Alfred Escher and the democracy movement – Paving the way for modern Switzerland

Alfred Escher and the democracy movement – Paving the way for modern Switzerland

by Dr rer. publ. Werner Wüthrich

Every year provides an opportunity to recall historical events that have had a significant impact on the economy and politics. This is also the case in 2019: two hundred years ago – on 20 February 1819 – Alfred Escher, for example, was born. Today, his statue stands prominently on a four-metre-high granite pedestal in front of Zurich Main Station. Escher was an influential politician in the Canton of Zurich and in the Confederation, an economic leader and a railway entrepreneur.

One hundred and fifty years ago – on 18 April 1869 – the voters of the Canton of Zurich voted in favour of a new constitution that contained numerous popular rights and was truly revolutionary. The following lines are dedicated to both events.

Alfred Escher (1819–1882)1 came from an old, influential family of councillors and guilds in the city of Zurich. He was 36 years in the Cantonal Council, 34 years in the National Council, seven years Government Councillor, founder and head of the Nordostbahn (the first major railway company in Switzerland), founder and chairman of the board of Schweizerische Kreditanstalt (now Credit Suisse, CS), Founder and supervisory board member of the Schweizerische Rentenanstalt cooperative (now Swiss Life), president of the management and board of directors of the Gotthardbahn-Gesellschaft, responsible as a member of the government for education, co-founder of the Swiss Federal Institut of Polytechnic (now ETH) and lifelong member of the school board and many other things – most of them at the same time. Escher was probably the most important and influential economic leader and politician in the history of the federal state.

As a liberal politician, he defended representative democracy and dominated politics like few other politicians before and after him. He became the main opponent of the opposing Zurich democracy movement, which demanded co-determination and popular rights and fought against the “Escher system”.

Alfred Escher as economic leader and liberal politician

Alfred Escher belonged to the liberal party that determined politics in the years before and after the founding of the federal state in 1848.2 He was disturbed by the fact that railway construction had hardly begun in Switzerland at that time. Great Britain already had a rail network of 10,000 kilometres. Germany and France were also far ahead. The industrial revolution was in full swing, and new means of transport were essential to transport raw materials such as cotton, grain, iron and energy sources such as coal quickly and to deliver the finished products back to more distant markets. This was particularly important for Switzerland because it had neither raw materials nor large markets where it could sell its industrial products. Tourism was also still in its infancy. The few tourists still travelled through Switzerland and its mountains in horse-drawn carriages. This backwardness had to be made up as quickly as possible – that was Alfred Escher’s central concern.

Only – who should take over the direction? In 1848 and in the years that followed, the Confederation only had a budget of a few million francs and first had to set up its own administration. The railways only had an office in the Post and Building Department. It was therefore only natural for Escher that private companies, in collaboration with the cantons and communes, should take over the construction of the railway facilities. The cantons were to grant the licences, which the Confederation approved as the coordination office and supervisory body. The latter, however, reserved the right to buy back the railways at a later date. Escher succeeded in convincing most of the National and Cantonal Councillors of this concept, so that they gave the go-ahead.

From the very beginning, Escher had everything in mind that was needed to set up the railway system. In 1853 he founded the Nordostbahn. The Cantons of Zurich and Thurgau and the cities of Zurich and Winterthur each contributed CHF 4 million, private shareholders CHF 6 million and foreign investors CHF 5 million. Just a few weeks later, construction crews began laying the rails from Zurich to Lake Constance. Ten other railway companies were established in other cantons.

Escher realised that the topography of Switzerland required a relatively large number of tunnels and bridges. But the engineers were missing. In 1854 he was significantly involved in the foundation of the Swiss Federal Institute of Polytechnic in Zurich (today ETH) and was also elected to the school council. He invited professors from abroad, so that soon a first group of engineers could be trained. In 1855 already 71 students followed the lessons, in 1860 there were 336.

Because the public funds of the cantons and communes were far from sufficient and Escher and the railway companies did not want to become dependent on foreign banks, Escher founded the Schweizerische Kreditanstalt in 1856, which specialised in the issue of securities (shares and bonds). (The savings banks’ funds were not suitable for this high-risk business.)

