Jaap ter Haar – “Boris” (“The Ice Road”)

Jaap ter Haar – “Boris” (“The Ice Road”)

The miracle of Leningrad in the young adult book

by Dr phil Diana Köhnen

One of the darkest chapters of the National Socialist regime and the Second World War was the siege of Leningrad, now St. Petersburg, by the German Armed Forces from 1941 to 1944. Only a few people in Germany still know about it, probably least of all the young people.

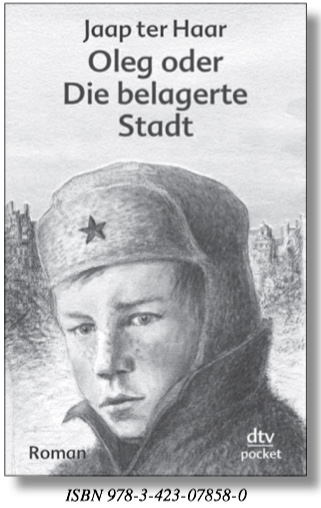

An exciting and moving book for young people about the German siege of Leningrad in World War II was written by Jaap ter Haar. The Dutch author, who himself witnessed the German occupation of Holland, then fled to France and became a member of the French Resistance, wrote mainly children’s and young adult books in his later life. They became world-famous and were translated into many languages. One of them is the book Boris,1 which, from the point of view of the young protagonist Boris and his girlfriend Nadia describes humanly responsiv the drastic situation of the civilian population in the city.

Boris’s father died during one of the food transports by truck across the frozen Ladoga Lake. This lake is the only connection to unoccupied Russia. If it thawed, they still tried to maintain the food supply for the city; the truck sank and Boris’s father died, which struck many who took the risk of crossing the lake. The book begins with Boris’s memories of his father, and one soon learns that Boris’s mother has become ill through the many hardships and suffering. It is Boris who has to pick up the daily small food rations in the soup kitchen for the family. He goes this way together with Nadia, whose father and brother died of hunger. Nadia feels guilty because she picks up four food rations anyway and finally hands them over to Boris for his sick mother. Although it is planned to evacuate all children from the besieged Leningrad, Boris is determined to stand by his mother and not leave the city. One day Nadia and Boris get the idea to buy more food. They know of a potato rental outside the city where they can get potatoes to cook a more nutritious soup for their mothers.

They embark on the arduous journey to no man’s land between enemy lines. There Nadia collapses from weakness and exhaustion. German soldiers appear, and Boris is determined to shoot them with his father’s army pistol, which he always carries with him. Contrary to expectations, the three German soldiers take care of the children and give them their food ration so that both survive. After a long and controversial discussion, the soldiers decide to take the children back to the Russian lines and accompany them there.

From a piece of cloth, a white flag is made, which they carry in front of them to announce to the Russians that they are coming with peaceful intent. The Russian soldiers approach them with great mistrust, but bring along an interpreter who translates the concerns of the Germans. The children are handed over, but one of the Russian soldiers suggests shooting the German soldiers because he suspects that they came to spy on the Russian positions. But something unexpected happens: Boris intervenes and asks them to let the soldiers go, because they came in good intention: “Then Boris looked over to the Russian lieutenant. The grimly harshness on his face had given way to an expression of wonder. The soldier who had wanted to shoot had lowered his gun barrel and scratched his feet in the snow. Other soldiers had casted down their eyes. The sergeant stared at Nadia. It was dead silent again. The lieutenant waved to the interpreter. ‘Tell them they can go, Ivan Petrovich! He hesitated for a moment, as if searching for words. Also tell them that we are grateful to them. It would be bad if all humanity were lost in this war.’” (all quotes translated by Current Concerns)

The German soldiers say goodbye, not without leaving a piece of bread and sausage for Boris and Nadia. “Once again Boris felt the familiar pressure of the big hand on his shoulder. Then the commander rose. Slowly he looked around in a circle, with the same troubled smile that Boris had seen on his face before, he beat his heels together and greeted – tight and upright, as the German soldiers are used to. And finally something good happened on this long, miserable day. The young lieutenant of the Red Army adopted an attitude. ‘Department stand still,’ he shouted. All the Russians stood still. Slowly the lieutenant raised his right hand to the fur cap. It was as if he was paying tribute to the three Germans for their courage, their help, their humanity. […] The snow-covered land no longer lay as blank leaves under the grey sky. The German soldier boots had written a message in the snow.”

Two more years of siege lie before Boris and his fellow citizens, but in Boris an inner transformation has taken place, he has grown up and is no longer full of hatred: “’I am changed’, Boris thought again, for he no longer felt hatred and could therefore think of peace. Just about a week ago he – like everyone else in Leningrad – constantly felt a wild hatred for the Germans. It was this hatred that had often helped him to swallow the tears, and it had given him strength in everything he had experienced: the air raids, the fires, the dead in the snow. But was it possible to rebuild the debris with it? The meeting in no man’s land had taught Boris that there were good Germans. [...] Wasn’t it a miracle that you could lose your hatred in war? [...] Boris now thought of the Russian soldiers and the German soldiers on the nearby front. ‘Lord, have mercy on them,’ he prayed quietly.”2

Boris continues to refuse to be evacuated, although his mother and uncle Vanya aim for evacuating him. His mother finally accepts his decision to stay in Leningrad. Further deprivation, hunger and death of acquaintances are part of everyday life in Leningrad – also for Boris – until the city is finally relieved by Russian troops in 1944 and a train of German prisoners of war passes through Leningrad. •

1 Jaap ter Haar, Boris, published 1 January 1994 by Harcourt Brace & Co (first pub- lished 1966) ISBN-10: 0153022329, ISBN13: 9780153022326; later edition: The Ice Road, published 1 May 2005 by Barn Owl Books, ISBN 1903015383 (ISBN13: 9781903015384)

2 ibid.

Jaap ter Haar

dk. Jaap ter Haar was born on 25 March 1922 in Hilversum in the Netherlands. After graduating from high school in 1940, he initially worked as an office clerk. After the German occupation of Holland he moved to France and joined the Resistance. After the Second World War he volunteered for military service in the Royal Navy of the Netherlands. Later he became a correspondent for overseas radio stations. In his spare time he was already active as a writer and finally made writing his main profession in 1954. His books for children and young people became world-famous and were translated into many languages. Beside “The world of Ben Lighthart“ his young adult novel “Behalt das Leben lieb“1 is one of the most widely read books he has written. Jaap ter Haar died on 26 February 1998 in his Dutch home town of Laren.

1 Jaap ter Haar. “The world of Ben Lighthart“ (Behalt das Leben lieb) ISBN-13: 978-0440096849