The culture of cooperative ethics and its way of life

To the new publication “Cooperative economising – modern construction. Architecture of Cooperatives in Saxony”

by Urs Knoblauch, culture journalist, Fruthwilen

In general, too little is known about the enormous expansion of cooperative systems worldwide. With its more than 21 million members especially in Germany, it deserves more attention in society and in educational institutions.

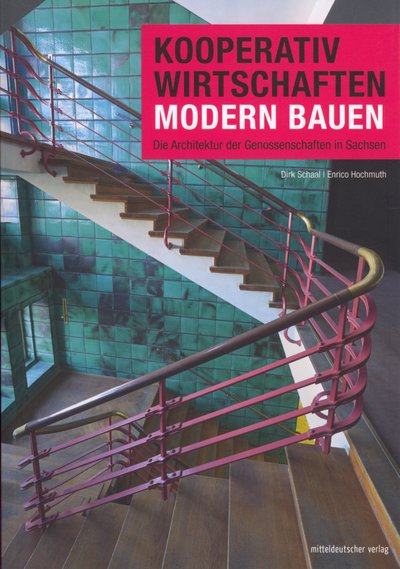

This was the starting point of the publication project of the “Hochschule für Technik, Wirtschaft und Kultur Leipzig” (Dresden University of Applied Sciences). Since museum and exhibition design as well as museum education enjoy great popularity and investment, the idea was born to establish an interdisciplinary course of studies in “museum education”. The richly illustrated publication “Cooperative economising – modern construction. The Architecture of Cooperatives in Saxony”) combines modern architectural development with the cooperative idea. The aim is to convey the valuable way of life of cooperatives to students and the younger generation. According to the authors and Leipzig university lecturers Dirk Schaal and Enrico Hochmuth, “architecture as a cultural form of expression of the cooperative idea has rarely been addressed”.

Especially to celebrate the anniversary of the founding of the Bauhaus movement, an important topic in the context of the cooperative is addressed. The concerns of the Bauhaus ought not be reduced to formal criteria, just as the cooperatives entail more than just an economic model but form a future-oriented ethical way of life. These original concerns must be ensured with care. They should always be reflected against the background of human scientific findings and their political goals.

On architecture as a cultural form of expression of the cooperative idea

The authors of the work succeed in presenting a synopsis of architecture and cooperative idea in the Saxony region with its impressive industrial culture. Dirk Schaal worked as a science archivist and is currently head of the Koordinierungsstelle Sächsische Industriekultur (Coordination Office of Saxon Industrial Culture). Dr Enrico Hochmuth is an architectural historian and was, for many years, an active leading curator of the Schultze-Delitzsch-Haus (Schultze-Delitzsch-House). The German Museum of Cooperatives (Deutsches Genossenschaftsmuseum). He has worked for the successful inclusion of the German cooperative system on Unesco’s list of intangible cultural heritage together with Dietmar Berger, the initiator. Hochmuth works as an event and project manager at the University’s Media Faculty. In 2017, the “1st Museum Education Colloquium” with new research results was held with great success. Dr Stefan W. Krieg-von Hösslin, architectural historian and city conservator of Leipzig (monuments) also contributed to the work.

In the first part of the publication, the authors present the theoretical and historical references to industrialisation and the forward-looking social cooperative system. In the second part, 16 impressive cooperative buildings are presented, mostly in Saxony and in the style of the once again popular Bauhaus architecture. “This is the first time that outstanding and predominantly listed sites belonging to the architecture of the reform movement and classical modernism have been compiled here. A broad spectrum is represented with housing cooperatives, the large consumer cooperatives in Leipzig and Dresden as well as the nationally significant production facilities of the central purchasing cooperatives GEG with buildings in Riesa, Frankenberg or Chemnitz”. (flap text)

Architecture as a mirror of certain concepts of man and models of society

The diverse language of form, function and practical application of the cooperative form of working and living of the industrial heritage is impressive. Dirk Schaal writes: “The cooperative movement is part of our industrial culture. In the social, religious and national conflicts of the 19th century, it helped to shape the cultural transformation of Germany into a modern industrial country and met central questions of industrial society”. (p. 8)

