75 years after May 1945 – more questions than answers

by Karl-Jürgen Müller

The seventy-fifth anniversary of the unconditional surrender of the German Wehrmacht in the Second World War has given rise to numerous statements and analyses worldwide. This is no surprise. The topics and questions concerning the history of the Second World War, its causes, course and end, as well as its significance for post-war history and for our present are highly diverse and complex. As a rule, it is the perspective that determines what is picked out of the diversity. Also the following article can touch only a few aspects. Aspects which seem particularly important to the author today. There is no need to emphasise here that it is always a blessing when an inhuman political system such as the National Socialist regime comes to an end and when wars can be ended.

Searching in Wikipedia for “Bedingungslose Kapitulation der Wehrmacht” [Unconditional Surrender of the Wehrmacht], one finds the following entry at the beginning of the detailed article: “The unconditional surrender of the German Wehrmacht was a declaration of the Wehrmacht at the end of the Second World War. It contained the agreement to end the combat operations against the Allied forces. The capitulation was signed in the night of 7 May 1945 in the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Forces in Reims after unsuccessful attempts for negotiations from the German side on 6 May and came into force on 8 May. It marked the end of hostilities between the National Socialist German Reich and the Allies. Some German units, however, continued with combat operations against Soviet troops. In order to ensure that the capitulation was also signed by the commander-in-chief of the Wehrmacht, Wilhelm Keitel, and the chiefs of the German navy and air force, it was agreed to ratify it. The German delegation flown in from Flensburg signed the document of surrender on 8/9 May at Red Army headquarters in Berlin-Karlshorst.”

These few sentences alone give rise to interesting questions. After Adolf Hitler himself had taken his own life in the “Führerbunker” (air raid shelter used bei Hitler during Second World War as headquater) in Berlin on 30 April 1945 and the new leadership of the Reich had moved from Berlin to Flensburg, the Wehrmacht leadership apparently believed until 6 May that they could “negotiate” with the Western powers (USA, Great Britain and France) and come to a separate agreement.

Why did parts of the Wehrmacht leadership believe that

they could continue the war against the Soviet Union?

The Western Powers did not discuss this, just like it had been agreed upon beforehand in the conferences of Germany’s opponents. They demanded “unconditional surrender”. In view of the obvious military defeat, this was signed on 7 May by Colonel General Alfred Jodl, the head of the Wehrmacht command staff, at the headquarters of the Western Allies – but not by all commanders of the armed forces. And: “Some German units continued the fighting against Soviet troops […]” And: The leadership of the Red Army demanded a ratification of the surrender by the commanders of all German units. It was no longer Jodl, but General Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, Chief of the High Command of the Wehrmacht, who headed the German delegation that signed the second instrument of surrender on 8/9 May 1945 at Red Army headquarters.

How are these individual events connected? What led parts of the Wehrmacht to believe that they could end the war with the Western powers but continue the war against the Soviet Union? In May 1945, the idea turned out to be a phantasm – especially the Commander of Allied forces and later US President Dwight D. Eisenhower was strictly against it; for he felt obliged to the results of the previous conferences of the Allies. Nonetheless, at the end of the war, leading circles in National Socialist Germany obviously thought mistakenly that they could gain support from the Western powers in the war against the “Bolshevik” Soviet Union.1

Is history used as a weapon to fight conflicts of the present?

Alexander Rahr worked for the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Auswärtige Politik [German Council on Foreign Relations] (DGAP) for 18 years and until 2012 was programme director of the society’s Berthold Beitz Centre, focusing his work on Russia, Ukraine, Belarus and Central Asia. From 2004 to 2015 he sat on the Steering Committee of the Petersburg Dialogue, a high-ranking regular meeting of representatives from politics, business and society from Germany and Russia. Since 2012 he has been project manager of the German-Russian Forum. There he is in charge of the Potsdam Meetings and the working group Common Region Lisbon-Vladivostok. 2012–2015 he was advisor to the President of the German-Russian Chamber of Commerce Abroad. He is a member of the Russian Valdai Club. Since 2014 he was deputy chairman, then member of the advisory board of the Association of the Russian Economy in Germany. Since 2015 he has been an advisor for EU affairs of Gazprom in Brussels. He is the author of numerous books on Russia, including a biography of Mikhail Gorbachev (1985) and one of Vladimir Putin (2000). An interview with Alexander Rahr was published in May 2012 in the Russian newspaper “Komsomolskaya Pravda”. Several of his statements have triggered sharp reactions in Germany. For example he had said: “The Americans amputated the Germans’ brains.” Or: “The West is behaving like the Soviet Union”.

