps it as a dictator, under the protection and the endorsement of major Western powers, above all the US and the UK).

Serious observers warn against being distracted from the real issues, particularly in the case of the Congo. These centre around the questions,

- how to explain that hundreds of thousands of Congolese civilians, particularly in the eastern provinces of the Congo, are still threatened by the turmoil of war in life and limb and have therefore been on the run for almost 25 years now;

- how to explain that the highly armed national army of the Congo is not able to identify and disarm the changing war formations in the border provinces of North- and South-Kivu (so-called militias, in reality mercenaries of Rwanda and Uganda) and bring those responsible to justice;

- how to explain that under the eyes of a UN military mission (MONUC) which has been in the country for decades, the most appalling crimes against the civilian population have taken place and continue to do so, that even the own UN-forces have been involved in the crimes;

- how to explain that members of foreign armies, which were in actual warfare with the country, held and still hold the highest positions in the country;

- how to explain that for years orders were issued and carried out by them which contained the most serious offences against humanity, i. e. mass executions of the civilian population, without the international public and the responsible institutions (United Nations) making it a matter of urgency, let alone persecuting the war criminals;

- how to explain that, although the number and the facts of the crimes committed are overwhelmingly reported in numerous internal UN documents, the perpetrators have so far had no legal action to fear (rule of lawlessness);

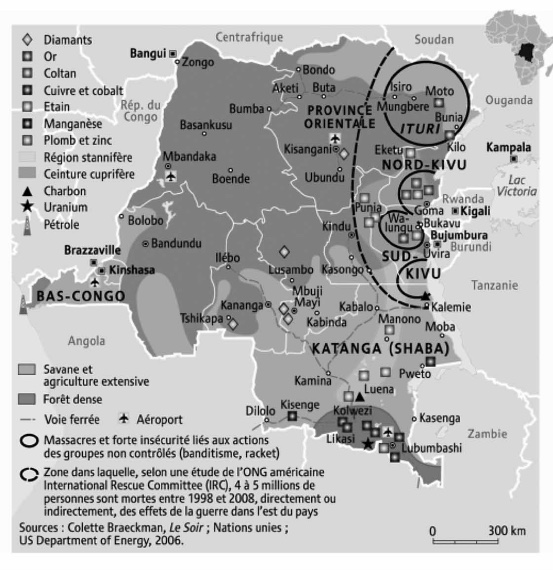

- how to explain that militias with changing names operating from Rwanda and Uganda and receiving logistical support from these states, can always do the same thing and still do it? Depopulating the entire eastern Congolese territories by their systematic terrorist acts directed against the civilian population. At the same time illegally seizing the subterranean treasures of these regions and selling them on the international black market concealing their true origin. It’s robbing the genuine owners, the poor Congolese population, which has been firmly institutionalised and internationally tolerated for decades.1 According to experts in this situation, four to five million people, most of them civilians, have died in the resource-rich eastern Congo since 1998 as a result of the direct or indirect consequences of this “indifferent war”, under the eyes of the UN contingent, which has been present there since that time and whose main mission is to protect the civilian population.

The curse of voracity for resources

The articles in this newspaper entitled “Congo – Kleptocracy without an end in sight”, which have been published sporadicly so far, have recorded the recent history of the Congo (Zaïre, later Democratic Republic of the Congo).2 They were aimed to give some fact-based hints for answering the above questions. The contributions to date have shown that the tormented giant empire in the heart of Africa has been haunted for many decades by all the destructive forces imaginable, and also where they come from and what their true motives are and were. It has been shown that its origins are essentially to be found in the fact that in eastern Congo there are resources which have attracted the greed of economic- and great powers since colonial times. Whereas rubber and fine woods were exploited around the early 1900, it was especially the immense copper deposits in Katanga, the diamond deposits in Kasai in the 20th century, as well as gold, cobalt, zinc and today the highly coveted coltan, all of which can be found in the two easternmost provinces of North and South Kivu as well as Kasai.3 In the meantime, coltan has become a much needed, rare resource. No single mobile phone, no remote-controlled missile and no drone will work anywhere in the world unless they contain components from this highly coveted ore mixture. In the two Kivu’s, the raw materials for coltan (colombo-tantalite) are present in large quantities, almost the only known mining site in the world. These two easternmost Congolese provinces, bordering Rwanda, Burundi and Uganda, were also the gateway to the recent two Congo wars (1996–2003) and their catastrophic consequences, as shown below. Since then, the apocalypse has ruled there until today for large sections of the population.

