A hundred years ago: End of war, general strike, pandemic

Switzerland in crisis – direct democracy as the way to go

by Dr rer. publ. Werner Wüthrich

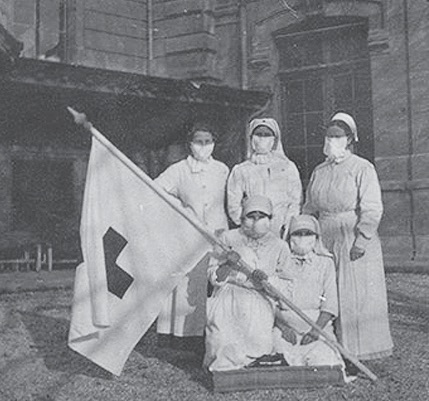

The coronavirus did not cause the first pandemic with which the Swiss population was confronted. At the end of the First World War – in 1918 – it found itself in a similar, but far worse situation than today. Even then, the flu was underestimated – with serious consequences.

After four long years, the war had ended in the autumn. The food situation was poor, hunger was rampant, and inflation was not under control – even in Switzerland, which had fortunately been spared from fighting. Some countries were in turmoil: in Russia, the revolution had taken place, and Lenin had begun – as announced – to establish the “dictatorship of the proletariat” – as Swiss citizens returning from Russia reported. Councils of workers and of soldiers formed in German cities. In Berlin, a civil war broke out between workers’ militias, units of the Reichswehr and the Freikorps. Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht were murdered. The Kaiser had fled to Holland. In Munich the Räterepublik was proclaimed (which was not able to stay in power for more then a few days). In Vienna the Danube monarchy was dissolved and a republic established. There was shooting, too. Vorarlberg wanted to join Switzerland by means of a referendum. In Budapest a soviet republic was established and lasted for several months. These were turbulent times.

Serious strikes took place in many countries – including Switzerland. On 11 November 1918 the trade unions called a general strike throughout the country. 250,000 strikers faced 90,000 soldiers who had been called out by the Federal Council to serve as a security force. Only a few weeks before, the strikers had been wearing the same uniform. In the summer, a wave of influenza had broken out worldwide. Those responsible on both sides knew that the Spanish virus, as it was called, was everywhere. But everyone had underestimated its danger.

Today, there is extensive literature available on this key event in Switzerland’s history. In the following paragraphs, the militiamen of the then Ordnungsdienst from the Cantons of Thurgau and Glarus will have their say. They experienced the mass marches and the pandemic with its catastrophic effects directly.

The following reports (“Report from Glarus” and “Report from Frauenfeld”) give a picture of the events and are taken from the books “Geschichte des Landes Glarus” by Jakob Winteler (1954) and “Geschichte des Kantons Thurgau” by Albert Schoop (1984).

Schoop describes the political situation in autumn 1918 before the strike as follows: “On 7 November, the anniversary of the Russian Revolution, many people in Switzerland expected new revolutionary action with a precise programme which would, in addition to the creation of workers’ councils, provide for disarmament of the ‘bourgeoisie’, dissolution of the bourgeois parliaments, takeover of political power by the organised working class, as well as the overthrow of the bourgeois government and establishment of the proletarian dictatorship. (“Thurgauer Zeitung”, 18 October 1919, quoted according to Schoop, p. 258)

The SP Switzerland board had decided – against the vote of its president – to commemorate the anniversary of the Russian October Revolution of 1917 with rallies throughout the country. The Federal Council mobilised troops as a precaution. The trade unions called on the national government to withdraw the military, in the form of an ultimatum. When the government did not respond, the “Olten Committee” (strike management) extended the warning strike already called in Zurich to a nationwide general strike. In Thurgau, a cantonal committee called for the formation of local armed forces. (Schoop, p. 252)

How the general strike was carried out

Report from Glarus: “Regiment 32 with the Glarus Battalion 85 also belonged to the deployed troops which were entrusted with the protection of peace and order.

On 11 November, a Monday morning, officers and crews were mobilised by chiming of bells and rataplan of drums and many of them arrived as soon as in the late evening hours, having made use of all conceivable means of transport. Mobilisation continued throughout the night, so that the unit was ready for action by the following morning. On Wednesday, the battalion marched to Kaltbrunn to be transferred onto the train to St. Gallen, where, greeted with joy by the population, it took over its orderly service, which proceeded without incident. The city insisted on giving each soldier an honorarium of 20 francs. (Winteler, p. 617)

The deployment of the three Thurgau battalions 73, 74 and 75, was not quite as pleasant. They were deployed in the city of Zurich.