Escher as a politician

Alfred Escher held many political posts alongside the chairmanship of the Nordostbahn and the Schweizerische Kreditanstalt. He spent many years in the city parliament and in the parliament of the Canton of Zurich. As a member of the Government Council, he was responsible for the education system and established a number of reforms. For 34 years he was a member of the National Council and acted as President for several periods. He succeeded with mastery in building up networks that supported him, both in cantonal and federal politics, so that he could quickly push his plans through and implement them. Everything he took in hand succeeded – and, above all, a quickly. Within 10 years he made up leeway in railway construction between Switzerland and the rest of the world, and Zurich became the centre of Switzerland in terms of transport infrastructure and economy during Escher’s time. Escher personified pioneering spirit, free enterprise and economic awakening like hardly anyone else. Many of today’s large companies were founded during these years. In the years before 1848, Zurich had been much smaller than Basel, Bern or Geneva. That was supposed to change fairly soon.

Alfred Escher was part of the liberal-representative regime of his time. However, one cannot do him justice if one calls him a grabby capitalist or a “railway baron” who has only the stock market price and his profit in mind. Escher was popular, was repeatedly elected to political posts, sang in the church choir of his church in Wollishofen, and the poet Gott-fried Keller was a regular guest at Escher’s. He undoubtedly had shares in “his” Nordostbahn and “his” Kreditanstalt, but by no means so many that he could have determined as a sole shareholder. In addition, he was rich by birth, and he would not have had to burden himself with the many almost superhuman tasks and public duties. It is well known that he waived his salary as president of the Nordostbahn in difficult years. Nor did he intervene when his Nordostbahn was placing its tracks through the middle of his private garden (today’s Belvoir).

Emergence of an opposing democracy movement

Although Escher was repeatedly elected to his many posts, a strong opposition grew against the “Prinzipate Escher”, against the almost princely power Escher ruled the Canton of Zurich and was able to do almost everything he wanted thanks to his many contacts. This didn’t fit into Switzerland’s cooperative understanding of the state. Politically, Escher was a typical representative of the liberal-representative regime. In the canton and in the Confederation, he firmly expressed the opinion that regular referendums slowed down political processes, hindered progress and were voted on by the ordinary people without sufficient expertise. And he stuck to this opinion for the rest of his life.

At that time, the cantonal parliament and government were almost exclusively composed of representatives of the Liberal Party, which had dominated the representative democracy in the canton since 1831. The democracy movement, as the opponents called themselves, came from almost all classes of the population: Craftsmen, farmers, teachers, professors, editors, entrepreneurs and working man. They all felt that the principle of popular sovereignty had stunted in the Escher system. The more dominant Escher’s influence became, the more the opposition increased. Traditional tensions between the city of Zurich as the centre and the rural regions also emerged.

The various opponents suffered from all sorts of hardships and rightly felt that the government was busy with “major topics” and did not support sufficiently their concerns. It was also disturbing that the population had no say in the choice of routes for the railways. It was decisive for the population and their economic situation throughout Switzerland whether their commune received a railway station or not – or may be later. Conflicts were inevitable.

The Winterthur local newspaper “Landbote” as the centre of the democracy movement

The intellectual centre of the democracy movement was the newspaper editorial office of the “Landbote” in Winterthur with its editor Salomon Bleuler – the École de Wintertour, as it was named in French-speaking Switzerland.2 Bleuler often fenced with the journalists of the “Neue Zürcher Zeitung”, which was affiliated with the liberal government. The city of Winterthur itself belonged to the “rural area” and was often in opposition to the borough of Zurich. Karl Bürkli, an early socialist and president of the Konsumverein (coop), was the spokesman of the movement there.3 Workers also participated, but were clearly in the minority. For a long time one could not speak of a democratic party, as there were no structures at all.