(picture keystone)

The new Africa policy of the US

It was also pointed out that the ceaseless war against the Congolese civilian population in the east must also be understood in its international geostrategic dimensions.4 The focus here is on the American so-called GHAI concept, the “Greater Horn of Africa Initiative”, which aims to create a new East African centre of power under American patronage. It should extend from Djibouti to Dar es Salaam and include the resource-rich eastern Congo. This requires the “Balkanisation” of the Congolese giant country and its weakening, a goal that the two recent Congo wars have certainly achieved. What is new is the American abandonment of the previous considerations of old diplomatic rules, interests and zones of influence, which in the case of the Congo were controlled primarily from France. In principle, this resulted in a simple formula: an “America first”, long before Trump. In Africa, too, the motto should now be the same for the United States, without any political considerations, as it has been in other parts of the world for a long time: what America benefits from is good. With the ambivalent personality of the former Ugandan resistance fighter Yoweri Museveni, the late and present autocrat of Uganda, the USA had already drawn up its own “loyalist” in the past, on which they now also rely in connection with the Congo and its weakening leader Mobutu. In particular, their long-standing military and logistical support of Museveni’s resistance movement NRA (National Resistance Army) against the former Ugandan ruler Obote helped them to achieve this. Museveni was called and praised by the USA as “African leader of a new type” after he took power in 1991. The fact, that this long term ruler (Museveni has also abolished by decree the limitation of the term of office prescribed by the constitution!) has trampled on democratic principles up to this day and exercised a one-party rule with dictatorial powers, has been and is swept under the table. With Museveni, the USA not only had an ideologically important ally, but also a geostrategically important ally, because Museveni supported the Lord’s Resistance Army, which operated from the territory of northern Uganda against the Sudanese central government, for the USA a markedly “seat of evil”. In the early 1990s, when it became clear that the Congolese dictator Mobutu, faithful to America, was increasingly weakening, personally and politically, and no longer held the reins of the giant country in his hands, things moved quickly. For the USA, it was excluded that its resource guarantor, Congo, return into the hands of patriotic and nationalist-oriented forces after Mobutu. The reorientation of the mining rights, which previously had been lucratively equipped for them, was at stake, but the military geopolitical option could not be left to chance either. For a long time, there had been a plan in the circles of the American military-industrial complex to build an anti-Islamic and America-friendly stronghold in East Africa, which would include large areas of the eastern Congo, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, and even parts of Kenya, a coherent area from Djibouti to Dar es Salaam with the corresponding hinterland, from which the Gulf of Aden and the Suez Canal could be controlled more efficiently as an important international trade and military axis. The American-inspired plan to proactively overthrow the long-standing Congolese dictator Mobutu and replace him with another guaranteed US satrap must obviously be seen in the context of the GHAI project mentioned above.5 For purely tactical reasons, the USA’s choice for such a campaign was not Uganda, but the microstate of Rwanda, from which the true reasons for the military action that has now been prepared could be better concealed. Paul Kagame, an obedient disciple of Museveni and his protecting power, the USA, regained power in Rwanda in 1994, offered the necessary guarantees, both politically and personally.

A creepy partner

The Rwandan dictator and new strongman of Rwanda, well-founded feared today by many African genuine democrats, was a political disciple of Museveni and his protecting power USA, “trained” in the field of guerrilla warfare in the American Fort Leavenworth (Kansas), a stronghold of American war experiences since the Vietnam War, involving junior military personnel for allies from regular and irregular military associations from all over the world. Paul Kagame grew up in Uganda as a child of Rwandan exiles of the Tutsi elite (they left the country when the Hutu majority, which they had traditionally suppressed, gained more political influence in Rwanda, which had previously been completely dominated by the Tutsi minority). Like many young Rwandan Tutsi in Uganda, he already served as a young soldier in Museveni’s guerrilla formation NRA (National Resistance Army) and soon drew attention to himself through his dexterity and brutality.6 In Museveni’s police state he became deputy director of the Ugandan secret (intelligence) service. Kagame was one of the founders of the Rwandan Tutsi guerrilla movement FPR (Front Patriotique Rwandais, RPF: Rwandian Patriotic Front), the military wing of the revanchist-minded exiled Tutsi minority. His goal was the military reconquest of power in Rwanda and the renewed oppression of the Hutu majority. When the Rwandan exiled Tutsi decided in 1990 to fight this battle by force, Museveni hurriedly brought Paul Kagame, who was at Fort Leavenworth for “further training” in the USA, back to Uganda, where he immediately took over the leadership of the guerrilla organisation and led the group’s four-year fight until the final victory in the summer of 1994. The war was not only fiercely fought militarily, but from the very beginning it was fought by Kagame with great propagandistic efforts and “speech conventions” to manipulate the media accompanying the fight until today. In order to better understand this aspect, we have to deal with the painful history of the long irreconcilable antagonism between the two dominant Rwandan ethnic groups, the Hutu and the Tutsi.

