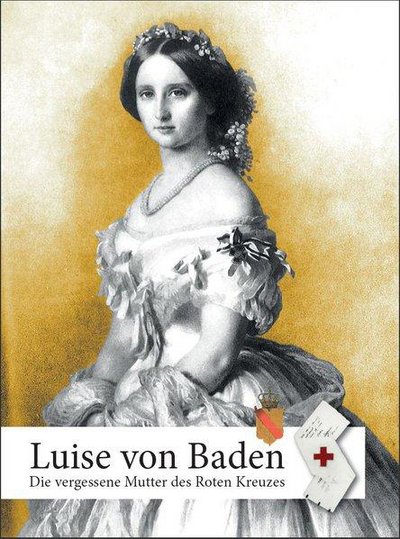

“Louise of Baden – the forgotten mother of the Red Cross”

“Louise of Baden – the forgotten mother of the Red Cross”

Little attention for contributions of German culture

by Moritz Nestor

The Luisenstreet in Baden-Baden, named after Grand Duchess Louise of Baden, leads along the narrow river Oos to the city centre of Baden-Baden. In the sixties of the last century it belonged to my daily way to school from the west town to the actual Baden-Baden. “Mer gehe in d’Schdad” [“we are going to town”] as was said of this cosmopolitan spa city, which we know from Dostoyevsky’s novella The Gambler. Already the Romans appreciated the hot springs of the Oos valley coming from 2000 metres deep. Here, about 70 AD, they established the military base Aquae with a pronounced bathing culture. This is where Trajan and Hadrian bathed. Above the ancient ruins, the 19th century created magnificent baths in the style of the time. Among others the Augusta-Bath, named after Louise’s mother, Augusta von Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach. At the Augustaplatz, named after her, we got off to get to the Markgraf-Ludwig-Grammar School.

We “westeners”, however, lived in a different world from those “in dr’Schdad” (“in town”). In the fifties it still had a semi-rural character with three farms. At the time, I knew neither the Grand Duchess Louise of Baden through whose street, named after her, I cycled daily, nor the Baden Women’s Association, founded by her in 1859.

Today, the historiography of the Red Cross no longer mentions the Grand Duchy Baden, the Baden Women’s Association and the Grand Ducal couple Frederick I. Grand Duke of Baden and Luise of Prussia neither their contribution to the founding of the Red Cross. The Baden Red Cross, however, upholds the memory of Louise and awards the “Order of Merit Grand Duchess Louise of Baden” as the highest award. In numerous rooms of state and district associations of the German Red Cross her picture still hangs next to Henry Dunants.

In 2012, with his book “Louise of Baden. The Forgotten Mother of the Red Cross”, Kurt Bickel has earned the great merit of having rescued the humane work of Grand Duchess Louise from oblivion. Reading it is a wonderful private lesson that allows one to get to know another, unjustly forgotten side not only of my hometown, but also of Prussia and the Red Cross.

Reading Bickel’s book, Louise’s Baden Women’s Association turned out to be the oldest Red Cross sorority in Germany. In 1862 Dunant writes,”A memory of Solferino”. The Red Cross is founded in 1864. The Baden Women’s Association, founded already in 1859 by Louise of Baden, can thus be regarded the oldest Red Cross institution in the world.

In 1838, Louise was born as a Prussian princess of the House of Hohenzollern in Berlin. Her father William is the “Prince of Grapeshot”, who is still hated by Baden historians and who in 1848/49 bloodily suppressed the Baden revolution with the conquest of Rastatt near Baden-Baden. In 1871, he is crowned Prussian King and further more in 1871, in the conquered Versailles, he is crowned Emperor William I of the newly founded second German Empire.

Alfred Krupp, the armorer of the German Empire, the cannon king with the double range steel guns, the prince of the newly emerging industrial nobility and general of an army of thousands of workers, was closer to the imperial “Prince of Grapeshot” than Henry Dunant with the likewise new ‘invention’ of humanity,” reports Bickel. To William the Red Cross ideas of his daughter always remained alien.

Louise’s mother Augusta, however, the later German Empress, a born princess of Saxony-Weimar, had grown up in the Weimar of German classicism and cultivated active contact with Goethe as a child and young woman. Louise’s grandmother was the Russian Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna, Grand Duchess of Saxony-Weimar. She “had what we call the ‘Russian soul’ or the ‘big heart’, at least character traits that were contrary to Prussian discipline. [...] Grandmother, mother and granddaughter were of high classical education and influenced by the ancient Greek ideal of the incorporation of beauty and the Good [...]. Throughout their lives they felt obliged to the idea of benefaction, charity, Christian charity in practice, and the Samaritan work incumbent upon women.”

