“We should learn again to see with the heart”

Thoughts on the 130th birthday of Swiss children’s and youth book author Olga Meyer

by Dr phil. Eliane Perret

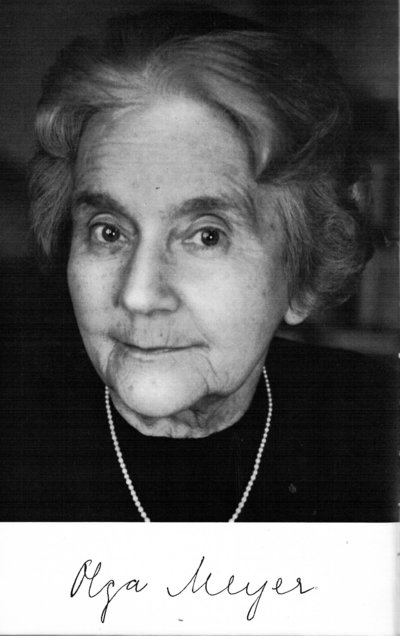

There are books that you never forget, and authors whose works are read again and again by generations of readers. This is why Olga Meyer, the Swiss author of books for children and young people, is one of the most important authors in our country. 30 April 2019 was her 130th birthday.

“Extremely valuable with regard to cultural history”

Olga Meyer’s books, tracing life stories of children from Tösstal, a rural valley in the canton of Zurich, the city of Zurich and other regions of Switzerland, are read by many children and young people who grew up in the second half of the last century, as well as by adults.