Rwandan Hutu and Tutsi – an ancient conflict

In the flood of literature on the mass murderous events in Rwanda in the spring of 1994, much is said about the monstrous acts committed by the Hutu majority to the Tutsi minority. These acts are not denied. They were and are a memorial of human history. What is less to be found is evidence of the atrocities committed by the Rwandan Tutsi elite, in turn, against the members of the Hutu majority who have been oppressed by them for centuries. For all serious and committed to truth witnesses provide damning evidence: There were two genocides.7 Before, during and after the April events of 1994 and their aftermath, there was also a genocide of the victorious Tutsi on the Hutu.

Little you can learn also about the historical background of the 1994 disaster. The conflict between the two Rwandan communities is as old as their common history. Like the neighbouring state of Burundi, Rwanda was a monarchy until independence in 1962. The monarchist elite, the state apparatus and the officers all came from the Tutsi population group, traditional cattle ranchers who, according to their own legend, immigrated from the north as “Nilote” in prehistoric times, quickly gaining control over the resident Hutu. They treated the Hutu, a Bantu people, with contempt and social neglect from the very beginning. Until well into the 50s of the 20th century, hardly any Hutu was admitted to higher schools and was thus excluded from civil service. A military career was also excluded for them, even though the elitist Tutsis made up only a good tenth of the total population in both Burundi and Rwanda. For them, the Hutu were born stablemen and servants, while they cultivated the nimbus as a “natural” intelligent ruling class for themselves. The first German and then Belgian colonisers of Rwanda and Burundi have in many cases shared this ideological approach to the complex ethnic situation in Rwanda and Burundi. They praised the good cooperation with the Rwandan ruling elite. Governors, influential missionaries and ethnologists of that time were also impressed by the supposedly “innate talent of the Tutsi rulers” and underestimated the potential and also the disappointment of the oppressed Hutu, for whose advancement the colonisers did little or nothing.

Swiss archbishop as contemporary witness

Archbishop André Perraudin is a completely unsuspecting and reliable witness in this respect. Perraudin, who grew up as a simple goat herder in the French-speaking Canton Valais of Switzerland, came to Rwanda as a priest missionary already in the 50s of the last century and quickly attained the highest levels of priesthood there. He became Archbishop by dedicated service to the people and the church. In his autobiography, he gave a meticulous account of the stages and relevant steps of this career in the decisive years 1956–1962 and provided them with many authentic documents.8 Unlike some of his predecessors, he recognised early the division of the Rwandan population as fatal and called the de facto exclusion of the Hutu majority from the state administration and more responsible positions as unchristian. This brought him many enemies among the Tutsi, who later accused him of anti-Tutsi racism, an absurd accusation. It may be plausible in that situation, but it is nonetheless a disastrous circumstance that, when at the independence of Rwanda the Hutu majority wished for a democratic government, and then demanded it more and more resolutely, the Tutsi practically uni-voce spoke out against a democratic participation of the Hutu in the government. In an official statement by their political leaders, the Tutsi elite wrote even in 1958, in order to justify their unwillingness to engage in dialogue with the Hutu population: “The relations between us, the Tutsi, and them, the Hutu, have always been based on a servitude relationship to this day, so there is no basis for fraternity between them and us. […] Since our kings have conquered the land of the Hutu and killed their kings and thus subjugated the Hutu – how can they now pretend to be our brothers?”9