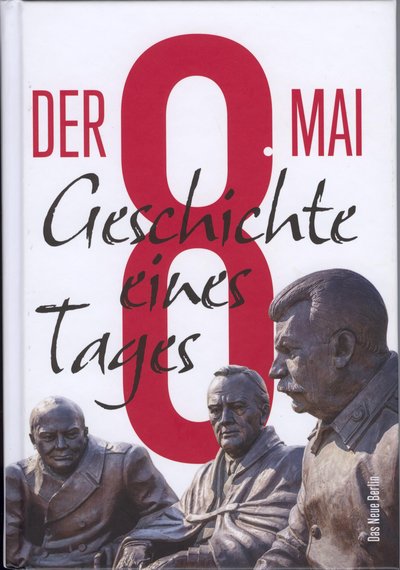

In view of the seventy-fifth anniversary of 8/9 May 1945 he published a new book: “Der 8. Mai. Die Geschichte eines Tages” [May 8th – The History of one Day]. In this book, contemporary witnesses – German, American and Russian – who personally experienced 8 May 1945 have their say. They tell of their experiences at that time.

In an interview with the Russian website Sputnik on 8 May 2020, Alexander Rahr is asked about the fact that Russia is accused of instrumentalising history. He answers: “8 May, or 9 May for Russia, is forever part of the historical memory of mankind. At that time a new world began. Today this day is unfortunately being instrumentalised – on both sides. History is used as a weapon to fight out conflicts of the present. It’s frightening”.

Did the Americans prevent a common historical narrative?

Further down in the interview, Rahr becomes more precise: “One should have developed a common historical narrative in 1990 after the fall of the Berlin Wall, when East and West were in each other’s arms. Actually, Western Europe and Russia were prepared to do this. But unfortunately the Americans came in our way, who, for geopolitical reasons, began to stir up conflict in Europe with Russia, to expand NATO eastwards and thus to keep a hold on Europe’s security policy”.

Indeed, the focus on Second World War, intensified since the escalation of the conflict between Russia and the USA, has become the subject of intense political debate. Politics wants to define what has happened in history. The US government has positioned itself, the EU and especially the governments of some Central and Eastern European EU members have also positioned themselves – and representatives of Russia have done so as well.

Sergey J. Nechayev, the Russian Federation’s ambassador to the Federal Republic of Germany, made another statement on 8 May 2020 in the German newspaper “Junge Welt”: “We must note with regret that recently there has been a growing number of political forces raising their heads which want to radically revise the causes, progress and results of the war, question the decisive contribution of the Red Army and the Soviet people to the victory over Nazism and blame the Soviet Union for unleashing the conflict. These forces set themselves the goal of rewriting history, they do not stop at lies and forgeries, nor do they stop at demolishing monuments and memorials to Soviet soldiers.” (Translation Current Concerns).

Whoever reads the public speeches and statements 75 years after the unconditional surrender of the German Wehrmacht cannot help but feel that history is indeed looking for arguments for the politics of the present. This is not to be rejected on principle, especially not when politics serves the people – and if it does not bend the truth. But that is not always the case.

Is Germany’s tie to the US really a good thing?

Here are just two examples of many: The “Neue Zürcher Zeitung” published an interview with the German historian Heinrich August Winkler on 8 May 2020. He argues that Germany’s tie to the West, to the US – of West Germany before 1990 and of Germany as a whole after 1990 – was the most important lesson of the World War. He also quotes Jürgen Habermas, who in 1986 wrote (mutatis mutandis) that “the opening of the Federal Republic to the culture of the West was the most important intellectual achievement of his generation”. The “success of the second German democracy”, according to Winkler, had “a lot to do with the fact that democracy in the Federal Republic, unlike in the Weimar Republic, was in many ways deliberately oriented towards the example of Anglo-Saxon democracy”. On the other hand, Winkler also said that “in parts of the East German population […] the older, German-national view of history was able to live on unchallenged”. The result: “This is why the AfD [the political party Alternative for Germany] is relatively strong in the East: it appeals to an attitude of German-national defiance.” Winkler calls for “ethics of responsibility” in dealing with Russia: For this reason, “neither in the Baltic states, Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia nor anywhere else in eastern Central Europe should the impression be given that we are making decisions with Russia over the heads of these countries”. Winkler adopts the narrative style of the governments of these states, which is rejected by the Russian side: “Before the Soviet Union was invaded by Germany in 1941, it was a partner of the German aggressor through the Hitler-Stalin Pact of 1939. The memory of that pact continues to haunt our neighbouring countries”.

There would be a lot to say about Heinrich August Winkler’s position. Here only so much: A price of Germany’s “ties with the West”, its membership in NATO, has led to the fact that Germany today is involved in armed conflicts worldwide and, in 1999, with the war against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, for the first time since the Second World War, was again involved in a war of aggression in Europe in violation of international law – according to the Nuremberg Trials of 1946 the most serious of all war crimes. In his classic from 1997, “The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives”, Zbigniew Brzezinski has openly described the means by which the USA has maintained its hegemony and the vassal status of its allies in Europe. Germany had declared this status as a reason of state.

Is the EU a peace project?

