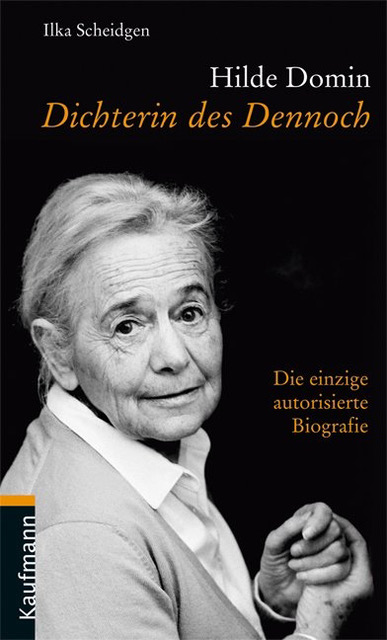

Hilde Domin – Poetess of the Nevertheless

On the book by Ilka Scheidgen about a great humanist

by Susanne Wiesinger

The poet Hilde Domin, born in 1909, grew up in Cologne as Hilde Löwenstein, daughter of her Jewish parents Löwenstein. Her father was a lawyer and her mother a singer. Her mother performed her artistic activities only once in public. She devoted herself, as was customary at the time, as a woman to the upbringing of her two children and the household. Hilde had a younger brother and the relationship between the siblings is described as harmonious.

Atmosphere in the parental home reason for her basic trust

Hilde Löwenstein later described the atmosphere in her parents’ house as the reason for her basic trust, her confidence in people and her good and optimistic view of humanity. These qualities distinguished her from many other exiled poets, most of whom never returned to Germany.

In retrospect, Hilde Domin praised the fact that as a child she “(was allowed) to even tell the truth” and that her father told her about his court cases on long walks and seriously listened to her opinions. He took her to the theatre, to swimming and museums and discussed her school essays with her.

Hilde attended the Humanistic Girls’ High School Merlo-Mevissen in the old town of Cologne. She could study and choose her own subjects and even switch from law to economics, sociology and philosophy. There were many subjects of which at the time the young student expected to change the world, as Ilka Scheidgen, the biographer of Hilde Domin writes (Scheidgen, p. 20).

Exile in the Dominican Republic

As a social democrat with political sensitivity, she suspected that the Nazis would gain power in Germany. In her environment, this earned her the nickname “Cassandra”. In 1932 she went into exile in Italy with her friend and later husband, the archaeology student Erwin Walter Palm, and from there to England. In 1940, they escaped internment there on the grounds of their German citizenship by undertaking a six-week risky sea voyage to the Dominican Republic in order to go into exile. No money or engineering diploma was required for entry there.

They arrived at a “wooden landing stage which led into the middle of a sugar field”. “Here we were in a sugar field, where the sugar canes were bigger than we.” (Scheidgen, p. 59) Nobody was expecting them. With a vehicle they arrived in the capital and built up a common life as intellectuals. Erwin W. Palm as professor for the history of architecture in the Dominican Republic, Hilde as his advisor, translator and copywriter. Besides she earned some money for her living as a language teacher (Scheidgen, pp. 62).

Continuing interest in everything new in the unknown land

It is impressive to see the great curiosity and continuing interest with which they encountered the new in the unknown country and how they soon gathered a circle of friends, exiled Spaniards, South Americans and artists from other countries. They got used to the fact that sometimes a snake stuck its head out of the bookshelf or termites eroded the books (Scheidgen, p. 68).

Hilde Palm vigorously supported her husband’s professorship for a long time and put her own plans on hold. In 1954, Hilde Domin was shaken by the unexpected death of her mother – as a result of a shock caused by the German authorities upon withdrawal of the American passport. This loss of “My July leaves/My wind shelter/My mother” hit Hilde Domin so hard that she fell into a major life crisis. By resorting to poetry and making reality liveable again through poetry, she escaped the psychic abyss that lay ahead of her and literally returned to life. Her self-discovery as a woman had to lead to arguments with her husband. When she showed him her first poem, he slammed the apartment door and she said to herself that it probably was a successful poem (Scheidgen, p. 78).

Life as a poet, criticism of the Frankfurt School

Ilka Scheidgen’s “only authorised biography” entitled “Hilde Domin, poetess of the Nevertheless” vividly and comprehensibly describes the poet’s life, her exile and her return to Germany in 1955 and knowledgeably discusses her theoretical approaches, poetry and writing practice. The prose writings were written in the course of her confrontation with Adorno, Marcuse and Marxists such as Lukacs and others. In her poetics lectures at the university in Frankfurt (!), she contrasted the 68generation’s claim of the “death of literature” and the “reactionary of poetry”, that was despised, with her conviction of the power of poetry (Scheidgen, p. 202, p. 186). As a result of her upbringing and her attitude to life, her aim was “to strengthen the courage to live: to set a nevertheless against the fatal ‘no-future’ panic” (Scheid-gen, S. 202).

