“Painting without ceremony”

“Painting without ceremony”

Gabriele Münter art exhibition in Munich

by Gisela Schlatterbeck-Kersten and Ingo Kersten

An exhibition bag with a brightly coloured portrait of a woman induced us to travel to the Lenbachhaus in Munich, where we arrived on a sunny Sunday in January. The trip from Lake Constance to Munich, to see the large exhibition of works by Gabriele Münter (1877–1962), proved to be worthwhile indeed. There was a treasure of wonderfully beautiful colourful pictures to discover, with very attractive, daring colour compositions, which always surprise the admirer all over again.

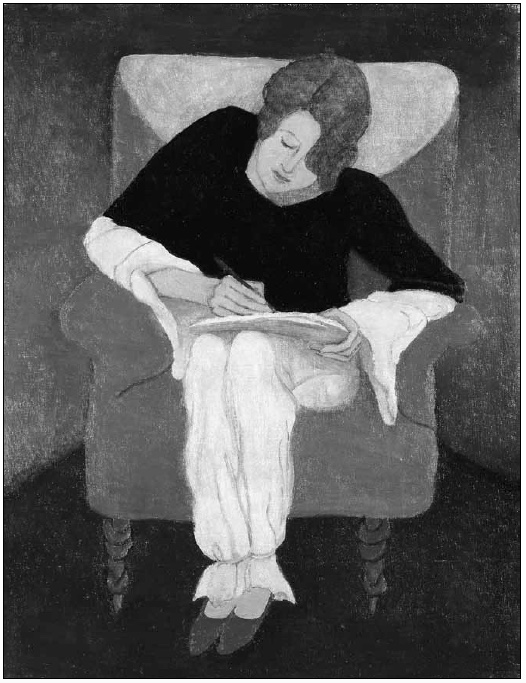

(Bild Beate Obermann. Lenbachhaus und Kunstbau München)

The exhibition impressed us for a variety of reasons. We had already got acquainted with Gabriele Münter’s work as part of that of the expressionists in our Munich student days in the sixties, when we visited the former Lenbachpalais; but now we realised that this had only been a small part of her work.

The once tranquilly intimate Lenbachhaus, a painter’s villa, has now become a large modern exhibition building, with an extra room in an abandoned subterranean underground station, which makes a spacious and generous impression as an exhibition hall with interim installations. And this space is effortlessly filled by the work of Gabriele Münter.

The exhibition is not chronological but theme-centred. This is new and consistent for the work of Münter, which did not develop in chronological stages. Rather one can say that, regardless of her frequent relocations and stays abroad, Gabriele Münter kept her to way of working, varied her motifs, transposed them into other techniques or repeated almost identical versions after some years had passed.

The 10 sections, in which the exhibition is divided, are arranged according to themes that show images from different creative periods. She also appropriated a variety of techniques in the course of her life.

She began drawing portraits at the age of 14. When she was 21, she went to America for two years (1898–1900), and photographed people, landscapes, seasons and portraits. Photographs remained inspiration and basis for her paintings throughout her life.

Back in Germany in 1902, she attended a woodcut course in Munich, and time and again created coloured variations of her prints, of portraits or landscapes, such as the series “Toys” from 1908.

Later in Murnau (Allgäu) she became familiar with the glass paintings made in small workshops there and also experimented with this technique. The outlines of the motifs are painted laterally reversed on the glass and then filled with colours. When the glass is turned around, the colours then shine through it. In many later pictures the strong dark outlines and the rich colour surfaces remind one of paintings behind glass like these.

Work and technology

Already in America, she photographed and sketched her relatives as they worked in the fields as well as railway constructions and locomotives. In 1911 the picture “Ruhrgebiet II” was created, showing an industrial landscape. But she paid particular attention to construction work. When in 1935–1937, a railway line and a road to Garmisch-Partenkirchen (Olympiastrasse) were built in front of her house in Murnau, she was fascinated by one powerful, smoking machine, the excavator. She often spent half a day there, talking to the workers. Several times the monster, the excavator, was the centre of an image. Among others was created the picture named “The Blue Excavator”.

In the course of her life, she witnessed many style changes that inspired her to seek new expressive possibilities. When in the twenties some painters turned to a nearly photographic-puristic style of painting, which was intended to depict objects and people in a cool and matter-of-fact manner, without showing traces of the working process, she took up this manner of painting. But in what way! The 1929 portrait of the writing woman in the easy chair showed her painting skills with its great refinement, delicate yet determined. Although the shapes and colour areas are sharply outlined, the delicately and materially painted pyjama bottoms and the red shoes are by no means “factual”.

In the last exhibition section on dealing with her handling of abstraction, there are examples from two working phases. The first of them, dating from the years 1914/1915, was based on a stimulus given by nature and gradually became, with every picture, more and more abstract. Later, as a 70-year-old, she once again painted some nonrepresentational pictures (they are studies with well-defined, very colourful forms). She calls them bagatelles, as if she wanted this phase of her painting not to be taken too seriously.

At some places in the exhibition, you are suddenly captured by moving pictures – film clips. The medium of film, you learn, was stimulation and relaxation at the same time for Gabriele Münter.

After visiting the exhibition, it became clear to us that the work of Gabriele Münter had effectively only been known to us until the beginning of the First World War and the departure of Wassily Kandinsky and that we had really only known her as a student and the partner of Kandinsky and as a member of the group Blauer Reiter. So, like G. Knapp in the “Süddeutsche Zeitung”, we asked ourselves: “How was it possible for such an important part of recent German art history, such a multifaceted artistic work dating from the first half of the 20th century, to be almost completely denied to the public to this day?” That was a question that concerned us very much. We ourselves witnessed that in the fifties abstract art was almost exclusively promoted at the academies, strongly inspired from Paris. But in the sixties, New York became the capital of the art avant-garde, and as a result we experienced the Cultural Revolution of the ‘68s in Europe, the so-called student’s riots. These challenged values and traditions throughout European cultural life, and even went so far as to destroy them, which was, especially in Germany, strongly in the interest of some US circles. In this context, the artist Gabriele Münter’s oeuvre was no longer in the spirit of the contemporary trend.

Therefore great credit must be given to the curators to have developed this exhibition. A large part of the 140 paintings has never been shown to the public, or was shown for the last time decades ago. It comes from the estate of the artist and was supplemented by rarely issued loans.

We wish this exhibition a resounding response! •

Dates of the exhibition:

Lehnbachhaus, Munich, until 8 April 2018 (then in Denmark), then in the Museum Ludwig in Cologne from 15 September 2018 to 13 January 2019

(Translation Current Concerns)