Dual vocational education as an essential component of the Swiss model

On the book “Vocational education. Development of the Swiss system” by Emil Wettstein

by Dr iur. Marianne Wüthrich

In the year just ended, there were also in Switzerland young people who complained about the “restriction” of their freedom because discos and bars were temporarily closed and neither open airs nor football matches open to the public took place. In reality, Swiss youth are privileged like perhaps no one else in the world. How happy many young people in other countries would be if they were allowed to do an apprenticeship and contribute to the alimentation of their families with their apprenticeship wages! (Most Swiss apprentices have the major part of their wages as pocket money).

In 2020, Emil Wettstein, for many years head of the ABB technical school and later head of the higher education unit for vocational school teachers at the University of Zurich, presents in an easy-to-understand way in a new version of his work published over thirty years ago, how vocational education and training has developed in the history of Switzerland.1 “How was Switzerland able to develop a dual vocational education model? Why are Swiss entrepreneurs willing to make such a strong commitment to vocational education for young people?” Such questions are asked by interested people from other countries who want to learn about the Swiss system. According to the editor of the book in his foreword, these questions can only be answered by looking back into Swiss history. It should be added that the history of Swiss vocational education is interwoven with the development of democracy; the way vocational education is implemented here is part of the Swiss model. This does not mean that good vocational education cannot be introduced in other countries. However, it is advisable to spend time and care in its constitution.

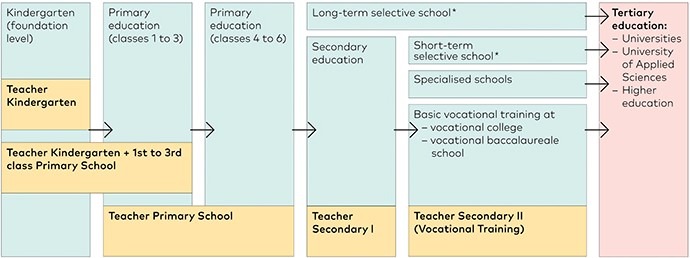

The apprenticeship is very popular among young people in Switzerland. Two-thirds of school leavers opt for an apprenticeship, and in some German-speaking cantons the figure is over 80 percent. Basic vocational education is completed after three or four years with a Federal Vocational Education and Training Diploma (Eidgenössisches Fähigkeitszeugnis, EFZ) or after two years with a Federal Vocational Certificate (Eidgenössisches Berufsattest, EBA). If the young professionals want to continue their education, there are a number of options after the apprenticeship. However, many of them want to stay with their profession and, thanks to their professional and human qualities, often become the top executives who give Switzerland its good reputation as a business location.

Almost every Swiss enterprise is an apprenticing enterprise

What is special about dual vocational education is the little word “dual”. Education takes place in two places: in the apprenticing company (usually three days a week) and in a vocational school (usually a state school, two days a week). There is the possibility to do an apprenticeship for almost every occupation; about 230 occupations are available. Almost all SMEs, but also all large private and state-owned companies in Switzerland educate and train apprentices, as do the administrations of the municipalities, cantons and the federal government. Over fifty professions can be learned at the federal government alone! (https://www.stelle.admin.ch/stelle/de/home/einstiegsmoeglichkeiten/schueler.html)

Even in the Corona year 2020, almost everyone who wanted to start an apprenticeship in August found a job because the entrepreneurs did everything humanly possible to offer enough apprenticeships.

The fact that it is a matter of course for Swiss entrepreneurs today to introduce young people to working life, to share their professional knowledge and to show them the way to become capable, social and reliable adults does not come automatically. It is based on a long tradition and is also rooted in the Swiss militia model. Every young person is of importance to the whole by taking his or her place in professional life and as a citizen in the community, participating in his or her environment and exercising his or her political rights responsibly. For its part, the apprenticing company has in the educated apprentices reliable professionals who know how the business runs and who are well integrated into the team.

The beginnings of vocational education in the guilds

The book “Vocational Education” by Emil Wettstein begins with the historical roots of vocational apprenticeship in the guild system. Where a differentiated vocational education system later developed in Europe, crafts had often been organised in guilds since the Middle Ages (in Switzerland, mainly in German-speaking cities, but also, for example, among watchmakers in the French-speaking Jura). The guilds were professional associations and at the same time social communities, which in particular regulated and ensured the education of the next generation. At that time, the entire education took place under the guidance of a master, who passed on his craftsmanship and professional knowledge, but also the social skills that were consolidated while living together in the household of the master and his family and later enabled participation in urban society as a professional and citizen (Wettstein, pp. 57–59).

The guilds did not survive the 19th century – i. e. the legal equality of the population in town and country introduced with the Helvetic system, the freedom of trade and commerce and the emerging industrialization. Nevertheless, the guild system laid the foundations for good vocational education, which could be taken up again in the 19th and 20th century in a contemporary form.