Report from Frauenfeld: “What had the Thurgau troops experienced during their orderly service? The infantry marched to the barracks yard in Zurich at dawn on 9 November, from where they were assigned special duties. ...] Already in the late morning of the same day, the Battalion 73 had to march to the Paradeplatz in a column of eight and with sharply loaded weapons, as a large forbidden demonstration was to be had to be there. The Thurgauers were received with whistling, bawling and swearing. ...] The Thurgau soldiers set up patrols and sentries in the streets and protected the public buildings, especially the barracks, to which the Zurich government had withdrawn. The crew kept calm and level-headed and did their duty, but felt that this service in a turbulent, fermenting city, where civil war was within the realm of possibility, was the most unpleasant and psychologically stressful event of their service during the war”.

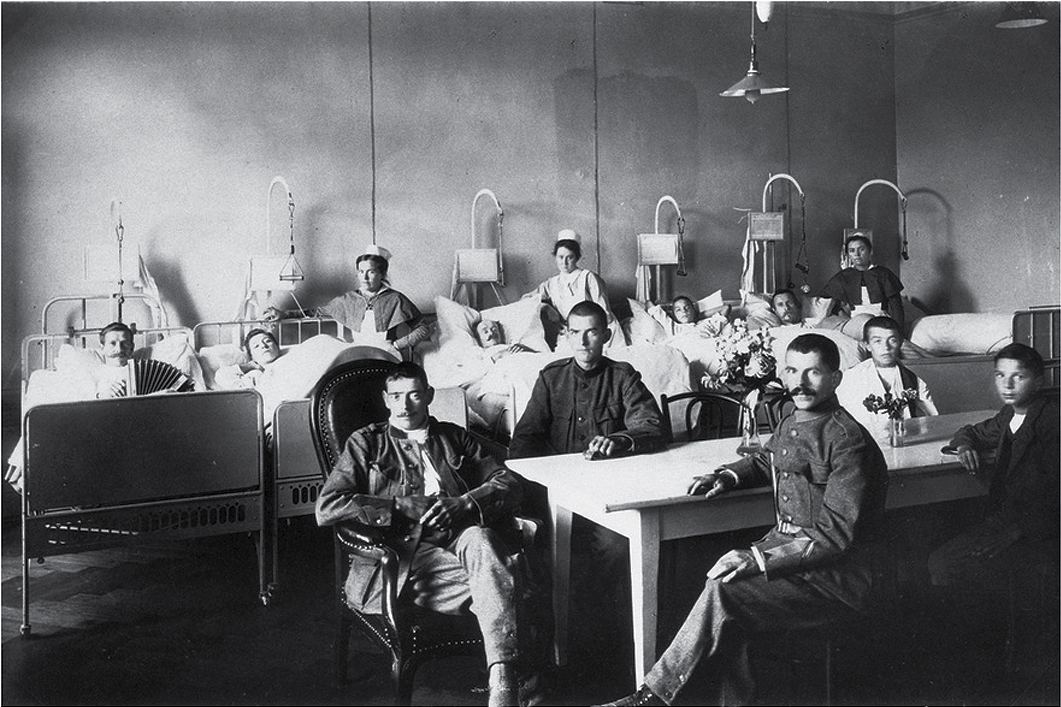

The flu was present from the very beginning: “The flu spread more and more, it seized the men in the army by the dozen. The Tonhalle and many gymnasiums had to be equipped as emergency hospitals, and there were some units which moved out with only half their men.

And there was shooting: “The Lucerne Fusilier Company I/42, weakened by the flu and with only 55 men left, came to Fraumünsterstrasse to clear the square, but it was too weak; it was surrounded, insulted, trapped and could only free itself by firing a few volleys into the air. Rebound shots injured three civilians; soldier Vogel lost his life by a pistol shot fired from the crowd”.

“The frightened urban population gained confidence through the presence of the troops and began to cosset the soldiers. A variety of gifts, large and small, piled up in the guardhouses. Slowly calm and reason returned, and with the end of the strike life in the city returned to normal. (Schoop, p. 246 – 251)

The general strike was mainly acted on in the larger cities of German-speaking Switzerland. However, the marches took different courses in different places. Some troop commanders were reluctant to carry out their mission – others less so, such as in Zurich. In Grenchen, soldiers guarding the station and feeling threatened shot three workers. On the other hand, there were no incidents in St. Gallen or Bern.

