Just rhetoric, or discernment?

Shortage. The word had disappeared from the developed industrial countries’ economic vocabulary since the end of the Second World War. In the midst of the coronavirus crisis, it is experiencing a strong comeback. Lack of hospital beds, but also of masks, disinfectants, tests, respirators and drugs...

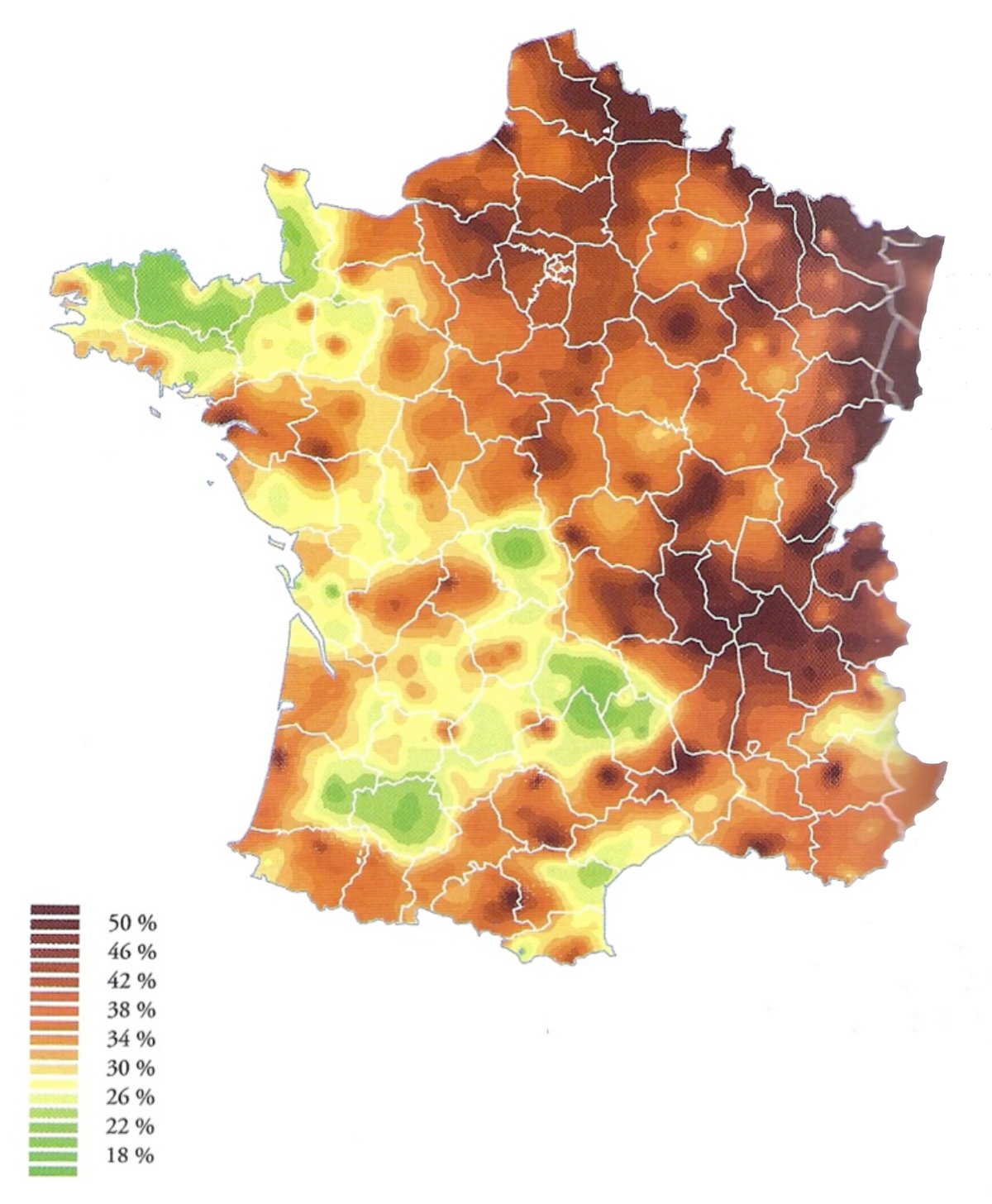

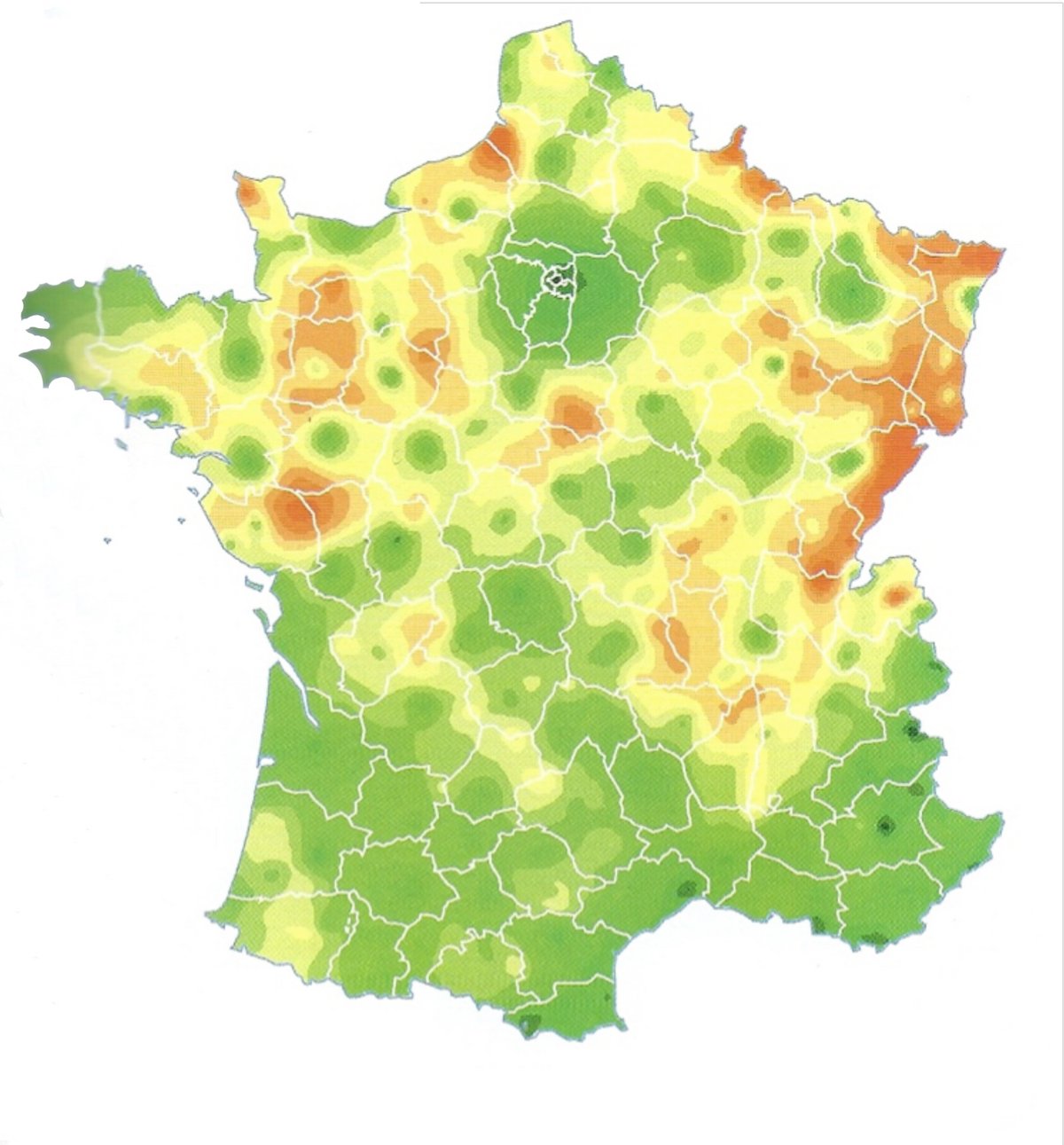

COVID-19 has highlighted these dramatic deficiencies. In France, they are the result of a deliberate and long-term policy of relocating industrial production and deindustrialising the country. Since the mid-1970s, the share of manufacturing industry in the French economy therefore has halved: it now accounts for only 10% of domestic wealth. And the slight changes in recent years have not made it possible to seriously reverse the trend.

The state’s withdrawal: destruction of jobs

and services of general interest

One example among many others is the closure of a large mask factory in Plaintes in the Côtes d’Armor at the end of 2018, for which a relocation was planned. Before, in 2010 the French company Spérian had already switched to the American flag of Honeywell.

The machines could produce up to 20 million FFP1 and FFP2 masks per month. In 2005, 6 million euros were still invested by the public authorities and this enabled massive production in 2009, at the time of the H1N1 virus, before the state decided to withdraw.

At the time of the closure, the conveners from CGT and CFDT of the factory had asked Emmanuel Macron and the Minister of Economy, Bruno Le Maire, to save the company. Without success at the time.

In addition, the management had taken great care to destroy the eight production lines so that they would not fall into the hands of a competitor. Recently, it was heard that trade unionists and affected communes are trying to revive the company.