This attitude, which diametrically contradicts the spirit of the UN Declaration of Human Rights, did not yield anything constructive. On the contrary. Jean-Pierre Chrétien describes the attitude that manifests itself here with good reason as a variety of “African racism”.10 In the eventful history of both countries, Rwanda and Burundi, where for centuries the two population groups had been deeply distrustful for similar reasons, army coups, persecutions up to mass executions, new army coups and new persecutions alternated with each other after their independence in 1959. In Rwanda, after independence (1959), Hutu’s pro rata participation in all social spheres finally became a principle, followed by persecutions of the long-standing oppressors. Many Tutsi emigrated, mostly to Uganda in 1959–61, including the Paul Kagame family, which is one of the most influential Tutsi families in Rwanda. Radical circles among the fled former Tutsi elite founded the FPR (Front Patriotique Rwandais) there and soon made preparations for a revanchist-motivated civil war in Rwanda. They wanted to regain their traditional minority rule, which as a matter of simple arithmetics could not be achieved with the democratic principle of elections, with the weapon in their hands. They were able to count on the active support of Museveni and his protector USA. The Rwandan civil war (if it was one!) was fierce and lasted from 1990 to April 1994, when the Hutu militia raged against the remaining inland Tutsi and Kagames FPR invaded Kigali as the alleged saviour from the butchery in Rwanda’s capital Kigali. What the public could not take note of (because iron silence was enforced) was the fact that the principle of extermination of the other ethnic groups (the Hutu) had long since been applied by the supposed saviours during the civil war in the so-called “liberated” areas of Rwanda itself and continued to rage in the next few years. In the new state doctrine, extensively enforced after the reinstallation of the Tutsi minority rule in Rwanda by Kagame, everyone who kept his finger on the renewed oppression of the Hutu majority was in the language of the militarily reinstalled Tutsi rulers a hired racist and mass murderer (“un génocidaire”), propagating with his criticism of the new rulers their renewed liquidation – an outrageous allegation. An argumentation and instrumentalisation of the concept of genocide which seems to be somehow familiar in other contexts.

His own fellow ethnic Tutsis victimised

This had been the moment when a cynical assassination caused the tense political situation to explode. On the evening of 6 April 1994 a Falcon-50 plane approaching Kayibandi airport (Kigali) for landing was hit and destroyed by a SAM-16 rocket. All people on board were killed. Those included no lesser figures than the incumbent President of Rwanda Juvenal Habyarimana (a Hutu aiming for reconciliation) his chief of staff plus four other close aids, as well as Cyprien Nitaryamira, the president of Burundi with two of his ministers. The plane had three French crew members. It had just returned from Tanzania where the victims attended a conference which Paul Kagame’s FPR had urged to convene. The fact that two moderate Hutu top politicians had been assassinated together with their closest collaborators, as well as the background of how they had ended up together in this plane, left no doubt for extreme Hutu circles that this had been carried out by the FPR, i.e. “the Tutsis”. Just a few hours later extreme Hutu militias attacked members of the Tutsi minority still in the country – the butchery which would go on for months had started.

Meanwhile several disturbing, independent hints11 have grown into certainty. Not only did Kagame and his followers indeed carry out the assassination of the moderate incumbent president Habyarimana (a Hutu) themselves. They were fully aware and even took it into their cynical guerrilla warfare consideration that this hit was bound to trigger again the very pogroms which moderates had warned against and the infamous Hutu militias such as the Interahamwe and their allies had prepared for months. Anything but conscience-stricken, the Tutsi strategists included those as an important cornerstone into their far-reaching war plans to regain the political power in Rwanda once and for all.

In the spring of 1994 the FPR was militarily prepared and sufficiently armed to wage an attack on Kigali. According to their strategy the decisive battle was to be supported by a state of maximal chaos in Rwanda’s capital city. Not only in Kigali but in the whole country the situation had been extremely tense for a long time. Extreme wings of the Hutu forces had been backed up by radio channels such as radio Mille Collines for years, stirring up hate propaganda and openly calling for mass murder of the Tutsi minority: In a kin liability style argument, they were blamed for ethnic cleansing, systematically carried out by victorious FPR Tutsi forces according to media reports and eye witness accounts12 in what they referred to as “liberated regions” in the west of Rwanda. In the spring of 1994 more and more people voiced their concern, including General Romeo Dallaire, commander of the Canadian UN unit MINUAR stationed in Kigali, who informed UN Secretary-General Boutros-Ghali that extremist Hutu groups had not only installed weapon depots throughout the Rwandan capital Kigali and the whole region, but had also compiled death lists with names of ethnic Tutsis. They were ready to strike any moment. Nobody knew that better than Kagame and his secret service.