Already in 1814 Maria Pavlovna, Louise’s model, founded the first German women’s association to alleviate the adversities of war: the Weimar Patriotic Women’s Institute. In 1817 it expanded into the Patriotic Institute of Women’s Associations in the Grand Duchy of Saxony-Weimar-Eisenach, a forerunner of the later German Red Cross foundations. Louise’s mother Augusta becomes the pioneer of social welfare institutions, nursing and public health care. “The women’s associations of Pavlovna and above all the outstanding social commitment of Augusta have decisively shaped the social history of the 19th century”, Bickel judges and quotes Henry Dunant: “Queen Augusta had given a powerful stimulus through her personal activity [...]. She was the first international Samaritan in Germany”.

When Louise was 10 years old, she moves to Koblenz, where she lives until the age of 18. Her father is Prussian Governor General for the Rhine Province, Rhineland and Westphalia. Mother Augusta is in opposition to militaristic Prussian politics and gathers “a large number of progressive and clerical spirits around her in Koblenz”. She introduces her daughter Louise to the task of caring for the poor and the sick. Augusta is a follower of the religious peace movement of the 19th century and is close to the liberal ideas of the Enlightenment. She rejects the military armament of Prussia. She rightly sees in it the preparations for the 1864 war against Denmark and 1866 against Austria. Augusta also wants a German nation state, but only with “moral conquests”. She abhors Bismarck’s policy of “blood and iron”, for which he publicly scolds her an “old frigate”.

Since 1850 Louise and mother Augusta have been staying in Baden-Baden every summer. Here, in 1855, the 18-year-old falls in love with the later Grand Duke Frederick of Baden. They married in 1856. Louise shares government affairs with her liberal-minded husband. The Prussian Louise slowly gains the recognition of the Baden population through her social and charitable commitment. In 1870, after 13 years of social commitment, a secret cabinet is set up for 31-year-old Luise, which is part of the government apparatus and with which she administers an aid fund.

Louise’ humane life’s oeuvre is the founding of the Baden Women’s Association in 1859. From 1853 to 1856, one of the most horrific wars that Europe has ever experienced rages: the Crimean War. “For the first time, the war showed itself in its new, industrial form” and Europe experienced its “first Verdun”.1 All of Europe is shaken at the horror of the press reports. The mortality rate is over 40%! But one is touched though by the English nurse Florence Nightingale, who with 38 nurses is fighting the misery in 4 large military hospitals.

In May 1859, touched by this, 18 citizens of Fribourg and Karlsruhe suggest the establishment of an aid fund, and Louise makes herself available. In June, she writes a memorandum to the state government in support of “persons in need” because of war. The existing women’s associations in Karlsruhe merged with all other women’s associations in Baden to form the newly founded women’s association of Baden. It is assigned the patriotic task of “being able to help people in need in the event of war as well as wounded and sick military personnel”. The statute reads: “The association serves to support those in need as a result of war threats or war as well as the provision for wounded and sick military personnel”. The core of Dunant’s later Red Cross idea is pre-formulated here.

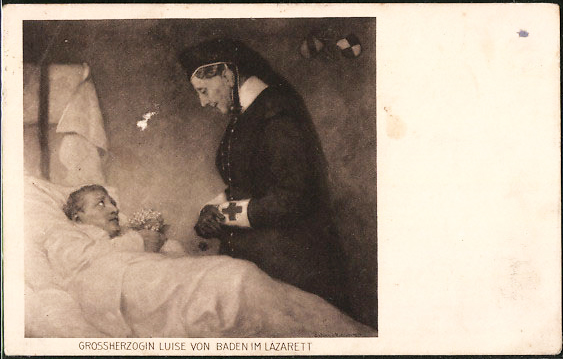

On 24 June 1859, two weeks after the founding of the Baden Women’s Association, Henry Dunant witnessed the horrific battle of Solferino, and the history of the founding of the Red Cross took its familiar course.In times of peace, the Baden Women’s Association subsequently assumed extensive social responsibilities. In 1870 there were 2.1 per cent and in 1909, 15.3 of all adult Baden women organised in it.In 1863 Frederick I. of Baden was one of the first princes in Europe to receive Dunant’s memorandum A Memory of Solferino. In September 1863 Dunant meets Louise and her mother, Queen Augusta, in Baden-Baden. Most likely it was about the mentioned core purpose of the association of the Baden Women’s Association, which was presented Henry Dunant’s “Committee of Five” for its planning of the Red Cross. Augusta must have worked energetically on the Prussian Minister of War, whereupon Dunant’s idea of making the planned Red Cross helpers neutral in wartime, was received enthusiastically. Like me, other Germans may be taken back by the forgotten pages of history of it’s own “specific German culture”. It is worthwhile to rediscover and preserve the other sides of one’s own people and its history, despite the cannon thunder of contemporary historical clashes. For the urgent questions about a more peaceful future for our descendants, there are still many unearthed treasures in the history of our people. •

1 Fesser, Gerd. Europe’s first Verdun. In: Die Zeit from 7 August 2003