In 1865 the Cantonal Parliament laid the constitutional groundwork for a political transformation of the greatest scale, which could almost be described as a revolution.4 The Canton of Zurich was lagging behind other cantons and the Confederation in terms of popular rights. The liberal constitutional state with individual freedom rights, separation of powers and representative democracy had hardly changed since 1831. The Federal Constitution of 1848, on the other hand, already provided that 50,000 citizens could request by signing a referendum on the question of whether the constitution should be renewed in general. In 1865, the cantonal parliament of Zurich introduced this possibility in the Canton of Zurich, and the people agreed to the new article of the constitution. 10,000 signatures were sufficient to demand a total revision of the constitution. If the people agreed, a further ballot would be held to elect a 222-member constitutional council with the task of drawing up a new constitution. A demanding procedure, not only at that time!

Via the democratic revolution towards pure democracy

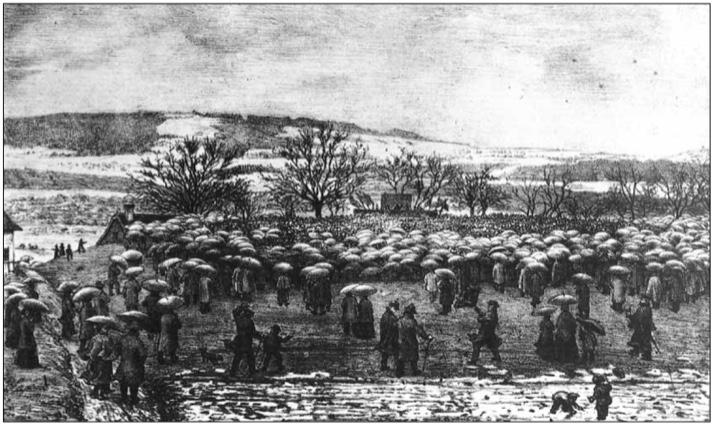

In 1867 there came movement into the politics. A committee of 15 distinguished men from all over the canton was formed. On 15 December 1867, they called for four large popular assemblies (Landsgemeinden) – to Zurich, Uster, Winterthur and Bülach. Despite rain and snow, about 20,000 citizens gathered and demanded a total revision of the constitution. Three times as many as the ten thousand signatures requested were quickly collected, and a ballot was held on 23 January 1868. The polling was a high 90 per cent. The people voted clearly with over 80 per cent in favour of the total revision of the constitution and also voted yes to the election of a constitutional council. The message was clear, Salomon Bleuler wrote in large letters in the Landbote: “We want a political regeneration of the canton!”

Now things were moving fast. As early as March 1868, the 222-member Constitutional Council was elected – above all people from the democratic movement. They immediately started to draft a new constitution. A consultation was held throughout the canton, so that everyone could express his or her wishes and concerns. “Referendum and initiative,” wrote the Landbote in May 1868, “form the two pivotal points of the political-democratic movement and the decisive demands of the people.”5

The work of the Constitutional Council was public. Thus the speakers not only spoke to their colleagues in the Council, but also to the public, and the newspapers published minutes and commentaries.

What was new – as Bleuler wrote in the Landbote – was the idea of establishing a pure popular rule in a large, economically well-developed canton. Landsgemeinden had long existed in smaller cantons, and they had proven to be effective. While there the votes and elections took place in one public place (for example on the Landsgemeindeplatz in Glarus) and were voted on publicly, in the large Canton of Zurich this was supposed to take place decentral and secretly in the numerous communes. With the new communication tool of telegraphy, the individual results could quickly be communicated to form an overall result. Such was the plan.

Constitution of the Canton of Zurich of 1869

The Constitution contained the following key points:6

People’s sovereignty and people’s rights

a) While the Constitution of 1831 had still stipulated that the power of the state would be exercised by the cantonal parliament as the representative of the people, Article 1 of the new Constitution read as follows:

“The power of the state is based on the entirety of the people. It is exercised directly by the active citizens and indirectly by the authorities and officials”. (Article 1)

b) The people, i.e. the majority of the voting citizens, elect the cantonal government directly (Art. 37). At the level of the districts, the civil servants and the governors are also elected directly by the people (Art. 44) – also the judges. At the communal level, even the clergy and teachers of the elementary school are elected by “community members” and confirmed after six years (Art. 64).

c) The Parliament subordinates to the referendum “all constitutional amendments, laws and concordats” as well as factual votes and financial decisions which exceed CHF 250,000 or CHF 20,000 in the case of annually recurring expenses (Art. 30, 31, 40).

d) Collecting 5,000 signatures, the people have the right of initiative both in constitutional matters and for laws. It can therefore initiate the legislative process and also vote on the final result in an obligatory manner. It therefore had the first word, if it so wanted, and in any case the last (Art. 29).

