“To learn to use the force of our humanity”

Another look at 30 years of “reunification”

by Karl-Jürgen Müller

3 October 2020 marked the thirtieth anniversary of the accession of the previously newly founded five states of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) to the area of application of the Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany. From then on, the Basic Law, which was adopted in 1949 only as a transitional text, also applied to the people of the former German Democratic Republic with only minor changes. The wish of a number of East German civil rights activists for a new all-German constitution, which had been jointly drafted and decided by referendum, was not granted. It is commonly referred to as “reunification”, but the term is misleading. People in the former GDR were obliged to adapt to previous Federal Republican conditions and customs in almost all areas of life. The „reunification“ was dominated by the Federal Republic.

30 years is an occasion to think about many things. The judgments on 3 October 1990 and the following 30 years are very different. No detailed own judgement should be added here. It should merely be pointed out that despite (or perhaps because of) the pressure to adapt, there are still different ways of thinking and patterns of behaviour in the west and east of Germany. This is already evident from the fact that the election results in East and West favour completely different political parties. Anyone who comes to East Germany and enters into an open discussion quickly realises that many things are judged differently in the East than in the West. Less helpful are the voices that link these differences with a negative judgement of the East Germans. So, there will be no convergence in the future either. It would be better to take the voices and the mood in East Germany seriously and seek honest dialogue. But the current political environment is not very helpful in this respect.

No hope for a short-term political turnaround

Many are therefore hoping for the success of mass citizen protests. But the loud cry “We are the people” is no guarantee for a truly democratically legitimised, honest direct-democratic turnaround. The term “critical mass” used by protagonists of such movements illustrates the problem. They keep saying that a mass movement for political objectives does not need a majority of citizens behind it, and that there will be a majority some day, if the “critical mass” is only loud and determined enough. To what extent are citizens here considered to be mature?

It is also time to admit that the contribution of “peaceful revolutions” to the changes in the former Warsaw Pact states was probably not the decisive factor. Just as the subsequent colour revolutions were in many ways externally driven.

An honest political turnaround, in which not only the old rulers are replaced by new ones, must follow a serious direct-democratic path. This presupposes a lot: a good national education; respect for the dignity of all people, including those whose policies you would like to change; the courage to take many small steps; the willingness to undertake unspectacular development work; mature personalities with an honest democratic basic convictions; and above all: a staying power that thinks beyond a generation. Anyone who does not consider how diverse the ways are to prevent real democracy is building on sandy ground.

Political regresses in Germany since 1990

The enlarged Germany has taken considerable steps backwards since 1990. It is not the place to list all the points here. This is most conspicuous and worrying in the “new” foreign policy and military orientation.

The representatives of the four victorious powers of the Second World War, together with the representatives of the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic, had agreed in the “Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany”, or “Two Plus Four Agreement” for short, signed on 12 September 1990, as the basis for the “new” Germany with Article 2:

“The Governments of the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic reaffirm their declarations that only peace will emanate from German soil. According to the constitution of the united Germany, acts tending to untertaken with the intent to disturb the peaceful relations between nations, especially to prepare for aggressive war, are unconstitutional and punishable offence. The Governments of the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic declare that the united Germany will never employ any of its weapons except in accordance with its constitution and the Charter of the United Nations”.

Since the beginning of the 1990s, German politicians have been shaking this to the core with their “salami tactics” for the gradual realisation of German Armed Forces missions abroad. Less than ten years later, in 1999 during NATO’s war of aggression against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, the then German government clearly broke that treaty – and the German parliament and the German courts did not contradict.

Ursula von der Leyen is fuelling the „bogeyman Russia“.

So where are we today? Here is just one example of unfortunately very many. Ursula von der Leyen, former German Defense Minister and current President of the EU Commission, emphasised right at the beginning of her “State of the [European] Union Address“ on 16 September 2020:

“To those that advocate closer ties with Russia, I say that the poisoning of Alexei Navalny with an advanced chemical agent is not a one off. We have seen the pattern in Georgia and Ukraine, Syria and Salisbury – and in election meddling around the world. This pattern is not changing – and no pipeline will change that.”