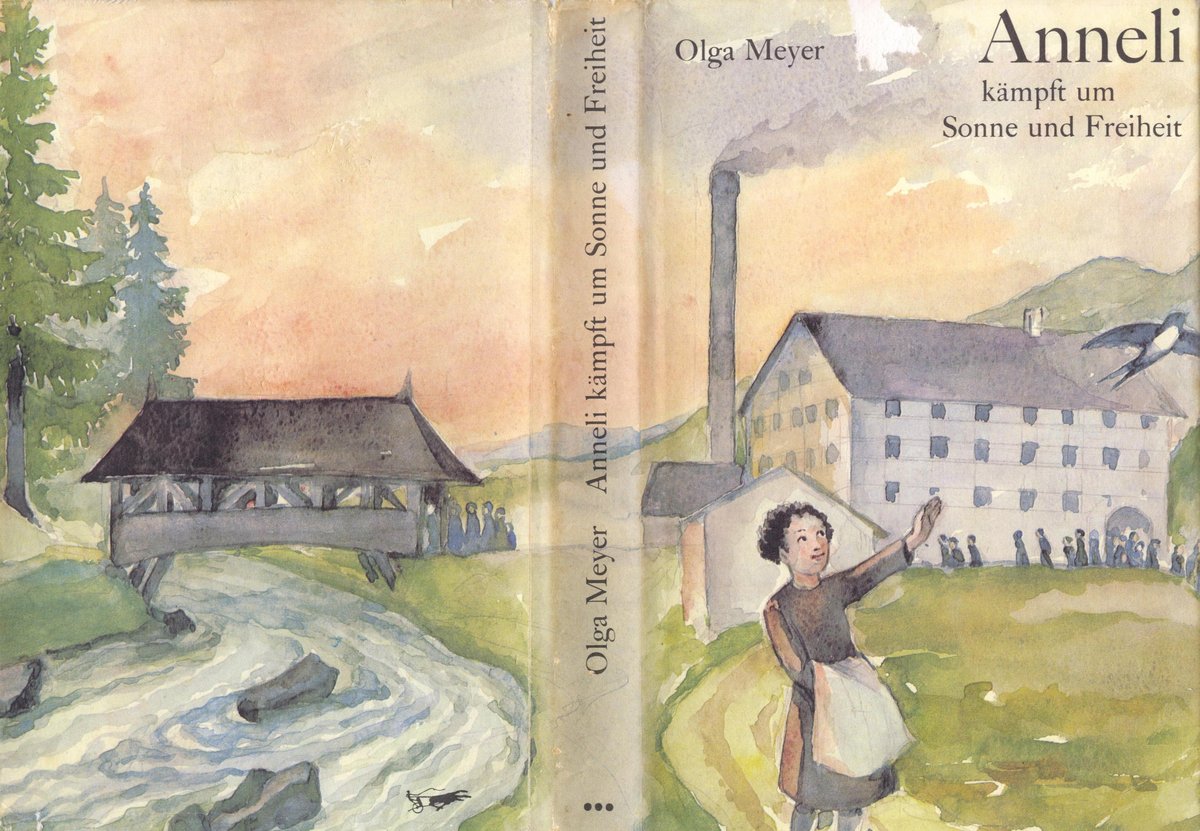

Her “Anneli” trilogy, which takes place in Tösstal, then dominated by the textile industry, has come to be particularly well known. Like other Swiss authors of youth books at the time, Olga Meyer was a teacher, and her books developed from her everyday professional life. Story telling was an important element of her educational work. With her linguistic dexterity, she captivated and still captivates her readers, letting them share, live and empathise with the fate of other children thus giving them an insight into the circumstances of life at the time. “Valuable with regard to cultural history as well as to history” was therefore the conclusion of the book review of her second volume of the Anneli trilogy. As an author, she has fulfilled an important task in the formation of the young generation’s emotional minds, a task unfortunately often missed among today’s authors of youth books. To this day, Olga Meyer’s books are still worth reading. Children may need some support by “big children”, to introduce them to the world of that time and perhaps to the more demanding language than it is usual now. “At that time, we lived on the Zeltweg for a long time, then on the outskirts of the city of Zurich.”1 With this sentence, Olga Meyer begins her memories of her life; in the following, she will often have the say. But let’s begin from the start.

“In every book we write, there always lives a part of ourselves.”

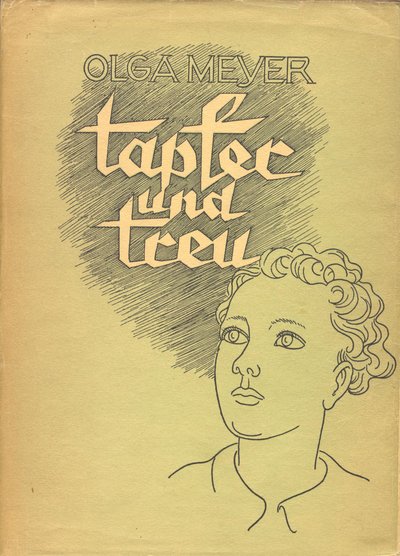

Olga Meyer-Blumenfeld was born on 30 April 1889, and grew up together with her two younger siblings in Zurich on the Zeltweg, which today is in the middle of the city. Her father was a postman, her mother took care of the household as it was usual at that time. Her childhood inspired Olga Meyer to write her books. Be it the life of “Anneli”, to whom she dedicated three volumes and which is based on the life story of her mother, or “Tapfer und treu” (“Brave and Faithful”), which has its roots in her father’s biography. When she died on 19 January 1972, she left behind a great work. If you read her autobiography, you repeatedly find references from her life in her books. “In every book we write there always is a part of ourselves”, she wrote. Often, these are stories of children whose lives were marked by poverty, child labour, heavy blows of fate and personal difficulties on their way through life, always embedded in the economic situation of that time.

“It was a rich seed …”

Thus, her childhood became a stock for her books. For example, music and storytelling. “It was a rich seed that was planted into our children’s souls through the narrating of our mother, and how much did it bond us with this mother. […]” She must have been a brilliant storyteller, because time and again, we fell under the spell of the small episodes she told us about. We never had enough.” The family often played music, the mother on the guitar and the father on the harmonica. “It shook the deepest depths of my inner being and opened up all its doors. I have sung these songs in dim light, I have absorbed them in all their melancholy, longing and joyfulness.” What Olga Meyer experienced there was formative, and she carried it into her life and into her classroom.

“You might as well go home at once...”