Social policy

The Constitutional Council had also done pioneering work in the socio-political field and provided for impressive innovations:

a) Progressive taxation is introduced (Art. 19).

b) A state bank, the Zürcher Kantonalbank, should take greater account of the needs of farmers and craftsmen (Art. 24).

c) Elementary education becomes compulsory and free of charge (Art. 62).

d) The canton shall promote cooperatives as based capacity building and enact laws for the protection of workers (Art. 23).

e) The coalition ban is abolished – a prerequisite for the formation of trade unions. (Art. 3)

Municipal liberties

The new principles should also be fully applied at communal level. This was stated in Article 51:

“In particular, the communal assemblies are responsible for: supervising the departments of the communal administration assigned to them, determining the annual estimates, approving the annual accounts, approving taxes, approving expenditure exceeding an amount to be determined by them, and electing their respective heads [...].

At the time, this constitution was a truly revolutionary reform. It did not consist of a number of individual demands, but was an overall concept that confirmed liberal achievements such as equality of rights, individual freedoms and separation of powers, and supplemented and combined them with far-reaching popular rights and socio-political innovations. This reform also included economic freedom. Article 21 read:

“The exercise of every profession in art and science, trade and industry is free. Reserved are the legal and law-enforcement regulations which are required for the public good”.

Historic Vote on 18 April 1869

65 per cent of the voters agreed to the reform. The result was celebrated with firecrackers and public festivals. Constitutional law expert Alfred Kölz commented: “In a far-reaching regulation Zurich was the first canton to include economic and social matters in its constitutional law.” The newspaper “Landbote” praised the event as the most significant event in the field of newer state institutions. Bleuler wrote in the “Landbote” that the new constitution was

“in a word the first consistent attempt to implement the idea of pure rule of people in a form corresponding to modern cultural conditions and to replace the venerable Landsgemeinde suitable only for small communes by an institution whose cornerstone is the secret ballot within the communities. […] 18 April introduced this principle into state life of the Canton of Zurich, and we welcome this day with the full glow of joyful trust, based on the deep conviction in the beneficial effect of the new people’s rule.”7

The great democratic upheaval in the Canton of Zurich came true because the ground was already prepared. Worth mentioning here are similar democratic movements in other cantons at the same time, the cooperative understanding of the Confederation, the tradition of Landsgemeinde (rural commune) in a number of smaller cantons, which had functioned well for centuries, and furthermore, earlier approaches to direct democracy in various cantons.8

Persistent political high of the Democrats

In May 1869 for the first time the government was elected by the people, and change was likely to occur. The liberals, who in the past decades according to the liberal-representative constitution had almost arbitrarily determined political life as representatives of the people, were deselected and replaced by the democrats. Moreover, the democrats provided the two members of the Council of States. Furthermore, the majority of the Zurich representation in the National Council were Democrats. They obtained an absolute majority in the cantonal elections. The “Landbote” changed from an oppositional regional newspaper into a newspaper that was read with interest throughout the canton and also in other cantons. It was one of the very few revolutions that took place democratically and without a single rifle shot. (Almost at the same time, the people of Paris tried to introduce a new order with people’s rights. The Commune de Paris of 1871 ended in a bloodshed.)

However, it is striking that Alfred Escher and his “system” – although “big losers” of the historic vote of 1869 and in the following elections – was re-elected to the National Council with a brilliant result in the same year (and again and again thereafter). Furthermore, he was to take on new major tasks at federal level with the construction of the Gotthard tunnel. This shows that discontent was not so much about the person of Escher but about the “system”. The people of Zurich wanted to change the structures of the state. At the same time they paid tribute to Alfred Escher and his achievements. The Liberals and Democrats got closer to each other in the following years, they administered the canton jointly and later joined forces to form the Liberal Party (Freisinnig-Demokratische Partei FDP). FDP Switzerland was not founded until 1894. We can also find the Democrats on the left side of the political spectrum: The Social-Democratic Party of Switzerland SPS was founded in 1888.

