“The final question will not be whether America or China has won. It will be whether humanity has won.”

Kishore Mahbubani’s latest book on Chinese-American relations

by Johannes Irsiegler

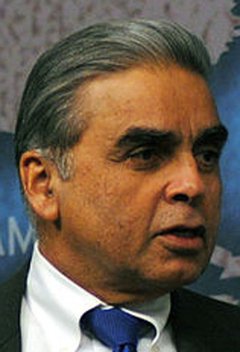

The Singaporean political scientist and diplomat Kishore Mahbubani is known for his publications in which he keeps on calling for more equality in the relations between the West and Asian cultures. As a first step, he wants to arouse interest in the other culture and aims at imparting knowledge about it – a concern for understanding among nations and in the end, for peace. Mahbubani can draw upon a wealth of individual and cultural experience, as he knows both the Western and the Asian world.

His latest book, “Has China won? The Chinese Challenge to American Primacy” is rooted in the tradition of understanding among nations.

A plea for cooperation in times of rising tension

The book deals with the relationship between the two great powers, the USA and China. This is of great importance to readers in all countries, as it is very significant for all of us whether these two powers will be cooperating on issues of global importance, or whether the desire for dominance and, as a consequence, the danger of war will prevail.

The latter is a real danger. Against the backdrop of serious domestic and foreign policy problems, the once sole world power, the United States, is adopting a very irreconcilable and confrontational tone towards China, and, as Mahbubani notes, is doing so across otherwise irreconcilable party lines. In other Western countries, too, there is an increasing number of voices who believe that they must adopt a confrontational tone towards China, as much as possible, to match that of the USA.

The title of the book might be misleading. Mahbubani is not concerned with prophesying the victory of one power or another in global competition. At the end of the book, he concludes: “The final question will therefore not be whether America or China has won. It will be whether humanity has won.”1 Mahbubani reminds that China and the USA together make up only just 25 % of the world’s population. The remaining six billion people on earth expect both powers “to focus on saving our planet and improving the living conditions of humanity, including of their own peoples.”2 For this to succeed, the other party’s concerns must be understood realistically and without ideological blinkers, which also means recognizing one’s own misguided developments that have led into the wrong path of confrontation.

Western ignorance of a culture thousands of years old

For a reader from a Western state, the examples of how Mahbubani describes China are very instructive. Right at the beginning of his book, Mahbubani states that it is a fundamental error if the Chinese Communist Party CCP is perceived primarily as Communist and not as Chinese. In East Asia it is rightly recognized that the foundation of the CCP today is above all Chinese civilization and culture. The C in this context stands for Chinese civilization. The Chinese system of government reflects thousands of years of Chinese political tradition and wisdom. Mahbubani acknowledges China’s great historical achievement over the last thirty years: 1.3 billion people have been taken out of poverty. He states, that the Chinese people have enjoyed more personal freedom under the CCP than any other previous Chinese government.3

Mahbubani characterizes the educated Chinese as very open and thoughtful. “Most Chinese leaders […] are steeped in the classics of Chinese thought. These classics in turn open their minds to a lot of ancient Chinese philosophy – theirs is a thoughtful culture. From this they understand that the greatest mistake for any Chinese leader would be to be rigid, ideological, and doctrinaire. Hence, even though many Chinese leaders reaffirm their commitment to Marx and even Mao, they also know that these examples must be adapted and implemented in a flexible way.”4 The Chinese leadership, Mahbubani says, wants to regenerate its own culture, but without having a missionary impulse towards the rest of the world. On the contrary: “One great paradox about our world today is that even though China has traditionally been a closed society, while America purports to be an open society, the Chinese leaders find it easier than American leaders to deal with a diverse world, as they have no expectation that other societies should become like them. They, unlike Americans, understand that other societies think and behave differently.”5 He points out: “China is probably the least interventionist power of all the great powers.”6

