The “Buchenwald children” on the Zugerberg

How the “Swiss Donation” helped traumatised young people

by Winfried Pogorzelski

Towards the end of and immediately after the Second World War, Switzerland provided assistance to many war-affected persons in a variety of ways to ease the material and psychological consequences for those affected.1 It was important for the neutral country to stay independent and not to join the relief agency of the victorious Allies, the so-called UNRRA (United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration), which had already been founded in 1943 by the USA, the Soviet Union, Great Britain and China, and, after the end of the war, was taken over by the UN.

The Federal Council gives the necessary impulse as a sign of gratitude

Thus Switzerland organised humanitarian aid and reconstruction assistance even in war-torn Europe. In December 1944, the Federal Council published the brochure “Our people would like to thank” (circulation: 1.5 million), and thus initiated the integration of various relief organisations to form the so-called “Swiss donation for the victims of war”. As a patriotic relief organisation, it was also intended to help overcome Switzerland’s isolation in foreign policy. A fundraising campaign among the population brought in around 47 million francs, with the federal government contributing more than 300 million francs.

In 18 European countries various relief campaigns were carried out-organised and carried out by the Red Cross. For example, children suffering from tuberculosis were brought from Vienna to Davos for recreation; in the German towns of Friedrichshafen and Constance or (Swiss) Kreuzlingen, Switzerland supplied thousands of children with clothing, shoes and food. Hundreds of 4 to 10-year-old children arrived in Switzerland by train from Hamburg, where they were provided with all the necessary care.

Relief and recovery for the traumatised

One special campaign consisted in Switzerland offering the Allies to receive 2,000 children and adolescents from concentration camps for half a year for recreation in Switzerland.2 On 25 June, instead of the expected children, 374 young adults between the ages of 17 and 25 arrived in Basel as most of the children had been killed by the SS under the pretext not being fit for work.

Before that, the young people had been liberated by US troops. They had reached Buchenwald only a few months ago: The SS had driven them from the Auschwitz-Birkenau and Gross-Rosen concentration camps westward into the notorious death marches – leading to Buchenwald, among other places – to prevent their liberation by the Red Army.3

The female adolescents were accommodated in a home in Vaumarcus in the canton of Vaud, the male adolescents on the Zugerberg. They arrived there on 14 July 1945 with the Zugerberg cable car. Their new home, Haus Felsenegg, was in poor condition and first had to be renovated, since it had served as accommodation for soldiers during the war.

The Red Cross Children’s Relief Services and the local caregivers had differing ideas about how to spend the recovery time, i.e., how to spend the time in a sensible way, and what the traumatised young people needed most. The Red Cross representatives believed that a scout-like program would be the right thing: camping, singing songs, outdoor games, excursions, etc. In contrast, the caregivers, in addition to loving attention, focussed on teaching and learning. Materials such as textbooks, pens and notebooks were provided; classes were established and a schedule was created. Arithmetic, cultural history, geography and merchandise knowledge were among the subjects on the schedule.4

With touching words, Charlotte Weber, one of the caregivers, describes how she tried to help the young people in coping with their nightmares, their separation from their parents or even their loss: “I quietly open the door and then, I go to the bed of the boy, who has now suddenly become like a little child, lonely, abandoned. I gently caress his hair, looking for a handkerchief: ‘[...] dear child, have a good cry’, I say quietly, often I am silent just staying there. [...] So every evening I go from room to room, cover a sleeping person a little better, squeeze warm hands [...]. There is chatting, laughter, I get to hear jokes, often also very sad stories. They all call me Mummy, spontaneously and quite naturally. So now I have a hundred and seven children!”5

“gezeichnet*. The ‘Buchenwald children’ on the Zugerberg” – an exhibition

On the Zugerberg, the young people who had escaped the concentration camp were given a first opportunity to better cope with their experiences or to deal with it by talking about it. The caregivers encouraged them to do so, and many took their first steps in this direction. Those who didn’t want to or were not able to speak had the opportunity to draw, which was actively used.