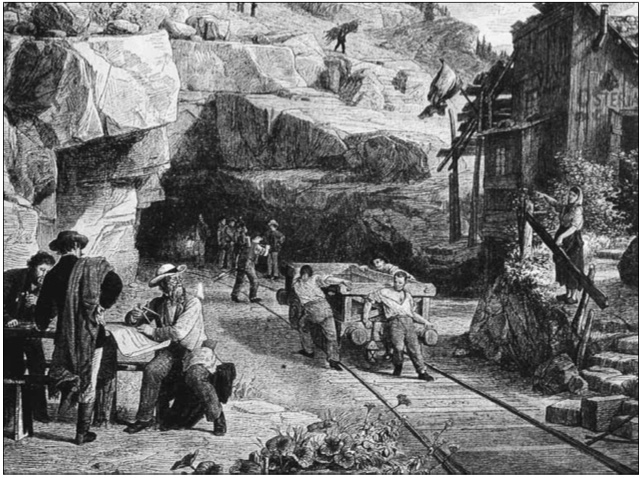

Construction of the Gotthardtunnel

In the 1870s, as president and organiser of the Gotthard Society, Escher took final responsibility for the construction of the Gotthardtunnel. The Gotthard contract he negotiated intended construction costs, calculated at CHF 187 million (at that time’s value), to be partly covered by public subsidies. Italy contributed 45 million, Germany 20 million and Switzerland 20 million. In addition, shares for 34 million and bonds for 68 million were issued by the Gotthard Society and the Kreditanstalt. Escher took a big risk – even the investors (who subscribed for shares or acquired bonds) could not be sure whether they would get their money back – because nobody knew what would be found inside the mountain. These risks were reflected in the stock price of the Schweizerische Kreditanstalt. Stocks rose if the construction teams made good progress. Stocks fell in the event of difficulties like water intrusions, strikes of the workers or after cost overruns of 40 million had become known. However, within eight years the construction work was completed on schedule. The construction workers and the engineers trained at the “Poly” (Swiss Federal Institute of Polytechnic) had done an excellent job. The two construction teams, who worked together for years in the 15-kilometer main tunnel with simple machines and tools, met in the middle of the Gotthard with a deviation of only a few centimetres. However, the safety precautions were still inadequate. There were many accidents with numerous fatalities. In 1882, the central north-south link with 62 tunnels, 34 bridges and 10 viaducts was inaugurated – a major event and a celebration for Switzerland and the whole of Europe. Further bold railway projects were to be realised in the following years by entrepreneurs who emulated Escher – such as the Bernina Railway at 2250 m or the Jungfrau Railway at 3500 m.

Alfred Escher as a political challenge

The person of Alfred Escher embodied pioneering spirit, private initiative and free enterprise, economic awakening and dynamism, good education at school and at work, technological progress and the courage to tread new paths in banking, while the democracy movement advocated power-sharing, the consistent separation of powers and direct participation and responsibility of the people, laws for the protection of workers, social and regional balance and greater involvement of the concerns of all levels of the population. – Both were powerful attitudes of mind in the 19th century. However, the tensions did not end in class struggle – as Marxist historical view had suggested. Rather, the two currents converged on cooperative soil of the Swiss Confederation, complemented each other in political play and prepared the ground for the development of modern Switzerland.

Liberal-democratic Economic Concept of Switzerland

Five years after the adoption of the new Zurich Constitution and after similar revisions in other cantons, the Councillors totally revised the Federal Constitution in 1874. Like the Zurich people, they combined economic freedom with direct democracy and developed a coherent, liberal-democratic economic concept for the whole country, which is unique in the world and still applies today. It is based on three pillars:

- Economic freedom (at that time freedom of trade and commerce), which sees itself as an individual freedom and fundamental right.