Everyone had underestimated the pandemic

The pandemic began in the summer of 1918. It was initially considered relatively harmless. The second, more violent wave occurred while the conflict between the trade unions and the state government was coming to a head. Not all cantons kept such precise statistics as the Cantons of Glarus and Thurgau. It can be assumed that in the few days of the strike and in the weeks following it, several thousand people (soldiers and workers) lost their lives as a result of the pandemic.

Looking back today, the question arises as to what stand parliament took and why the Federal Council did not ban the strike and the associated mass marches and demonstrations simply for epidemiological reasons, as it has done today. Some of the parliamentarians were transported to the Federal Parliament Building in military vehicles. The majority of them approved the state government’s course of action (the Council of States did so almost unanimously), and described the strike “as an irresponsible frivolity against public health” and demanded that the issues at stake be resolved on the basis of law and the constitution (Schoop, p. 250).

In turn, the union leaders accused the Federal Council and the army leadership of having done far too little to protect the population and the soldiers. The mood was politically so heated and hostile that a ban would probably have led to a further escalation. It is questionable whether the trade unions would have complied with such a ban at all.

Abandoning of the strike and return home of the soldiers

In this dangerous situation, on Wednesday 14 November the Federal Council gave the Olten committee an ultimatum to stop the strike immediately. The strike management gave in, so that the soldiers from Thurgau and Glarus could return to their homes. On Friday, 16 November, work was resumed in most places. – We can only speculate as to what would have happened if the strike management had rejected the ultimatum.

Report from Frauenfeld: “Nobody was happy about the dismissal. Thurgau Regiment 31, which reported a sickness absence rate of 1,180 men on 19 November, had returned home with heavily thinned ranks. […] It mourned the death of 46 comrades. In the whole canton, 20,837 cases of sickness [including those in the population] were reported, 234 of which proved fatal.”

“On 15 November, the Grisons‘ Battalion 93 was stationed in Frauenfeld, the 6th Division headquarters. Their losses were particularly heavy. When they returned to Chur five days later, they left behind over 200 flu-sufferers.” (Schoop, p. 252)

Report from Glarus: “The return of the battalion for demobilisation on 20 November gave a distressing impression, as almost half of the men, fallen ill with the at first seemingly harmless flu, were laid up in the hospitals in St. Gallen, Uznach and Glarus. Within a single week, the troops had to record over 300 absences. Since the summer, the epidemic had already spread across Europe and had subsequently claimed numerous victims, also among the civilian population. [...] During its twelve-day strike service, Battalion 85 had 22 of its Glarus members to mourn as victims of flu, ... 65 men in total in Regiment 32.

“The epidemic caused numerous disturbances. Not only were the church fair events in autumn banned, but social life came to a complete standstill. Schools remained closed; even at Christmas the celebration of Holy Communion was prohibited in most Protestant churches.“ (Winteler, p. 617-618)

Report from Frauenfeld: “The hoped-for normalisation was a long time in coming. It was not until January 1919 that assemblies were allowed to be held again on the territory of the Canton of Thurgau. The ban on dancing remained in force yet for a while.

The pupils at the Thurgau cantonal school, which had been provisionally set up as a military hospital for flu patients, as well as those of the primary and secondary schools, attended classes once again after a long interruption of three months“. (Schoop, p. 254)

The supply situation improved only slowly. Rationing continued for months after the end of the war. The bread ration card was only abolished in September 1919. The population of Thurgau was also aware that the conditions in neighbouring countries were much worse: „The rural population of Thurgau participated strongly in the Swiss relief operation for the suffering city of Vienna, which was supplied with 420 tonnes of food, conveyed there in a special train accompanied by Thurgau soldiers. The following winter, Viennese children travelled to Switzerland for recreation, many of whom found sympathy and help in the hospitable Thurgau. (Schoop, p. 254) In March 1919, the Federal Council promised the delivery of 5,000 heads of cattle to Northern France and Belgium. Therefore, no more beef was allowed to be eaten in Thurgau.

How can such a serious national crisis be resolved?