Good school basics as a prerequisite for vocational education and Swiss quality products

In the 19th century, many craftsmen struggled for their existence. In addition to the industrial production of textiles and other goods, increasing competition from abroad made life difficult for them. In order to keep up, trade and industry in resource-poor and landlocked Switzerland, relied on the high quality of their products from an early stage. Then, as now, this required vocational education that could build on solid basics in at least reading, writing and arithmetic. The prerequisite for this is a good Volksschule2. From the 1830s onwards, the cantons introduced the compulsory primary school, which was not only intended to enable pupils to learn a profession. The school law of the canton of Zurich of 1832 e. g. stated that the purpose of the school was “to educate the children of all classes of people according to consistent principles to become intellectually active, civically suitable and morally religious people.” (Wettstein, p. 60).

As early as the first half of the 19th century it was realised that after the mostly six-year primary schools, further educational opportunities were needed in addition to the grammar schools. For this reason, many cantons established advanced training or “repetition schools”, in some cases also craft or drawing schools, which were attended outside working hours in the evening or at weekends (Wettstein, p. 62).

Even after the founding of the federal state in 1848, the school system remained in the hands of the cantons (in principle until today). The revised Federal Constitution of 1874 stipulated in Article 27 that the cantons had to ensure “sufficient primary education” in compulsory and free state schools. Implementation was left to the cantons, and vocational education also continued to be regulated by the cantons. The Confederation has been promoting commercial, industrial and agricultural vocational education with subsidies since 1884. At the turn of the century, most cantons enacted laws on apprenticeship, and some stipulated the attendance at the vocational school and taking a final apprenticeship examination. (Wettstein, pp. 65–69).

Professional education and training as a joint effort of the Confederation, cantons, training companies and professional associations

The first Federal Vocational and Professional Education and Training Act (VPETA) was passed by the Federal Assembly in 1930 after lengthy preparatory work and consultations with the cantons and employee and employer associations, and came into force on 1 June 1933. It applied to the commercial, industrial and trade professions.

In addition to the commercial professions, other professions had developed separately: the agricultural apprenticeship (Wettstein, pp. 103ff.); the commercial apprenticeship – the “KV”: the schools still belong to the commercial associations KV in many cantons, but are financed by the cantons (pp. 94ff. ); the non-medical health professions – the nurses’ schools were for a long time run by Catholic or Reformed organizations, in 1899 the Swiss Red Cross founded the first Red Cross nurses’ school, later the Confederation delegated the enforcement of legislation in this field to the SRC (pp. 118ff.).

The BBG of 1933 took up the vocational training model of the guilds. As early as 1895, the Swiss Trades Association (SGV) had decided not to go down the path of apprenticeship workshops with associated specialised instruction, but to stick to the master apprenticeship. This was an important and appropriate decision for the further development of vocational education and training - after all, it is human nature that young people can learn and grow best in a direct relationship with an older, experienced professional or master teacher - this is just as true in the enterprise as it is at school.

The 1933 law already contained the most important elements of today’s vocational training. It regulated the basic training in a vocational apprenticeship (enterprise and trade school) with final apprenticeship examination and certificate of proficiency, but also the training of master teacher. The technical schools and apprenticeship workshops, which were especially widespread in French-speaking Switzerland, were included. The apprenticeship contract was and is regulated as a special form of employment contract in the Code of Obligations (OR).

“The basis for the subsequent success of the law,” writes Emil Wettstein, “is the involvement of the cantons and professional associations in the design of the regulations, their further development and their enforcement” (Wettstein, p. 70). Among other things, the professional associations help determine the content of the training regulations in the individual professions and administer the practical final apprenticeship examinations. The cantons are responsible for the implementation of the BBG, they run the vocational schools and supervise the training enterprises. Legislation is the responsibility of the Confederation.

Some things have been adapted and further developed in subsequent decades to reflect changes in the world of work. But the basic principles and the cooperation model remained, because they proved to be practical.

Permeability of the Swiss vocational education and training model – from apprenticeship to university

The new education articles, which the sovereign inserted into the Federal Constitution in 2006, did not lead to better schooling for all – as many had hoped – but were used as a springboard for questionable upheavals (HarmoS, Lehrplan 21). As far as vocational education is concerned, the Confederation retained the competence to legislate and newly stipulated: “It [the Confederation] shall promote a broad and permeable offer in the field of vocational education and training” (Art. 63 BV).