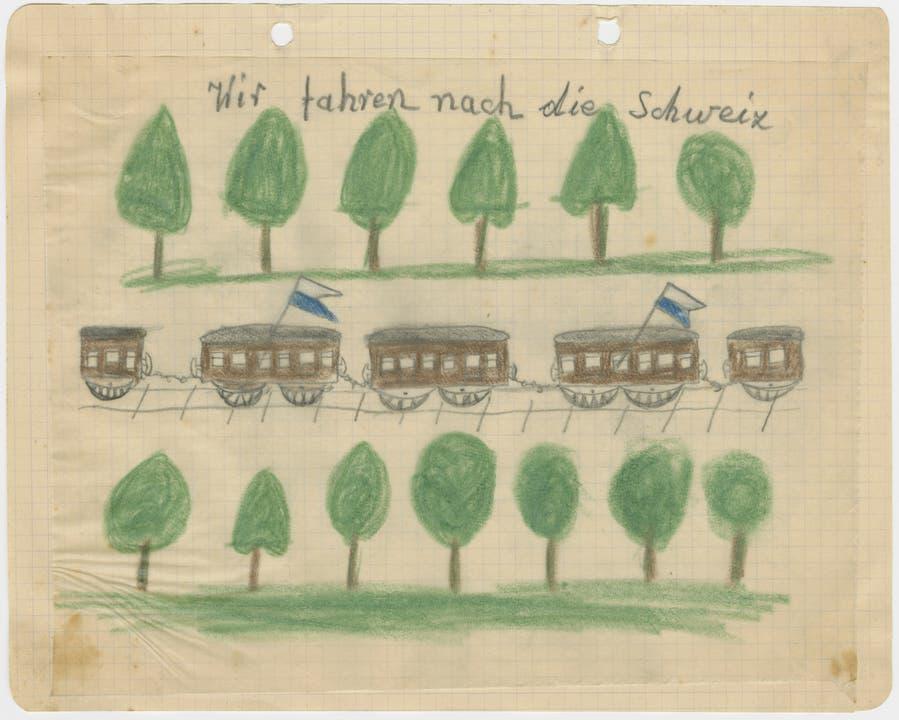

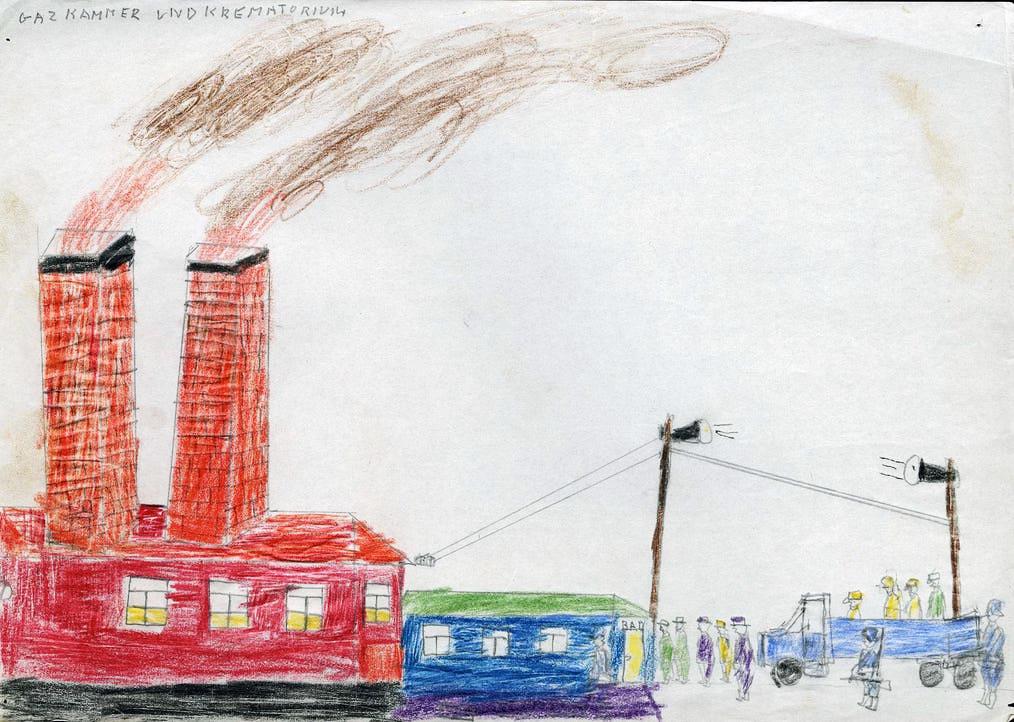

In 2018/19, the Museum Burg Zug showed 150 coloured drawings from the legacy of caregivers and private individuals, in addition to personal objects, documents, photographs, films, maps, etc.6 With impressive precision and vividness, the young illustrators clearly captured what they had experienced: their arrival in Auschwitz, physical training in the open air and hard forced labour to be performed daily, the gassing of inmates and their cremation. Torture and executions for escape attempts were also recorded in detail. Finally, the arrival of the Americans and the longed-for opening of walls and barbed wire are depicted in drawings. The graphical depiction of seventeen-year-old Kalman Landau, comprising a total of 39 illustrations, is particularly impressive: it depicts his journey from his first arrest, through his stay in the various camps, to his liberation and his journey to our country: There are green railway carriages on a track and an alley of leafy trees, and above all, the striking title: “We are going to Switzerland”.

„Outside was beautiful…“ – the example of Max Perkal

One of the young people, Max Perkal, was born in Poland in 1926. After the invasion of the German troops, he was interned in a ghetto with other thousands of Jews before being deported to Auschwitz. Via the Buchenwald concentration camp, his path leads to the Zugerberg, where he meets Charlotte Weber. In three blue school exercise books he writes down his experiences in a mixture of Yiddish (his mother tongue) and German and without a uniform spelling under the title “Schön war draussen ...” (“Outside was beautiful …”). At the end of his stay on the Zugerberg, he hands over the booklets to Charlotte Weber, who is aware that a publication is out of question for the time being: repressing the past, “crossing over to the other side by trivialising, denying”.7 — Thus she sketches from her point of view the state of mind, in which there were probably many who had escaped hell. The two met in Zurich in the early 1960s, in Jerusalem in 1970 and again in Zurich in 1994, when Charlotte Weber presented her book entitled “Gegen den Strom der Finsternis” (Against the current of darkness).8 For the first time since it was written down, Perkal picks up his notebooks again.

