What one man can do

“Beat Richner – Paediatrician – Rebel – Visionary” On the newly published book by Peter Rothenbühler about the life of Dr Beat Richner and his life’s work in Cambodia

Book Review

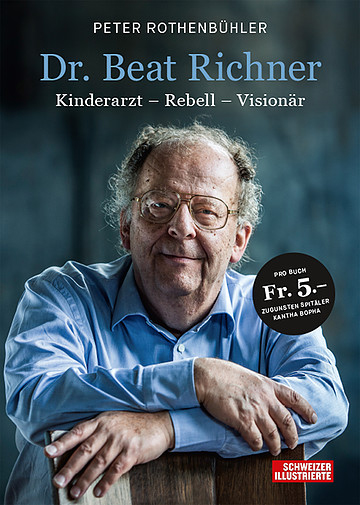

ep. From the cover of the newly published biography a confident Beat Richner is looking at us. Demanding direct human attention, as we know him. Peter Rothenbühler, long-time friend and supporter of Beat Richner, has set out to trace the life of the great Swiss, and he has succeeded excellently. The beautifully designed book, enriched with many photos, is recommended for everyone to read.

“Beat Richner’s life’s work lives on”

Following the foreword by artist colleague Franz Hohler, René Schwarzenbach, President of the Kantha Bopha Children’s Hospital Foundation, takes the floor and gives, under the title “Beat Richner’s life’s work lives on”, a brief overview of the many years of buildup work which his collaborators are now continuing in his spirit. We can only agree with him when he says: “May Beat Richner find as many imitators as possible”. Beat Richner himself wrote this story down in a small white booklet and illustrated it with drawings. It is the fairy tale of a king and his daughter, Princess Kantha Bopha.

“…children who can now build the new Cambodia”

The actual notes begin with Beat Richner’s departure from Cambodia back to Switzerland in February 2017. It is his last flight. For some time he had become a different one, and now the underlying health problems were to be clarified in Zurich. The reader then learns, in an unobtrusive way, about the medical causes of his illness and his stay in a nursing home near Zurich until his death on 9 September 2018. Some of his remains, such as his typical red ties, are lovingly mentioned, before dwelling on his most important legacy: “Five hospitals, an education centre, a maternity hospital and several million healed children who can now build the new Cambodia”.

“…without running the risk to get lost in empty talk”

The second, most comprehensive chapter is devoted to the history of his life’s work, beginning with his childhood and the years of study of the great physician.

We learn a great deal about his childhood as the fourth child of a family of teachers on the Zürichberg and about his school days, when he stood out less through diligence than through original ideas and his quick-wittedness. The anecdotes interspersed make us smile; we feel his growing generosity and suspect that Beat Richner early on knew how to establish himself with independent ideas.

Music took an important place early in his life. After graduating from high school, the career of becoming a professional cellist was open to him, and soon he appeared under the stage name Beatocello with a full-length programme in small theatres.

«I am the doctor PC 80-60699-1

Do you remember this very number,

We still need money, just your money

Why poor children should not have

the right of getting drugs and care

Why we wonder

We don’t surrender

Thank you, thanks a lot.»

Song with which Beatocello circumvented the ban on openly advertising for donations.

Enable the people of the third world to live in dignity

Then he decided to study [medicine] after all. “As a doctor, I thought, manyserious questions, injustices and hardships could be approached most meaningfully without running the risk of getting lost in empty talk.” Soon he wanted to launch a medical aid project, but failed due to the lack of financial support from the federal government. But the idea did not let him go. Anticipating his own way of life, he said that the best defence of the country was “to meet the people of the Third World and to enable them a life in dignity in their own world”.

Before Beat Richner and a colleague opened their own paediatric practice at the Römerhof in Zurich, he volunteered for Red Cross aid missions, first in Tanzania and then for the first time in Cambodia in 1974, where he remained until the overthrow by the Khmer Rouge in 1975. In addition to his work as a paediatrician, he became an important figure as an artist in the small theatre scene.

“Il y a des enfants qui meurent,

leurs mères qui pleurent,

les fonctionnaires qui traînent,

les bureaucrates qui traînent.

Leurs train tues des vies.

C’est pourquoi

il y a des enfants qui meurent,

des mères qui pleurent,

des fonctionnaires qui traînent …”

Song by Beatocello, with which he denounced the “poor world medicine” of the WHO

“Do something sensible with your journal”

Richner’s success story began in 1991. He wanted to return to Cambodia and rebuild the Kantha Bopha Children’s Hospital, which he had had to leave head over heels fifteen years ago. Peter Rothenbühler accompanied him from the very beginning as editor-in-chief of Schweizer Illustrierte. At first it was all about finding the necessary finances. “Do something sensible with your journal,” said his wife. He published an appeal for donations that raised the first 60,000 dollars. Beat Richner could start.

Quality medicine for everyone

It was Richner’s credo that medicine should not differentiate between poor and rich people. He did not shy away from taking on the World Health Organisation (WHO) for this reason, which represented a different health strategy.

Accordingly, it was clear to him that his hospitals had to be equipped with the latest equipment so that the appropriate examination methods could be applied. He was aware that medical work was essentially determined by the selection of personnel. That’s why he took the selection of his employees into his own hands. In contrast to state institutions, they received an appropriate salary, with which he successfully countered the corruption that was widespread in Cambodia at the time. The patients were treated free of charge, which made it possible for all patients to have access to good professional treatment. “With his approach Richner contradicted the international medical authority WHO so diametrically that there had to be a massive headwind.” But not only at the WHO, also in Switzerland Richner bit on granite for quite some time with his request. The campaign against him lasted more than 20 years and took him a lot of strength.

What he achieved in the following years is unbelievable

Despite all the stones that were put in his way, Beat Richner remained true to himself and worked tirelessly. His hospital was overrun by patients, and soon a second hospital was needed, for which the king provided part of his land. Rothenbühler carefully describes how new projects were planned and implemented in the following years. Five hospitals, a congress centre and a maternity hospital were created.

The best model ever seen for medical aid in poor countries

The daily struggle for the vision of equal medicine for all was gruelling. Raising the necessary money became one of Beat Richner’s biggest fields of responsibility in the following years. Several times a year he travelled to Switzerland with his cello to collect the necessary financial basis for his projects with his performances. That Beat Richner did not always behave diplomatically and did not mince his words is not to be blamed on him – on the contrary! At the beginning of the new millennium there was finally a turnaround in the international assessment of his projects. The federal government currently supports the Kantha Bopha Foundation with four million Swiss francs per year. Since 1994, more than 60 million francs have thus flowed into the hospitals. The Cambodian government, for its part, doubled its contribution in 2016 to six million dollars annually.

“I am the Beatocello and would like to have it comfortable now”

When Beat Richner died in 2018, his life’s work was on a firm footing and his succession was settled. In his era, 15.4 million children were treated as outpatients and 1.7 million seriously ill children as inpatients. 80% would have had no chance of survival without Kantha Bopha. 85% of all sick children in Cambodia are treated there. A total of 2400 beds are available and 2500 Cambodian employees work there. The financial basis is more solid, even though the hospital is still urgently dependent on donations. Beat Richner could have had it comfortable now, as he had always wished: “I am the Beatocello and would like to have it comfortable now.” (I bi der Beatocello und möchts jetz gmüetli ha.) Unfortunately, it was not granted to him. •