To strengthen courage to face live, defence of human dignity

“In the very first reading Hilde Domin presented her belief in a positive and saving function of the poem, in as much as she had written the programmatic verses

'This is our freedom

calling the proper names

fearless

with the little voice’

as a starting point for further reflection.” (Scheidgen, p. 202/203)

Her main concern as a Jewess who experienced in an exemplary way how a human being becomes a victim from one moment to the other “condemned to helplessness” (Scheidgen, p. 167), was the defence of human dignity, “the undeletable without which life is meaningless” (Domin, quotes after Scheidgen, p. 167).

In connection with the student revolts in the 1968s and their “rehabilitation of intolerance” Hilde Domin lamented that “with the suspicion of tolerance and trust, language became suspicious, too, right down to the grammar.

It was declared a means of deception, of overreaching, in short, the ‘language of the ruling class’. The discussions, the demand of the hour, were hateful and degenerated into terror of opinion. Criticism slipped into a ghostly crusaderism, which was completely in the abstract. Voluntarily and without coercion from above, the intellectuals created for themselves a quasi-totalitarian climate. (Domin, quoted after Scheidgen, p. 171)

Commitment to peace and criticism of nuclear armament

In response to the pressing question of war or peace in a Germany armed with nuclear weapons in the 1970s and 1980s, Hilde Domin wrote the poem “Abel aufstehen” (Abel arise), which she considers her most important poem. In this poem with a utopian character, the poetess makes it possible for Cain to get a second chance, “where he can say Yes, I am here, I, your brother”. It is a plea for brotherly and sisterly humanity (Scheidgen, p. 164).

Abel arise

Abel arise

it must be played again

daily it must be played again

daily the answer must lie ahead

the answer yes must be made possible

if you don’t arise Abel

how shall the answer

the only significant answer

how shall it ever change

we can close all churches

abolish all law books

in all the languages of the globe

if only you rise

at make it unspoken

the first false answer

to the only question

that counts

arise

so that Cain says

so that he may say

I am your keeper

Brother

how could I not be your keeper

[…]

(Translation: Agnes Stein)

True naming and love

According to Scheidgen, there are “two main commandments for Hilde Domin: the true naming and love, love as a reversal of Cain’s words: ‘Am I my brother’s keeper?’” (Scheidgen, p. 164) With the first main commandment she opposes the wrong naming, for example “protective custody” for prison or “special treatment” for murder, and refers to the Chinese philosopher Confucius: “If the language is not right, what is said is not what is meant, the works do not come into being; if the works do not come into being, justice does not come into being; if justice does not come into being, the people do not know where to put their hands and feet. Therefore, one must not tolerate arbitrariness in words. That is all that matters. (Confucius, quoted after Scheidgen, p. 151)”

Poems, good for school lessons

Since Hilde Domin’s poems are easy to understand, they are well suited as a basis for interpretation in German lessons. In all types of schools, from high school to elementary school, students find pleasure in recasting poems like the following:

“Abel fight

Abel, fight for your brother

and defeat his violence

go against his envy

erase the mark on his forehead.

Abel, get up!

erase the mark on our foreheads.”

(Florian Kruse, quoted after Scheidgen, p. 196)

Hilde Domin many a time read at schools in front of her grandchild generation and found enthusiastic readers of all ages.

When Marcel Reich-Ranicki undertook to bring the poem back to life by means of a forum in the “Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung” (Frankfurt Anthology), as adversary to the 68generation who disdained the poem and defamed it as “reactionary”, Hilde Domin made poems available for the column in the “Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung” since 1974.

Hilde Domin is characterised by her “tremendous courage to face life”, her basic trust. In the course of publishing her poems, she acquired her artist’s name as a reminiscence of the Dominican Republic, that took her in for 12 years. The primal trust was based on the experience of a generous, non-coercive parental home and on the experience that a new beginning in Germany was possible (Scheidgen, p. 194).

This courage to face life appeals to the readers and especially to young readers; in addition, the always up-to-date content of the poems which were written during confrontation with their own time. Hilde Domin’s claim was to realise that life and work of a poet do not contradict each other and in this she succeeded.

Do not grow weary

Do not grow weary

but gently

to the wonder

as if a bird should light

hold out your hand.

Hilde Domin

(Translation Current Concerns)