- The principle of economic freedom: It requires that the essential regulatory framework must also be free. In concrete terms, this means that deviations from freedom are possible – but only with an obligatory constitutional vote.

- Direct democracy: In addition, the people can largely determine the individual concrete cornerstones of the regulatory framework themselves via the constitutional right of referendum and initiative (since 1891) – for example in a factory law at that time, today in agricultural policy or currently in company taxes – and they can also set the course in economic policy themselves (which has happened several times).

The people said Yes on 19 April 1874. This laid the constitutional foundations for the more than 200 economic and social votes that have since taken place in the Confederation (Linder 2010) – on issues of economic order, the world of work, education in schools and professions, industrial policy, social insurance, taxes and finance, agriculture and the environment, banking and monetary affairs, immigration and also on economic contracts with other countries. Countless votes at cantonal and communal level were added. The concept was repeatedly tested and sometimes questioned in principle – for example by the EU, which wants to involve Switzerland even more politically with a framework agreement, ignoring the fact that its centralist behaviour and policy from above do not fit in well with a free economic concept that is based directly on the people.

An overall judgement is possible after 150 years: Today’s order is not perfect, but it is impressive, and Switzerland is in an excellent position by international standards – so the highly efficient and impressive kind of economic policy that Alfred Escher initiated may be as good as it is, but it really succeeds if the people think along and share responsibility for it – for which the democracy movement paved the way in the 19th century. This will be shown in the following by means of a concrete example:

Railways – private or state-run?

From the very beginning, the “Staatsbähnler” (state railway supporter) in Berne repeatedly demanded that the railways be operated by the state. It was not until 1891, however, that a concrete project was presented, when the private railway companies had almost completed the construction of today’s railway network of around 3,000 kilometres: Federal Councillor Stampfli proposed in a first step to the Federal Councils to nationalise the Schweizerische Centralbahn – the second largest railway company in Switzerland after the Nordostbahn. It covered the Mittelland and led from Basel through the Hauenstein Tunnel via Lucerne to the Gotthard, thus also having a strategic importance in political terms. In addition, the Centralbahn was one of the main shareholders of Alfred Escher‘s Gotthard Society. There were good reasons to merge the networks of the various railway companies and have them operated by the federal government. Parliament agreed and a referendum was held.

On 6.12.1891 the “Staatsbähnler” together with the Parliament and the Federal Council experienced a nasty surprise. The sovereign voted quite differently than they had hoped. More than 60 per cent of voters and most cantons rejected nationalisation. The results in individual cantons were interesting. The electors of the Canton of Zurich voted against with almost 80 per cent, the Canton of Berne supported with 60 per cent. The four Gotthard Cantons of Ticino, Uri, Schwyz, Obwalden and Nidwalden all voted with over 90 per cent against nationalisation. They were obviously not prepared to give up control of the Gotthard, which had played a central role in their lives and history for centuries. The Canton of Valais even voted against with 95 per cent, the Canton of Schaffhausen with 91 per cent. The reasons may have been quite different. Federal Councillor Stampfli was disappointed and resigned. It became apparent that Switzerland was by no means (and still is not) a homogeneous economic area. If Parliament had simply enforced nationalisation, as is customary in a representative democracy, there would certainly have been serious political unrest.

However, the mood changed: just seven years later – on 20 February 1898 – the sovereign agreed with more than 60 per cent to an even more far-reaching bill that would lead to the foundation of the Swiss Federal Railways SBB. The polling was over 80 per cent, in the Canton of Zurich even 89 per cent, which shows the importance of the proposition.9 Four of the largest private railway companies – the Centralbahn, the Nordostbahn, the Vereinigte Schweizerbahnen and the Jura-Simplon-Bahn and a little later also the Gotthardbahn – were to be sold to the federal government for around CHF 1.2 billion. Contributed to the clear people’s Yes had a highly unpopular strike. The employees of the Nordostbahn, which at that time covered almost 40 per cent of the Swiss rail network, went on strike for three days (from 11 to 13 March 1897) and paralysed almost all rail traffic nationwide. All wheels stood still, and the familiar noise in the stations fell silent. (Today strikes are forbidden in rail traffic.)