He agrees to the publication in the conviction that, as one of the few survivors who lost his entire family during the war, he must bear witness to the events. The text describes the period from the deportation to Auschwitz in 1943, to the stay in the Birkenau concentration camp, to the gruelling march - one of the infamous death marches – in January 1945 over the Krkonoše Mountains (Poland/Czech Republic) to the Buchenwald concentration camp near Weimar. The concise and at the same time vivid depictions of everyday life in a concentration camp contain almost all the humiliation, cruelty and sheer misery that was part of the relentless daily routine; they do not let the reader go so quickly, especially since it is always present that these are the experiences of a young person. The title “Schön war draussen draußen…” (“It was nice outside”) reflects two things: firstly, the fact that the author considers the experience of natural beauty to be refreshing, and secondly, that he is deeply moved by the fact that most people – especially the young inmates – will not be able to enjoy such experiences again and again in the future: “Look how beautiful it is outside, look how beautiful the snow shines under the sunbeams. Will we still be able to walk on this ground? Will we still get out of these wagons with our strengths, or will we be carried out in the appearance of corpses?”9

It is also the unquenchable longing for nature experiences, for the beauty of this earth, from which the author draws his will to survive: “And then in spring, when the snow is turned into water, my bones should serve as food for dogs or birds. No, I still want to live, I want to come back to my hometown unexpectedly when the war is over, and show my enemies, who think I am already dead, that I am still alive.”10 And he makes plans for the life after the war, after the camp: in his fellow prisoner Izrael Lewkowicz he has found “a brother” again, with whom he wants to take life into his own hands.11

Keeping memories alive in the service of “Never again!”