From all what we know today about the underlying strategy regarding the Congo, the Rwandan civil war 1990–1994 and the double genocides appear to have been just the prelude of even more cruel events in hindsight, eventually leading to a reorientation of the political landscape in Central Africa. Retrospectively, the Rwandan FPR and their chief strategist and leader Paul Kagame not only approvingly accepted the genocide of the Tutsi minority by extremist Hutu organisations, but indeed triggered it by the assassination coup of 6 April and instrumentalised it as a propagandistic framework to re-establish minority Tutsi rule in Rwanda. For solely strategic reasons, the Tutsi chief strategist betrayed his fellow Tutsis – those who had stayed at their homes in Rwanda – to be victimised.

For simple technical reasons suggesting the assistance of at least one foreign power (and their intelligence services), this perfidious assassination, which triggered the mass murders in Rwanda, has never been officially investigated to this day, nor was anybody punished for it. The chief prosecutor of the UN special tribunal for the investigation of war crimes in Rwanda, Swiss attorney Carla del Ponte, describes in her autobiography which pressures she had to face when she made attempts to include the FPR and Paul Kagame, by now incumbent president of Rwanda, into her investigations13. It did not take long for her to be removed from her position as chief prosecutor regarding Rwandan affairs and to be replaced by somebody else. More facts and information on the international chess-board moves in connection with the never-ending Congo wars will be provided in future articles of this series. •

1 cf. also Bucyalimwe Mararo, Stanislas. The Democratic Republic of Congo – amidst the East African storm, in: Current Concerns, No. 20/21 of 14 August 2015, where the author explains in all clarity the new African policy of America and the strategic concept of a “Greater East Congo”, the Greater Horn of Africa Initiative GHAI, which is often referred to in this context; as well as Küpfer, Peter. (<link en numbers no-2021-14-august-2015>www.zeit-fragen.ch/en/numbers/2015/no-2021-14-august-2015/the-democratic-republic-of-congo-amidst-the-east-african-storm.html) The killing in eastern Congo continues – while diplomacy takes its time, in: Current Concerns No. 15/16 of December 2008

2 Part 1: Current Concerns No. 32/33 of 31.12.2015: “50 years ago Mobutu Sese Seko revolted in the Congo, A never-ending Kleptocracy? (part 1) ”[<link en numbers no-3233-31-december-2015>www.zeit-fragen.ch/en/numbers/2015/no-3233-31-december-2015/50-years-ago-mobutu-sese-seko-revolted-in-the-congo-part-1.html]; part 2: Current Concerns No. 6 of 22.3.2016: “50 years ago Mobutu Sese Seko revolted in the Congo – A never ending Kleptocracy?” [<link en ausgaben nr-6-15-maerz-2016 vor-50-jahren-putschte-im-kongo-mobutu-sese-seko-kleptokratie-ohne-ende.html>www.zeit-fragen.ch/en/ausgaben/2016/nr-6-15-maerz-2016/vor-50-jahren-putschte-im-kongo-mobutu-sese-seko-kleptokratie-ohne-ende.html]; part 3: Current Concerns No. 2 of 24.1.2017: “The “new” Africa policy of the West and the Congo, Kleptocracy without end? Infinite Congo Troubles” [<link en editions no-2-23-janvier-2017 la-nouvelle-politique-africaine-de-loccident-face-au-congo-kleptocratie-sans-fin.html>www.zeit-fragen.ch/en/editions/2017/no-2-23-janvier-2017/la-nouvelle-politique-africaine-de-loccident-face-au-congo-kleptocratie-sans-fin.html]

3 See map: Baracyetse, Pierre. L’ Enjeu Géopolitique des Transnational Minières au Congo, Dossier SOS Rwanda-Burundi, Belgium 1999, p. 36

4 The emigrated Congolese historian Stanislas Bucyalimwe Mararo, a long-standing researcher and employee at the Africa of the Great Lakes Research Institute at the University of Antwerp, has provided relevant evidence in various publications with reference to decisive facts. The destabilisation of the Congo and the attempt to redraw its borders are described by Bucyalimwe as the “Balkanisation” of the Congo wanted by the Americans. Nothing less than the lucrative and resource-rich eastern Congo is to be separated from the rest of the country, redrawing the map of East Africa according to the geostrategic concepts of the American military-industrial complex and its political mouthpieces. See among others Bucyalimwe Mararo, Stanislas. Manoeuvering for Ethnic Hegemony. A thorny issue in the North Kivu Peace Process, Brussels (Editions Scribe) 2014, foreword and passim. The humiliations to which the Congo has recently been subjected obviously have the objective of further disintegrating the state from within.