Olga Meyer became a teacher. Her parents shouldered a lot to make this education possible for their daughter. First, she took over a school of eighth-graders with 84 children in Windlach for a few weeks. She quickly gained access to the children and realised the importance of the relationship between herself and the pupils for the learning process: “I had found the way to their hearts and now I knew that everything had to go along this path, if it was to be effective on the human being and remain with him or her. A special challenge was her first permanent position in a commune at Lake Zurich, where the Department of Education had sent her. Already the interview with the school president was a challenge: “‘I have been sent by the Department of Education, I am here as ‘Verweserin’2, at the school Rotweg!’ ‘I know – I know!’ the man grumbled between coughing and laughing. ‘You – a Verweserin – with this bunch of eighth-graders! You might as well go home at once. Besides, we don’t need a skirt in the village!’ With this, the man turned back towards his desk on his chair. I was fired.” Olga Meyer did not let herself become discouraged and started her work with these young people. It was demanding. “Whatever I did arose from the empathy with the child’s nature, right from the beginning, the understanding of its needs. Love for him or her, showed me the way.” To the astonishment of the school president, she found access to the adolescents not by rigour and authoritarian measures, but by storytelling and reading to them.3

“Writing a book? That thought never crossed my mind.”

She told her mother’s stories from her childhood in Tösstal to her pupils. Afterwards Olga Meyer wrote them down for herself. This became the basis for the first volume of her Anneli-trilogy. She had never been to the Tösstal herself. “To hear that seems implausible. However, haven’t I known it for a long time? Haven’t I been at home in this Tösstal since my childhood?” She attached great importance to finding the right words: “I wanted to write in a language that was as simple as the content and yet had its beauties – a language that sounded in the child’s ears, a language to learn from.” Olga Meyer carefully and sensitively painted “pictures” with her words for the readers, so that they could individually enhance them with their inner eye. This makes reading her books a delight, even today. The fact that the stories in the schoolroom turned into a book was rather coincidental. “The idea of writing a book about ‘Anneli’ never crossed my mind”. A teacher colleague saw the sheets of paper on her desk by chance and took them. Thus, it happened that in 1918, at the end of World War I, the Association of School Librarians of the City of Zurich published the first Anneli-book entitled “Anneli. Erlebnisse eines Landmädchens” (“Anneli. Experiences of a Country Girl”), in order to be used as a reading series for classes. “It would have never crossed my mind and even less would I have had the courage to go to a publisher with it, all the more since paper was at least as rare as sugar at that time.”

“There is an inner knowledge that cannot be put off by anything.”

The book quickly found its way into schools. It also spread quickly in Germany. After the war years, the aim was to give children and young people an optimistic perspective, also in youth literature. The Spanish flu was still raging. Olga Meyer had also fallen sick when she held the first copy of Anneli in her hands. “I thought: If you have to go, this ‘Anneli’ will remain and give joy to the children. This conclusion gave me consolation in my miserable condition.”

However, not everyone enjoyed this kind of youth literature. Otto von Greyerz, a well-known German language philologist, pedagogue and vernacular writer from Berne, denied the author any knowledge and skills necessary, to write a youth book. Even though he later changed his mind and apologised, this harsh judgement was devastating for the young author. However, she still stood by herself and her ideas: “There is an inner knowledge that cannot be put off by anything. Despite everything, I knew that I had followed a good path. And yet, I decided never to write a book again, except for my pupils and myself – for us to enjoy.” Fortunately, her teacher colleague encouraged her to continue writing. However, as she herself wrote, her heart was not in it anymore. “I had become unfaithful to myself.” She burned that manuscript.