It is to the credit of Max Perkal and Charlotte Weber that they, on behalf of innumerable other refugees and refugee helpers, endeavoured to ensure that the memory of the injustice done to innumerable people in the Second World War and especially in the concentration camps is not forgotten. And they show impressively that something can be done to counter this injustice. At the Institute Montana (International School with bilingual primary and secondary school, Swiss Grammar School as well as International School with boarding school for girls and boys), where I worked for many years as a German and History teacher at the Swiss Grammar School, the memory of this part of its history is also kept alive. In 2008, Max Perkal, who now lives in the USA, had his say in a very special way on the Zugerberg: as part of an event organised by the Zuger cultural association Zuger Privileg, a reading with his notes took place in front of pupils and teachers in the Felsenegg in the assembly hall, which at the time served as a dining hall.12

To this day, the international school feels committed to the heritage of its founder Max Husmann, who, under the impression of the First World War, wanted to make a contribution to peace and under whose assistance the stay of the “Buchenwald children” on the Zugerberg was made possible: Students from many countries of the world learn and live together and demonstrate in this way that international understanding is possible and does not have to remain a utopia. •

1 The remarks on Switzerland’s relief efforts are based on the following sources: Hug, Peter. “Schweizer Spende an die Kriegsgeschädigten”, in: Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (HLS), version of 28 Ocober 2011, https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/de/articles/043513/2011-10-28/; HelveticArchives – the archive database of the Swiss National Library, Swiss Confederation, keyword: Swiss donation to war-affected persons: certificates of gratitude (1944-1948), https://www.helveticarchives.ch/detail.aspx?ID=222319

2 cf. Publications of the Archive for Contemporary History ETH Zurich, Volume 5, Chronos Verlag, Zurich 2010: Lerf, Madeleine. “Buchenwaldkinder” – a Swiss relief action. Humanitarian commitment, political calculation and individual experience, https://www.afz.ethz.ch/publikationen/schriftenreihe/buchenwaldkinder

3 vgl. Schmutz, Barbara. «Was man erlebt hat, bleibt im Kopf drin», (What you have experienced stays in your head), in: Zuger Neujahrsblatt 2008, published by the Charitable Society of canton Zug, Zug 2008, p. 73, http://www.zugerneujahrsblatt.ch/_uploads/Archiv_ZNJB/Zuger_Neujahrsblatt_2008.pdf

4 cf. ibid. p. 77

5 ibid.

6 cf. the contribution of: Swiss Cultural Television on the Net: Museum Burg Zug, Drawn* Holocaust, published on 16 January 2019, https://www.arttv.ch/mehr/museum-burg-zug-gezeichneter-holocaust *means both "drawn" and "ravaged"

7 Weber, Charlotte. “The notebooks of Max Perkal”, in: Max Perkal; Charlotte Weber; Aron Ronald Bodenheimer: Outside was beautiful: the notebooks of a 19-year-old Jew written in 1945. Published by Chronos Verlag and The Menard Press, Zurich, Switzerland and London (1995), p. 66

8 Weber, Charlotte. “Gegen den Strom der Finsternis. Als Betreuerin in Schweizer Flüchtlingsheimen 1942–1945” (Against the current of darkness. As a caregiver in Swiss refugee homes 1942-1945), Zurich 1994 (Chronos Verlag)

9 Max Perkal; Charlotte Weber; Aron Ronald Bodenheimer: “Outside was beautiful: the notebooks of a 19-year-old Jew written in 1945”. Published by Chronos Verlag and The Menard Press, Zurich, Switzerland and London (1995), p. 51, spelling and vocabulary of the original

10 ibid. p. 50

11 ibid. p. 39

12 cf. Pogorzelski, Winfried. “Aus der Hölle Buchenwald auf den Zugerberg. Lesung aus den Aufzeichnungen des 19jährigen Juden Max Perkal in der Aula” (From the hell Buchenwald to the Zugerberg, reading from the notes of the 19-year-old Jew Max Perkal in the assembly hall), in: Montana Blatt No. 179, Zugerberg 2008, p. 8

(Picture Archive for Contemporary History ETH Zurich: NL Charlotte Weber/85)

(Picture Archive for Contemporary History ETH Zurich: S Biographies

and Special Topics/78)