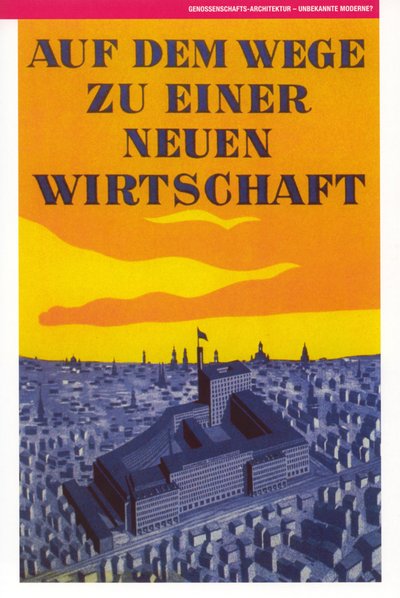

The cooperative idea was propagated with well-designed posters, equipment and furniture. It was not only a matter of providing affordable food or affordable housing, “but also of creating working conditions in one’s own company or creating social housing conditions which noticeably improved the situation of the middle and lower income groups for the individual” (p. 8). The functional, powerful and dominant factory buildings that were built already before the First World War were intended to symbolise the new basic attitude of cooperative life in a “hostile environment” (p. 21).

In addition to the acrimonious economic and political debates, there were also ideological, political and formal differences among the architects. At that time, the traditional “Heimatschutzstil” (style of listed buildings), popular among the population, dominated. With the “Neues Bauen” (“New Construction”) of modernity and the new industrial technologies and materials, however, a “new man” was also propagated. According to Dirk Schaal, “The design of the settlements according to the cooperative principles of the community was aimed at the ‘New Man’ propagated by the cooperatives” (p. 32). This should make more reference to the social nature of man, the political movements and the democratisation of social coexistence. This year’s Bauhaus anniversary was conceived to increasingly focus on the original concerns of the interdisciplinary interaction of the social Bauhaus idea of modernity but also facilitate critical reflections. It is not about a modern formalism, as often seen today, but about aesthetics and ethics of the individual and the common good.

Especially in the first third of the 20th century, modern design principles became more and more accepted not only in Germany, but also in other European countries. “In addition to renowned architects – such as Walter Gropius, for Konsum Dessau-Törten or Max Taut, for a department store of the Konsumgenossenschaft (consumer cooperative-society) Berlin und Umgebung (and surroundings) – a predominant number of architects are to be found here who had adopted the principles of modern construction in the course of their professional practice or had already aquired them during their training.” (p. 32)

Anyone familiar with the historic region of Saxony and the surrounding area will be amazed by the great economic, cultural and social achievements and buildings. They are partly documented in the book. With the dissolution of the GDR, valuable cultural assets were also endangered. Despite the considerable rescue of the building fabric and its reconstruction, there is still a great deal of work to be done.

Hermann Schulze-Delitzsch and Wilhelm Raiffeisen

Enrico Hochmuth graphically introduces the topic “Cooperatives in Saxony” using the example of the Hermann Schulze Delitzsch Monument on Marienplatz in Delitzsch, designed in 1891 by sculptor Erwin Weissenfels. Its changeful history, from the melting down for the war economy during the Second World War to the 1950 replica by the sculptor Max Alfred Brumme and the removal to another location for a monument of the first president of the GDR as well as the return of the restored monument to its original location in 1991, exemplifies the political dealings with the cooperative idea.

ISBN 978 3 96311 051 1

“Germany’s first successful commercial cooperative was founded in 1849 by Hermann Schulze-Delitzsch (1808–1883) with 57 shoemakers in Delitzsch. With their Association of Basic Commodities, the tradesmen are able to arrange the purchase of basic commodities, tools, machines and other commodities at a reduced rate and to later take the sale of their products into their own hands. The liberal Schulze-Delitzsch saw this as an opportunity to advance the situation of the needy tradesmen and petty traders. “In addition to the economic pressure exerted by industrialisation, the transformation from a corporative to a bourgeois society was also associated with the loss of traditional life contexts and social networks.” (p. 34) 1889, the experiences of Schulze-Delitzsch’s initiated mergers and production cooperatives were taken into account in a ground-breaking law on cooperatives and led to a “founding boom of cooperatives in the German states” (p. 34).