5 This strategic reorientation of the United States, which focused on the Rwandan civil war and the warlike conquest of eastern Congo, is precisely documented in his revealing book by the long-standing personal advisor Mobutus, Honoré Ngbanda Nzambo, who is now living in exile on the basis of a genuine democratic reorientation of the Congo, naming the main politicans responsible for this, including the democratic “bearer of hope” Jimmy Charter: Honoré Ngbanda Nzambo. Crimes organisés en Afrique centrale. Révélations sur les réseaux rwandais et occidentaux, Paris (Editions Duboiris), 2004, ISBN 2-951159-9-6. See also Chossudovsky, M.. Le génocide économique au Rwanda, in: Mondialisation de la pauvreté et nouvel ordre mondial, Montréal 2004, p. 134–135; Bucyalimwe Mararo, Stanislas. Manoeuvring for Ethnical Hegemony. A thorny issue in the North Kivu Peace Process, Brussels 2014 (Editions Scribe), vol. I, pp. 13. and passim.

6 Onana, Charles. Les secrets du génocide rwandais, Paris, Ed. Duboiris, 2002, pp. 22.

7 cf. the detailed testimonies of a former FPR officer who followed the corresponding actions as a contemporary witness and participant and later meticulously documented them: Ruzibiza, Abdul Joshua. Rwanda. L’ Histoire secrète, Paris (Editions du Panama) 2005, pp. 334-347. He would have been one of the main witnesses in the failed trial against the Rwandan war criminals in the wake of today’s Rwandan President Paul Kagame. With reference to the Belgian Africa researcher Filip Reyntjens (African Institute of the University of Antwerp), the German Rwanda specialist Helmut Strizek confirms that the FPR itself (between 7 April and 9 April 1994) murdered or had murdered 121 Hutu members, mainly intellectuals, in the district of Remera on the basis of existing own lists (Strizek, 1998, p. 218, note 3).

8 Perraudin, André. Un Evêque au Rwanda. Témoignage, St. Maurice (Switzerland) 2003

9 Strizek, Helmut. Congo/Zaïre-Rwanda-Burundi – Stabilität durch erneute Militärherrschaft? Munich/Cologne/London (Weltforum-Verlag) 1998, p. 60

10 Chrétien, Jean-Pierre. L’ Afrique des Grands Lacs. Deux mille ans d’Histoire. Paris (Aubians) 2000, p. 278, Chrétien, who derives the increase in tensions between Hutu and Tutsi meticulously historically, confirms the alienation of the two ethnic groups, in part statistically (ibid., p. 249). In his monumental study on the disastrous effects of this racism on the eastern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo, the emigrated Congolese historian Stanislas Bucyalimwe Mararo (who comes from the North Kivu), however, regrets the one-sided view of the much-cited connoisseur of the history of the countries in the African Great Lakes region, who, following the “official” reading here pushes the fanaticism mainly to Hutu and has a tendency to embellish the equally sinister and in their effects disastrous racially motivated activity of the Tutsi (Bucyalimwe Mararo, Stanislas. Manoeuvring for Ethnic Hegemony. A thorny issue in the North Kivu Peace Process, Brussels (Editions Scribe) 2014, vol. 2, pp. 168.

11 Numerous publications confirm these facts. Four of them should be mentioned here: Onana, Charles. Les Secrets du Génocide Rwandais, Paris, (Ed. Duboiris) 2002; Onana,Charles: Ces Tueurs Tutsi. Paris (Ed. Duboiris),2009, pp. 47 and passim; Ruzibiza, Abdul Joshua, Rwanda. Histoire Secrète, Paris (Ed. du Panama) 2005, p. 237ff.); Ngbanda Nzambo, Honoré. Crimes organisés en Afrique Centrale. Révélations sur les réseaux rwandais et occidentaux, Paris (Ed. Duboiris) 2004, pp. 119.

12 Documented in detail by Ruzibiza, Abdul Joshua, cited above, listing dates and names of responsible FPR commanders. Honoré Ngbanda and Charles Onana, as well as many human rights organisations including the East Congolese Groupe Jerome who get their information from reliable sources on the ground, bear testimony to the RPF pogroms against Hutu civilians in the occupied territories.

13 Del Ponte, Carla. Im Namen der Anklage. Meine Jagd auf Kriegsverbrecher und die Suche nach Gerechtigkeit, 2009 (Fischer Taschenbuch-Ausgabe), p. 302–314