Reflections on democracy

One chapter of the book is dealing with the question whether China should become “democratic”, a demand repeatedly made to China by the West. However, this would first need a discussion of what democracy really is. Mahbubani puts this question into a larger, socio-historical context of China: “The Chinese people fear chaos. It is the one force that in the past brought China to its knees and brought misery to the Chinese people.”7 Especially in its recent history, China has experienced many periods of chaos and instability. This is why stable political conditions have top priority. In case of doubt, the Chinese culture gives priority to social harmony. However, there is also the example of democratic development in Taiwan. According to Mahbubani “it is actually in China’s national interest to allow the continuation of a social and political laboratory to indicate how a Chinese society functions under a different political system.”8 Furthermore, “China could learn long-term lessons from Taiwan on how Chinese people cope with democracy.”9 For this however, the relations must not be disturbed from outside.

Despite a growing antagonism between the two world powers, Mahbubani considers that there is still cause for cautious optimism. “Yet, even though the case for pessimism is strong, one could also make an equally strong case for optimism. If we could marshal the forces of reason to develop an understanding of the real national interests of both America and China, we would come to the conclusion that there should be no fundamental contradiction between the two powers.”10

There is no contradiction between their own interests. On the contrary, Mahbubani even speaks of five “non-ontradictions”.11 Furthermore, “if America and China were to focus on their core interests of improving the livelihood and well-being of their citizens, they would come to realize that there are no fundamental contraditions in their long-therm national interests.”12

According to Mahbubani there is the chance that “the march of reason, triggered in the West by the Enlightenment, is spreading globally, leading to the emergence of pragmatic problem-solving cultures in every region and making it possible to envisage the emergence of a stable and sustainable rules-based order.”13

The ideals of Enlightenment, which embrace humanity, could thus flourish in every culture with its own specific character. This is how Mahbubani understands a thought of the Chinese President Xi Jinping: “Civilizations don’t have to clash with each other; what is needed are eyes to see the beauty in all civilizations. We should keep our own civilizations dynamic and create conditions for other civilizations to flourish. Together we can make the garden of world civilizations colorful and vibrant.”14

For Mahbubani, the ability to understand another culture and learn from it is one of the reasons for the success of Asian countries: “One reason the West can no longer dominate the world is that the rest have learned so much from the West. They have imbibed many Western best practices in economics, politics, science and technology.”15 Why then should the West not be able today to overcome the pressing problems, for example the corona crisis, in a process of mutual understanding and learning from each other?

Mahbunabi’s remarks on the role of Europe, on the question of Hong Kong and Taiwan are very worth considering, but to present them in detail would go beyond the scope of this discussion. Here again he pleads for more understanding and less confrontational thinking in black and white terms.

The only “downer” is that the book has just been published in English so far. However, it is very worth reading. We wish this important political book translations into as many languages as possible, so that the idea of understanding among nations and peace will be widely spread. •

1 p. 282

2 Mahbubani is using the term “Chinese Communist Party” and “Chinese Civilization Party” for CCP (p. 7).

3 p. 172

4 p. 171

5 p. 254

6 p. 148

7 p. 15

8 p. 99

9 p. 99

10 p. 260

11 p. 260

12 p. 281

13 p. 274

14 p. 275

15 p. 11

(picture Wikipedia)

ji. Born and raised in Singapore as the son of Indian parents, Kishore Mahbubani feels close to all Asian cultures. His name Mahbubani is of Persian origin, he can say of himself that he has “cultural connections with different societies in Asia, where half of humanity lives, all the way from Tehran to Tokyo”. (p. 12) His professional career began in 1971 as a diplomat at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Singapore. He worked there until 2004, during which time he was sent to Cambodia, Malaysia, Washington D.C. and New York. He served as Singapore’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations and held the position of President of the United Nations Security Council between January 2001 and May 2002. From 2004 to the end of 2017 Mahbubani, as founding member and first Dean, worked at the National University of Singapore’s (NUS) Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy (LKYSPP) .