These reports show impressively how strongly the events surrounding the general strike and the flu pandemic affected civil and political life. Switzerland was deeply divided. It was probably the worst state crisis in the history of the federal state founded in 1848. How was it overcome?

Despite strong radicalisation, the Social Democrats made it clear that controversial issues can be resolved democratically without violence. They called a party conference: The report from Frauenfeld comments: “After bitter disputes at the Extraordinary Party Conference of the Social Democrats in Basel, a strong majority of delegates spoke out in favour of the Swiss party leaving the (socialist) Second International and joining the (Bolshevik) Third International, but opponents among them, including the former pastor of Arbon, Karl Straub, did not give up and demanded a written inquiry. […] Throughout Switzerland, accession was clearly rejected with 8,722 yes against 14,612 no.” (Schoop, p. 259-260). – A strong minority left the party afterwards and founded the Communist Party of Switzerland.

Citizens push through most of the

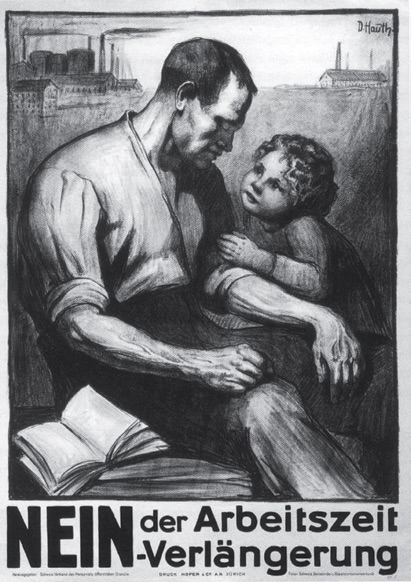

demands from the general strike

There were also numerous votes at the political level. The trade unions had gone on general strike with a list of eight demands, all of which points were largely justified. Almost every point was decided at the ballot box: as early as 1918 on the popular initiative to introduce proportional representation (Yes). This was followed in 1919 by the vote on early elections according to the new system (Yes). Also in 1919, a parliamentary resolution introduced the 48-hour week in factories. In 1920 a vote was taken on the introduction of the 48-hour week in the railways (Yes) and in 1921 on the popular initiative to abolish military justice (No).

In 1922 the SP popular initiative was put to the vote, which demanded that the property-owning class pay the war debts by means of a one-off property levy. This was rejected by 87 percent of nays, with 86 percent of the eligible voters participating. In 1924, the people rejected a federal law that would again extend working hours in times of crisis. On May 24, 1925, voters rejected the popular initiative (Initiative Rotheberger) for the establishment of the AHV because the method of financing did not suit. On 6 December 1925, voters did approve the constitutional article on the establishment of AHV and IV. Four plebiscites on an agricultural policy that would better secure food supplies even in crises then followed in the course of these years. (During the Second World War, the supply situation was therefore much better) – It was only the women who still had to wait. Their voting rights were not to be voted on until many years later. In 1959 these were still clearly rejected by the Swiss men, in 1971 They were accepted. In several cantons women received the right to vote earlier. (Linder 2010)

Switzerland had found its way

The political mood and also politicians themselves already changed in the twenties, so that the country became more stable. This is because the citizens are directly involved and everyone has a voice - in the parties, the associations and at all political levels. Here are two examples:

Ernst Nobs from Zurich, as editor-in-chief of the largest social democratic daily newspaper “Volksrecht" ("People’s Law”), protested in the strongest possible terms against the cancellation of the general strike: “This is enough to make you weep! Never has a strike collapsed more shamefully, not under the blows of the opponent, not because of any weakness, not because of the despondency of its own troops, but because of the cowardly, faithless attitude of the strike leadership. (“Volksrecht” of 15 November 1918) Nobs was sentenced to prison by a military court. Years later he was elected to the governing council of the canton of Zurich, he became mayor of Zurich and in 1943 he was the first social democrat to become a member of the Federal Council.

Konrad Ilg from Thurgau was vice president of the Olten committee and had co-organised the national strike. Being a locksmith himself, he passionately championed the interests of workers. He was fond of studying the writings of Pierre Proudhon and the French socialist Jaurès, whose deep humanity impressed him. In 1917 – one year before the general strike – he became president of the Swiss metal and watch workers’ union (SMUV). For twenty-five years he represented the workers’ interests in the National Council.