Not “only peace will come” from such flat bogeyman constructions.

The political conditions in Germany today are not very pleasant, even for those who reject simple black and white drawings. They will not be changed for the better from one day to the next, as I said before.

Overcoming walls and building bridges with humanity

Must citizens therefore be politically passive? The answer is no. We have already pointed out the long-term tasks that lie ahead. There is something else that is widely underestimated in terms of its importance for change in politics: concrete acts of humanity and international understanding. These are always possible, even under the most difficult conditions. Humanity and international understanding follow the social nature of man, it can overcome walls, build bridges and bring conflicting parties closer together, immunise against enemy images and are the ferment of togetherness.

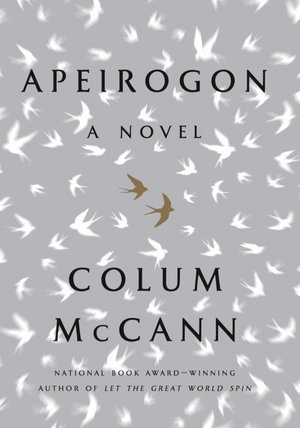

In Current Concerns No. 18 of 31 August 2020, there was already talk of a newly published non-fiction novel. The award-winning Irish author Colum McCann, who lives in New York, also published it in German in August 2020 with the title “Apeirogon”. The main characters are an Israeli and a Palestinian. Both, the Israeli and the Palestinian, have lost their 14- and 10-year-old daughters in an act of violence: the Israeli through Palestinian suicide bombers, the Palestinian during an Israeli police operation in the West Bank. But both fathers have not given in to hatred and revenge. They work together in the joint Israeli-Palestinian peace movement. The two main characters in this novel, Bassam Aramin and Rami Elhanan, are real people. The death of their two daughters Abir Aramin and Smadar Elhanan is also a bitter reality.

The novel is divided into 1001 chapters. Counting starts from 1 to 500, then there is a chapter headlined 1001, and then counts backwards, from 500 to 1 at the end of the novel. One of the most impressive parts of the novel are the two chapters 500, where Bassam Aramin and Rami Elhanan themselves have their say. Both show humanity and international understanding in a situation that most of us can hardly imagine. But let one of the two, the Israeli Rami Elhanan, speak for himself.

The story of Rami Elhanan

“My name is Rami Elhanan. I am the father of Smadar. […] I was a young soldier fighting the October ‘73 war in Sinai, a horrible war, everyone knows this, it’s no revelation. […] My job included bringing in ammunition and taking out the dead and wounded. I lost some of my very close friends, carried them out on stretchers. I emerged from the war bitter, angry, disappointed, with just one thing on my mind – to detach myself from any kind of involvement or commitment, to block myself off from anything official at all.”

A few pages later, Rami Elhanan describes the death of his 14-year-old daughter, his thoughts and feelings in the days and weeks that followed:

“You have to make a decision. What are you going to do now, with this new, unbearable burden on your shoulders? What are you going to do with this incredible danger that eats you alive? […] the first choice is obvious: revenge. When someone kills your daughter you want to get even. You want to go out and kill an Arab, any Arab, all Arabs, and then you want to try to kill his family and anyone else around him, it’s expected, it’s demanded. Every Arab you see, you want him dead. […] Look, I have a bad temper. I know it. I have an ability to blow up. Long ago, I killed people in the war. Distantly, like in a video game. I held a gun. I drove tanks. I fought in three wars. I survived. And the truth is, the awful truth, the Arabs were just a thing to me, remote and abstract and meaningless. I didn’t see them as anything real or tangible. They weren’t even visible. […] Then after a while you start asking yourself questions, you know, we’re not animals, we can use our brains, we use our imaginations, we have to find a way to get out of bed in the morning. And you ask yourself, Will killing anyone bring my daughter back? Will killing every other Arab bring her back? Will causing pain to someone else ease the unbearable pain that you are suffering?”