The mood had changed significantly in just a few years. After the second vote, a large part of the rail network previously built by private companies was sold to the federal government. The Gotthard cantons were still against it – like the Canton of Valais and other cantons in French-speaking Switzerland. But the decision was accepted and the way was clear for the foundation of SBB in 1902. Today, there are still three types of railways: private railways as public limited companies in which private individuals, communes and cantons participate, cantonal urban railways (S-Bahn) and the SBB. Today they are all interconnected in a timetable and tariff association. – The railway system enjoys a high reputation throughout Switzerland, and the Zurich region now has the densest railway network in the world – not least thanks to the man whose statue stands in front of Zurich Central Station. •

1 Jung, Joseph. Alfred Escher 1819–1882, Aufstieg, Macht, Tragik. Zürich 2007, p. 162–287

2 Guggenbühl, Gottfried. Der Landbote 1836–1936. Hundert Jahre Politik im Spiegel der Presse. Winterthur 1936, pp. 125

3 Schiedt, Hans-Ulrich. Die Welt neu erfinden, Karl Bürkli (1823–1901) und seine Schriften. Zürich 2002

4 Kölz. Alfred. Neue Schweizerische Verfassungsgeschichte II. Ihre Grundlinien in Bund und Kantonen seit 1848. Berne 2004 – mit Quellenband, pp. 48

5 Guggenbühl loc.cit. p. 196

6 Kölz loc.cit. p. 63–74

7 Guggenbühl loc.cit. p. 203

8 Roca, René. Wenn die Volkssouveränität wirklich eine Wahrheit werden soll … Die schweizerische direkte Demokratie in Theorie und Praxis. Zurich 2012, p. 201–207

9 von Muralt, Leonhard. Zürich im Schweizerbund. Zürich 1951, p. 183

Further literature:

Linder, Wolf; Bolliger, Christian; Rielle, Yvan. Handbuch der eidgenössischen Volksabstimmungen 1848–2007. Berne 2010

[Translate to en:] Die Förderung der Genossenschaften als wichtiges Postulat im Zürcher Verfassungsrat

[] Vor allem der Frühsozialist Karl Bürkli setzte sich vehement für Genossenschaften ein. Das Protokoll von Karl Bürklis Rede zum Genossenschaftsartikel zirkulierte als Flugblatt. Er forderte darin die staatliche Förderung der Genossenschaften und die Einrichtung der Kantonalbank, um den Handwerkern und Bauern und den zahlreich entstehenden Genossenschaften zu günstigen Krediten zu verhelfen.

Die Genossenschaftsbewegung – so hoffte Karl Bürkli – würde sich auf breiter Linie gegen den Kapitalismus durchsetzen. Die Genossenschaften müssten jedoch vom Staat nicht subventioniert, sondern lediglich bei der Beschaffung von Anfangskapital unterstützt werden. Weg und Fernziel war für ihn die allmähliche «Republikanisierung der Industrie durch Arbeitergenossenschaften» bzw. die Bildung von «Produktivassociationen».1 Dafür gewann er allerdings keine Mehrheit – für die staatliche Förderung der Genossenschaften dagegen schon. Mit der direkten Demokratie werde die Klassenherrschaft durch die integrale Volksherrschaft abgelöst – so Bürkli. Das Volk irre sich in Sachabstimmungen weit weniger als in Wahlen.2

Die Förderung der Genossenschaften hat bis heute Tradition: 2012 beschlossen die Stimmbürger der Stadt Zürich mit einer grossen Mehrheit, den genossenschaftlichen Wohnungsbau zu fördern und so den Anteil der Genossenschaftswohnungen an den gesamten Mietwohnungen der Stadt von bereits hohen 24 auf 33 Prozent zu erhöhen. Kurz darauf wurde eine Volksinitiative im Kanton angenommen, die verlangte, dass ein Fonds zur Förderung des gemeinnützigen Wohnungsbaus eingerichtet werde.

1 zit. in Kölz II 2004, S. 78

2 Roca, René (Hsg.), Frühsozialismus und moderne Schweiz. Basel 2018, S. 81 f