In this context, the beneficial work of Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen (1818–1888), proceeding from the Westerwald, must also be pointed out. Sustained by deep benevolence, social connectedness with the people, Christian ethics as well as trust in the charitable human nature, he founded the cooperative, local “Raiffeisenkassen”. (Raiffeisen Banks) His central idea: “We are only strong in communion”, and with the three “selves” of the cooperative, self-help, self-governance and self-responsibility, the principle of subsidiarity (responsibility from below, built up by each individual human being) is also included. Thus, democratic participation should be made possible and secured. Each cooperative member has a voice in the decisions, regardless of his social situation and the number of cooperative-shares. The “rural credit societies and common warehouses initiated by Raiffeisen experienced a marked expansion with the creation of rural purchasing and sales cooperatives by Wilhelm Haas” (p. 37).

Closely linked to this are the credit cooperatives, which were initially set up with “advance disbursement associations” along the lines of the rural credit cooperative established in Denmark in 1846 and which in many countries also promoted the establishment of People’s banks.

With the aid of examples, Enrico Hochmuth illustrates the great success of the pioneers Hermann Schulze-Delitzsch and Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen. “In a first wave of foundations about one hundred productive cooperatives of craftsmen in various fields emerged throughout Germany between 1860 and 1889.”One such association is the mill and bakery Bärenhecke Raiffeisen-Genossenschaft e.G. in Bärenhecke, in the eastern foothills of the Erz Mountains. Today, the historic mill and bakery are equally a cooperative business and a technical monument to visit. On 20 August 1898, the company was founded by 26 local farmers as Cooperative for Milling, Baking and Storage Warehousing, Oberes Müglitztal e.G.m.b.H., in order to take into their own hands the grain processing right up to the end product itself. The water mill on the Müglitz acquired by the cooperative obrained a link to a light railway and started production as early as 1899. By 1913, 300 members had joined the company. To support the farmers, especially in the years of crises’, the cooperative set up a bank department which existed until 1993. In 1995, in order to preserve and promote the monument, a “Förderverein Technisches Denkmal Getreidemühle Bärenhecke e.V.” (Foundation Technical Monument Grain Mill) was founded. (p. 34) With additional examples, the author presents the successful cooperative precision clock factory Glashütte, electricity cooperatives and agricultural production cooperatives.

Cooperatives in the service of the individual and the common good

In addition to agricultural cooperatives, the image in the urban regions of the 19th and 20th centuries was especially shaped by cooperative factory buildings, consumer and bulk purchase companies as well as housing cooperatives. Throughout their history, the cooperatives have always had to cope with difficult times. Particularly affected were agricultural enterprises in connection with political changes. “Once in 1933 the cooperative associations and together with them the cooperatives were brought into line,” says Enrico Hochmuth, “restructuring measures occured after 1945. While production cooperatives played only a minor role in the western occupation zones and the FRG, they played a major role in the Soviet occupation zone and later in the GDR. In 1946, the Soviet Military Administration permitted the establishing of these associations, with order number 160, and a model statute became mandatory. Economic supervision was the responsibility of the newly structured Chambers of Crafts. The Act on the Promotion of Crafts adopted in 1950 or the Ordinance on the Production Associations of Crafts (PHG) of 1958 pushed forward the restriction of crafts and small businesses and the forced collectivisation of cooperatives. The role of the Purchase and supply cooperatives (ELG) of the crafts, was also regulated. Cooperatives, like state enterprises, now had to fulfil requirements within the framework of state planning. After 1990, the companies were again transformed into classical cooperatives or other forms of enterprise.” (p. 6f.) In 2002, the cooperative association in Saxony had 92 productive cooperatives and 235 agricultural cooperatives among its members. Due to their success, they have become more evident in united Germany” (p. 37).

Paying more attention to basic principles of a cooperative way of life and ethics

The historical explanations make it clear that the current problematic restructuring and “modernisation” within the framework of globalisation and centralisation as well as the worldwide radical market neoliberalism endanger the original cooperative idea. Especially in the Swiss Confederation, there are alarming developments, also in the Raiffeisen cooperative banks. It is necessary for cooperative members to demand and live their rights and duties as well as the original concerns and ethics of democratic co-determination of the members in accordance with the cooperative principle. The book presented here makes a valuable contribution to this – as well as to the understanding of the cooperative architecture of modernity. •