The second example is the speech of the German Federal President Frank Walter Steinmeier on the “75th anniversary of the end of the Second World War”, which he gave in Berlin on 8 May. The Federal President also mentioned his lessons from the war. He took up the widespread German formula after the end of the war, “Never again war”, but shortened it to the two words “Never again” and then said: “But for us Germans in particular this ‘never again’ means ‘never again alone’. And this sentence is nowhere so true as in Europe. We must keep Europe together. We must think, feel and act as Europeans. If we do not hold Europe together, also during and after this pandemic, then we will have shown ourselves not to be worthy of 8 May. If Europe fails, the ‘never again’ also fails”. Shortly afterwards he also made it clear what he does not want: “Today, we must liberate ourselves. Liberate ourselves from the temptations of a new brand of nationalism”. The President has chosen a florid language. Most likely, by “Europe” he means the EU. What exactly he means by “nationalism” remains open. Does he also mean those who stick to the idea of sovereign, free and democratic European nation and constitutional states? Here it must be remembered that the supranational Europe that emerged after 1945, from the European Coal and Steel Community in 1952 to the European Community EC founded in 1967, from which the European Union EU developed in 1993, while it was associated by some with the idea of peace, was essentially a product of the Cold War and distrust of Germany. It was the EU which, with its eastward expansion (following NATO’s eastward expansion) after 1990 and then, above all, with its association agreements with Eastern European states such as Ukraine, helped to provoke the conflict with Russia. The Federal President is omitting facts which he himself was involved in.

Are there lessons after May 1945?

Are there serious lessons from May 1945 that have actually been learned? The answer cannot be one-dimensional. It is better to speak of a scale. In the one pan are the countless wars after 1945 – the list is very long2, and these wars have cost the lives of at least 25 million people worldwide. In this pan lie the many international crises and conflicts, many of them still unresolved today, the hegemonic aspirations of great powers, an unjust world economic and financial order, today’s war propaganda, enemy images, prejudices, computerised war “games”, mental neglect and everyday violence.

But there is also the other bowl: the attempts to codify international relations in international law, the essential substantive provisions of the UN Charter – above all the sentence in the preamble: “We, the peoples of the United Nations, determined to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war …”. In this bowl we find the international human rights pacts, the attempts to build a culture of peace, equality and international understanding worldwide, the many approaches to peace education for the young generation. This bowl contains the knowledge of human social nature.

To which side the scales tilt is decided anew every day.

“I know war. This is why I want peace”

Franz Josef Strauss, frequently attacked, wrote in his memoirs: “I know war. This is why I want peace”3. One should have believed him. Just like many other personalities from the war generation who took on responsibility after the war: in business and society, but also in politics. Especially in Germany in the West and East. Many of those born after the war did not do justice to their parents. They saw themselves as something better, only to take part in new wars again after 1990 without sufficient immune defence. This is no less true for those people who still find it difficult to admit to German injustice in war.

Still many research questions

The scientific research results on the causes, the course and the consequences of the Second World War fill entire libraries. Nevertheless many questions are still unanswered. It is to be hoped that all archives will be opened, that all questions will be dealt with in a dignified and objective manner and that research can be depoliticised to a certain extent. Politics will probably decide whether, how and when this is possible.

Certainly correct is the decisive conclusion of the survivors after the war: “Never again war!” But this is actually true even before a war and should have been a guiding principle for all people throughout human history. Even today we are still far from this. The reasons for this are manifold. The problem of striving for power is probably the central problem. This cannot be pointed out often enough. But humanity can also work on the solution of this problem. •

1 In this context, passages such as the following from an article by the historian Ulrich Schlie published in the German journal Cicero on 8 May 2020 with the title “Kriegsende am 8. Mai 1945 – Die Geschichte kennt keine Stunde Null” (End of the war on 8 May 1945 – History does not know a zero hour) are interesting: “Never have tensions in American-Soviet relations been greater than in April and May 1945. Molotov had paralysed the San Francisco Conference, which had been in session since 25 April by his inflexible stance, insisting on the demand for a Soviet veto and on voting in the Security Council. Only when Truman sent the former Roosevelt confidant Harry Hopkins to Moscow for negotiations from 26 May to 6 June did he succeed in overcoming the deadlock in Soviet-US relations. (https://www.cicero.de/kultur/kriegsende-1945-achter-mai-zweiter-weltkrieg-nationalsozialismus-geschichte-stunde-null)

An overview of the (all failed) German attempts to come to an agreement with the Western powers – directed against the Soviet Union – before the end of the war in 1945 can be found in an article by Hansjakob Stehle, “Deutsche Friedensfühler bei den Westmächten im Februar/März 1945” (German peace sensors among the Western powers in February/March 1945), in the Quarterly Bulletins of Contemporary History, issue 3/1982, published by the Munich Institute of Contemporary History.

2 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Outline_of_war#Wars

3 Strauss, Franz Josef. Die Erinnerungen (The memories). Siedler Verlag Berlin 1999, p. 42

“Let us work for peace“

What is asked of young people today is this:

do not let yourselves be forced into enmity and hatred of other people,

of Russians or Americans,

Jews or Turks,

of alternatives or conservatives,

blacks or whites.

Learn to live together, not in opposition to each other.

As democratically elected politicians, we, too, should heed this time and again and

set a good example.

Let us honour freedom.

Let us work for peace.

Let us respect the rule of law.

Let us be true to our own conception of justice.

On this 8 May, let us face up as well as we can to the truth.

This was how Federal President Richard von Weizsäcker concluded his speech on 8 May 1985