Israelis and Palestinians, who “nevertheless wanted peace”

Through an orthodox Jew, Jitzschak Frankenthal, whom he first meets with many prejudices, he gets to know a circle of parents, Jews, Palestinians and other affected people who have lost one or more children in the violent clashes that have been going on for decades, a circle called the “Parents Circle”, people who “nevertheless wanted peace”.

The first time he also meets a Palestinian woman:

“I was standing there, and I saw a few Palestinians passing by in a bus. Listen, this flabbergasted me. I knew it was going to happen, but still I had to do a double take. Arabs? Really? Going into the same meeting as these Israelis? How could that be? A thinking, feeling, breathing Palestinian? And I remember seeing this lady in this black, traditional palestinian dress, with her headscarf – you know, the sort of woman who I might have thought could be the mother of one of the bombers who took my child. She was slow and elegant, stepping down from the bus, walking in my direction. And then I saw it, she had a picture of her daughter to her chest. She walked past me. I could’t move. And this was like an earthquake inside me: this woman had lost her child. It maybe sounds simple, but it was not. I had been in a sort of coffin. This lifted the lid from my eyes. My grief and her grief, the same grief. […]

You see, I was forty-seven, forty-eight years old at that time, and I had to learn to admit it was the first time in my life, to that point – I can say this now, I could never even think it then – it was the first time that I’d met Palestinans as human beings. Not just workers in the streets, not just carricatures in the newspapers, not just transparencies, terrorists, objects, but – how do I say this? – human beings – human beings, I can’t believe I’m saying that, it sounds so wrong, but it was a revelation – yes, human beings who carry the same burden that I carry, people who suffer exactly as I suffer. An equality of pain.”

The duty to understand, what is going on around us…

“Some people have an interest in keeping the silence. Others have an interest in showing hatred based on fear. Fear makes money, and it makes laws, and it takes land, and it builds settlements, and fear likes to keep everyone silent. And, let’s face it, in Israel we’re very good at fear, it occupies us. Our politicians like to scare us. We like to scare each other. We use the word ‚security’ to silence others. But it’s not about that, it’s about occupying somone else’s life, someone else’s land, someone else’s head. It’s about control. Which is power. And I realised this with the force of an ax, that it’s true, this notion of speaking truth against power. Power already knows the truth. It tries to hide it. So you have to speak out against power. And I began, back then, to understand the duty we have to try to understand what’s going on. Once you know what’s going on then you begin to think: What can we do about it?”

…and to keep on putting tiny cracks in the wall

By quoting only a few excerpts from a novel, you cannot do justice to the whole work. The words of Rami Elhanan deserve to be read completely. In the following pages he describes what he has decided to do. His answer to the question: “What can you do yourself?” He criticises the occupation policy as inhumane. But he sees his main task in telling his very personal story, in devoting his life to,

“going everywhere possible, to talk to anyone possible […]. My name is Rami Elhanan, I am the father of Smadar. I repeat it every day, and every day it becomes something new because somebody else hears it. I will tell it until the day I die, and it will never change, but it will keep on putting a tiny crack in the wall until the day I die.”

No less impressively tells the Palestinian Bassam Aramin. One of his statements is:

“We had to learn to use the force of our humanity.”

Palestine, Israel … and Germany

It will be said that the situation in the Middle East is very different from that in Germany and Europe. On the one hand, this is true, but on the other hand the following must be pointed out:

The examples of the Palestinian Bassam Aramin and the Israeli Rami Elhanan show that even in a region of the world where violence, the principle of revenge and mutual hatred are part of everyday life, understanding and humanity are possible – if people choose to do so. How much easier it must be in a country like Germany or in the relations between the peoples of Europe – if here too the will to do so is strong enough.

The dynamics should not be underestimated of the sometimes sharp polarisation of public and private conflicts, the enemy stereotypes within Germany – for example, “left” against “right” – or else within Europe – for example, EU states against Russia and its allies. If unabated, violence can also result from this – with all its consequences.

So far there is no evidence that the German state is taking appropriate steps to counteract these developments. All the more reason for the citizens to take action. •