Hansli Mock ignited the spark

As a teacher, Olga Meyer met many children, whose fate touched her. One of them was Hansli Mock, who grew up in very poor circumstances in the city of Zurich. She began writing again. “I wrote from an inner urge, because I could not help myself. [...] I wrote out of joy, solely for the purpose of grasping the heart of that child, drawing from his world and helping him back on the right track. This too, was not an intention, it happened of its own accord, like the words I had to speak to the child, so that they would not get in the way when grasping the content.” Over the years, she has written a great number of books thus reaching a large readership. “I had got in touch with the youth at home and abroad, but also with adults. One has no idea how many adults read youth books, how many elderly people draw from such contents.” She succeeded in doing what one would like to expect from good children’s and youth books. Olga Meyer wrote them with great empathy; she wanted to address her young readers in a natural way in their emotions and give them the opportunity for identification: “Children sense whether a book has been ‘made’ or whether it is inwardly truthful, whether it is genuine. They sense the warmth meeting their needs, the love with which the figures are comprehended. Children live with these figures in such a strong fashion as we adults can hardly empathise anymore. They take sides as if what has happened is something that concerns themselves, and – I have never experienced it differently – they fight with the bearer of the good against the evil that must be defeated. This is what the child wants. That is what it wants to believe in. Even today. It needs that.” In view of the increasingly technical world, she wanted to support children and young people with her books, to develop their personality and to grow up to become fellow human beings who feel and act responsibly. “The world with its highly developed technology in which the child is placed today can arouse its interest, but never warm its heart, give it the sense of security it needs for its inner development.”

“What happened to Anneli later on?”

For the first time, on the occasion of a reading from the Anneli book, Olga Meyer travelled together with her mother to Turbenthal in the Tösstal, where her mother had been born. The world she had described in her stories was now before her, “as if I had come home”. It was a world marked by industrialisation, which had shaped the history of the Tösstal with its weaving mills and spinning mills, closely tied to great poverty, diseases and child labour. Now the mother sat next to the now old factory owner, who had intervened in “Anneli´s” fate in a well-meaning way. “He bid my ‘Anneli mother’ farewell, as if he no longer recognised the poor and the rich, but only the value of a human being.” “Please continue writing! What happened to Anneli later on?”, she had often been asked. This experience made her decide to continue writing Anneli’s story. “What was to become of ‘Anneli’, who had had to enter the spinning mill after only six years of schooling and later on learned a little sewing and cooking from Mrs Bühler in the city? Not much more. She who carried such a great desire in her heart to learn, to know, to do something at a time when the girls were still restricted, when you could not learn what you wished.» Olga Meyer opened-up the perspective in the two following volumes of the Anneli Trilogy.

“I began to delve among history books and chronicles.”

Olga Meyer was a gifted teacher, who supported ‘her children’ with everything she had at her disposal. Her skilfulness in didactic, pedagogical and psychological matters is still impressive today. Writing and music became her compensation along teaching. When she met her life companion, she left her parental home and set-up her own household. She attended lectures on literature at the University of Zurich. “Suddenly I felt a desire to catch up, to deepen what I had been taught and had only half understood in my immaturity.” In later years, she became increasingly interested in history and culture. The reason for this was her book “Tapfer und treu” (“Brave and Faithful”), in which she traced the life story of her father and thus a part of life in the city of Zurich of that time. “I began to delve among history books and chronicles. My interest grew with each passing day, but life around us frightened me. War was spoken of again after the Nobel laureate Bertha von Suttner and her book “Lay Down Your Arms” had been acclaimed and other vigilantes also tried to open the eyes of the world now.”

“If I had only been able to create this one work in my life …”

For Olga Meyer writing was an inner obligation in the face of the youth. “Young people are searchers. They search the world and their own way in this world, also in the book.” She received a lot of echo from readers who had recognised themselves in her stories. One day Olga Meyer met a girl who had spent a year in a household in French-speaking Switzerland learning the language and who suffered greatly from homesickness. A book by Olga Meyer had been a great help to her during this time. “And if I had only been able to create this one work in my life, and what it could give to this girl, I would have had enough proof that books are a guideline in the lives of young people – in good and evil – that they have an obligation and that the author is aware of this, I would like to say that he or she takes an interest in the healthy emotional development of a young person, so, that he or she must love them.” These ethics we desire of all authors of children’s and youth books today. •

1 Meyer, Olga. Olga Meyer erzählt aus ihrem Leben. (Olga Meyer tells about her life.) Rascher-Verlag Zurich-Stuttgart. All the following quotations are from this autobiography and are not referred to any further. May they encourage readers to read the antiquarian book themselves.

2 In the Canton of Zurich, for example, teachers were then called ‚Verweser/Verweserin‘ to take on a position for one year before they were permanently awarded the position in a popular election.

3 She read Rudyard Kipling’s “Jungle Book” to the young people. Depending on current educational needs, she supplemented the text with her own reflections.