A similar tragic scenario is taking place at the Luxfer plant in Gerzat (Puy-de-Dôme), with the Anglo-American group Luxfer Gas Cylinders acting as liquidator. Until the spring of 2019, French employees were producing medical oxygen cylinders there – the last to be manufactured in France and even on the entire continent. Once again, the same incapacity of the state, but also the same willingness to resume production on the part of the workers, who still do not want to give up. All the more so because this material has gained crucial importance for revival, given the soaring demand.

“Even in a wartime economy, it is difficult to mobilise non-existent capacities, evaporated know-how and to fill the gaping holes of specialisation,” remarked the economists Elie Cohen, Timothée Gigout-Magiorani and Philippe Aghion in a column in Les Echos (31 March 2020) on this massive deindustrialisation. They remind us that Germany, for its part, has not stopped increasing its production capacity: German gross exports of tests that can now be mobilised for COVID-19 amount to almost 2 billion euros per year, compared with almost 200 million euros in France.

Severe dependencies

The pharmaceutical industry, for its part, is at the forefront in the dismantling of production lines. Today, between 60% and 80% of active ingredients are produced outside the European Union, compared with 20% to 30% twenty years ago. Not to mention France itself. The European Commission says today that it is considering a “reassessment” of production chains within the EU. But then?

India is the biggest supplier of generic medicines and vaccines, meeting 20% of world demand. But this quest for financial efficiency leads to dangerous dependency, all the more so as the subcontinent itself is affected by the coronavirus.On 4 March 2020, for the first time in its history, India decided to halt exports of 26 active ingredients such as paracetamol, antibiotics and antivirals. The country also wanted to protect itself from the no less severe dependence in which it finds itself: India imports almost 70% of its active ingredients, which are at the heart of pharmaceutical production, mostly from China. Under pressure, particularly from the United States, Prime Minister Narendra Modi finally released 13 medicines and additives on 7 April.

This fragmentation across several countries of production is all the more dangerous because the corporations, from Sanofi to Novartis, believe that the data on the origin of their products they are zealously protecting are manufacturing secrets.

After several warnings of supply disruptions for Europe, the French company Sanofi launched on 24 February the creation of a company in order to bring together the six European plants producing active ingredients. Solid consolidation?

Short-term profit optimisation for a few

instead of long-term security of supply for everyone

In reality, the concern intends to list this future company, which ultimately only holds 30% of the capital, as a subsidiary to the stock market. In this way, you can discreetly say goodbye to this unit. While public institutions like BPI-France (the French reconstruction credit institution KfW) are welcome to participate in the financing round of the new company, it is very likely that foreign funds will also be happy to participate to influence its decisions.

By disassociating their production in this way, the manufacturers have reduced their costs, but at the same time made their production chain extremely vulnerable. And not just in the pharmaceutical industry. Another activity that is closely linked to the industrial history of France is currently paying its price: the automotive industry.

Carlos Tavares, president of PSA (Peugeot-Citroën) can boast that he “only” has 300 Chinese suppliers out of a total of 8,000, which is enough to block the production chains in Poissy and Rennes. In this case China focuses on low value-added production, which is 4% of the price of building a vehicle in France. Overall, however, these parts represent 20%, and even 50% for small mechanical and plastic components. Under these conditions, there is no point in continuing to manufacture bumpers in Europe if screws and nuts are missing so that the cars can leave the factories.

Surprising changes

In the current crisis all of this leads to some surprising changes in how we do it. Philippe Varin, former head of Peugeot-Citroën (PSA), who had decided to close the Aulnay-sous-Bois site, now is the president of the lobby of the French Federation of Industrialists and believes that the crisis “can take the character of a chance because it enables the resumption of production in France”.

Another turning point: Laurence Daziano, a researcher at Fondapol, who calls herself a “liberal and European think tank”, demands the “reconstruction of French industry” in Les Echos (7 April) with a “steering and financing function” for the state that is asked to “participate in strategic industries with a stake up to 10% or 15% in the capital of all French strategic industries.”.

But the most spectacular rhetorical U-turn can be found in the Elysée Palace. On 13 April, Emmanuel Macron pleaded for “the reconstruction of France’s independence in the areas of agriculture, health, industry and technology”, not without recalling his mantra: “more strategic autonomy for our Europe”. “Our Europe”, in this case the EU, is still based on the free movement of goods, services and workers. And capital.

As things stand, European heads of state and government, particularly the French, president, do not question this fundamental and existential dogma in any way. The gap between rhetoric and reality could therefore widen. But also become more and more visible. •

Source: ruptures-presse.fr/categorie/deutsch/ 26 May 2020

(Translation Current Concerns)