In 1937 Konrad Ilg approached Ernst Dübi, director of the von Roll company in Gerlafingen and colonel and chief of artillery of the 4th Army Corps. Their talks led to the so-called peace agreement, which put the relationship between employer and employee associations on a new footing. Good faith became the principle in future negotiations, i.e. the trade unions and employers’ associations trust each other and assume that the opposite side has good intentions, and common interests are paramount. Wage agreements were no longer negotiated indiscriminately for an entire industry, but individually for the individual company. Strikes and lock-outs as a means of exerting pressure were dropped, and this paved the way for industrial peace. Many an employer discontinued conducting himself as the “master of the house”, and it worked. Both Dübi and Ilg were given honorary doctorates by the University of Bern. (Wüthrich, p. 190-193) There have been no major strikes since then – until today.

The general strike remained an isolated event

During the great economic crisis of the 1930s, the trade unions took a different approach. They launched a number of popular initiatives and held referendums, each of which they submitted with over three hundred thousand signatures collected in only a few weeks – this was many times the required number. The Federal Council and parliament took heed of their wishes and quickly put them to the vote. Such numbers of signatures were never to be reached again later, even though Switzerland now has twice as many inhabitants, and women have also been able to sign since 1971. Voter turnout was as high as about 84 per cent in each case.

Similar to the situation after the First World War, at the end of the Second World War the question arose as to how the economic order could be reorganised and made more social. In 1943, the SP Switzerland adopted its programme “The New Switzerland” and launched a popular initiative to this end. (Even before the war, parliament had already prepared a draft for new economic articles in the Federal Constitution). However, the comrades were not alone. In the same year, four more popular initiatives with a similar thrust were submitted from other political camps, even though the war was not yet over. After the war, several votes were taken, the course was set and cornerstones were defined for the social market economy in which we live today (Wüthrich 2020).

The present time

Since the general strike of 1918, the people have been able to vote on “almost anything and everything”, and they did so more than 500 times at federal level alone – even in difficult situations (they voted countless times more in the cantons and communes). The result is impressive. Switzerland has developed from a relatively poor country in the 19th century to a prosperous and politically stable country.

Today, however, a fundamental setting of the course is imminent: The EU wants to involve Switzerland more closely in its politics and is calling for a framework agreement that provides for automatic adoption of the law. We are told that the people will still be able to vote, but “Brussels” reserves the right to react with “compensatory measures” if the result of this vote is not in its taste. – What a curious idea.

Switzerland has found its way. Its model gives participation to the people, a voice to every citizen, and shows that things can be done differently. It is a message for peace – and also for the international community. It is therefore shocking and incomprehensible that the Swiss diplomat Thomas Greminger (who, incidentally, did his doctorate on the period of the general strike of 1918) was recently, for no apparent reason, not confirmed as Secretary-General of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe OSCE and that this peace organisation is currently paralysed. The political tensions in the world today are hardly less dangerous than in 1918, and they are increasing.

In a few weeks’ time – on 27 September 2020 – there will be another vote in Switzerland: on the procurement of fighter planes, on paternity leave, on child deductions in federal taxes, on a hunting law that makes it easier to shoot wolves, and on a popular initiative that calls for moderate immigration (limitation initiative).

How exciting politics can be! We should thank our parents, grandparents and great-grandparents who made this politically possible. On our national holiday on 1 August, we commemorate the alliance of the three original Cantons of Uri, Schwyz and Nidwalden in 1291. I think that the great construction work in recent times is also worth remembering! •

Sources:

Greminger, Thomas. Ordnungstruppen in Zürich. Der Einsatz von Armee, Polizei und Stadtwehr, Ende November 1918 bis August 1919. (Order troops in Zurich. The deployment of army, police and city troops, end of November 1918 to August 1919). Basel/Frankfurt am Main 1990

Linder, Wolf and others. Handbuch der eidgenössischen Volksabstimmungen (Handbook of Federal Referendums). Bern 2010

Schoop, Albert. Geschichte des Kantons Thurgau (History of the Canton of Thurgau), Volume I. Frauenfeld 1987

Winteler, Jakob. Geschichte des Landes Glarus (History of the canton of Glarus). Glarus 1954

Wüthrich, Werner. Wirtschaft und direkte Demokratie in der Schweiz (Economy and direct democracy in Switzerland). edition Zeit-Fragen, Zurich 2002, ISBN 978-3-909234-24-0