This permeable offer looks briefly like this: Since 1994, there has been the vocational baccalaureate for those apprentices who like to put in more learning time - whether at the same time as their apprenticeship or afterwards. In 2019, around 68,000 young people completed a vocational apprenticeship, and over 14,000 acquired a vocational baccalaureate (BM).3 With a BM for commercial, technical, health/social, creative/artistic, agricultural or service professions, the path to the corresponding university of applied sciences is open. Since 2005, people with a vocational baccalaureate have also been able to enter university or the ETH via a one-year additional training course with a supplementary examination (the so-called Passerelle). Just under 1200 passed the Passerelle in 2018 (Wettstein, p. 168ff.).

As Emil Wettstein notes, the introduction of the vocational baccalaureate “has made a significant contribution to increasing the attractiveness of the vocational pathway” (Wettstein, p. 172). Some high-achieving students would rather do an apprenticeship than go to high school if they can combine it with a BM. But, as education editor Robin Schwarzenbach writes in the “Neue Zürcher Zeitung”: “Those who want, can – but no one has to strive for further diplomas. Young people in particular don’t have to – indeed, they can’t – know today where they will be in their professional lives in five or ten years’ time. They should be allowed to take one step at a time. At their own pace, according to their own inclinations and interests.”4

Matura for all – is that fairer?

Sometimes we hear that a fair education system should make it possible for all young people to take the Matura. This demand aims past reality. On the one hand, many bright young people would rather do an apprenticeship than spend the whole week at school. On the other hand, such “fairness thinking” in no way does justice to the inestimable advantages of Switzerland’s dual VET system: for the lives of individual young people (and this does not just mean their professional future!), for the high quality of the workplace, for the extraordinarily low youth unemployment (2–4 %) and for a vibrant democracy.

The education reform of 2006 stipulates: The Confederation and the cantons “shall, in the performance of their tasks, endeavour to ensure that general and vocational education and training receive equal recognition in society” (Art. 61a para.3 BV).

However, this “equal recognition” is not achieved by packing vocational apprenticeships together with secondary schools into the new box “upper secondary level”. Rather, it must take place in our minds.

One of my first profound experiences as a vocational school teacher were the essays that my electrician, machine mechanic and mechapraktiker classes (today the professions are called differently) wrote after the first months of their apprenticeship on the topic “From school to working life”. The way the 15- and 16-year-olds vividly described the enormous change from the cosy life of a high school student to a strict and fully committed working day, and how they coped with it within a few months, how they (almost without exception) expressed their joy in their profession, in creating independently, their pride in the first workpieces they produced themselves and, of course, also in their first payday, shook the rest of my academic pride to the core. What a unique opportunity the dual vocational apprenticeship offers most of our young people to mature and take their place in life in the important phase between 15 and 20!

This is by no means to say that the “Gymi” cannot also be a good choice. I, at least , have (mostly) enjoyed the intensive learning in the classroom and at home. It is equally clear that it is one of the tasks of us vocational school teachers to do our utmost to support every young person who would like to pursue further education after the apprenticeship, perhaps the vocational baccalaureate and a degree.

Optimal adaptability of the apprenticeship to the requirements of the time – exception ABU

Much has changed in the world of work since the first Federal Vocational and Professional Education and Training Act of 1933. Swiss VET has managed to adapt to this change: Occupations have been renamed or newly created, occupational regulations and school-based learning content have been revised. “This is by no means a matter of course,” says Emil Wettstein. “In many countries, education has become disconnected from the needs of the world of work, leading to labour market mismatches and thus youth unemployment” (Wettstein, p. 216).

The secret of the adaptability of Swiss vocational education and training is quite simple: Because vocational education and training comes from practice and because the professional associations and the training companies bring the requirements of reality to the cantonal and federal offices, because the vocational schools maintain contact with the apprenticeship masters, and because the specialist teachers themselves usually learned the profession the apprentices of which they teach today – for all these reasons, the learning theories and the subject teaching in the vocational school do not drift away from everyday vocational life.

Unfortunately, the exception to this reality-based approach is the general education teaching (ABU). When I started as a vocational school teacher in the 1980s, we had our three weekly lessons for the subjects German, business studies and political and economic studies. There was one curriculum for the entire German-speaking Switzerland with uniform learning objectives and a uniform apprenticeship-leave exam (LAP) with a demanding level, in all German-speaking Swiss vocational schools on the same day at the same time.

In the nineties, school reformers used the ABU as an experimental field for their ideologies which we are also grappling with today in Volkschule: The school subjects were abolished and replaced by a mishmash called “general education”. The learning objectives were “enriched” with “action, factual, self and social competences”, there was only one framework curriculum, each school fabricated its own school curriculum and its own LAP according to the motto: “He who teaches, tests.” This led to a massive reduction in the learning material and the examination level. In addition, a lot of common learning time is lost in general education classes for the “Vertiefungsarbeit (VA)”, which every student has to write and present “self-organised” as part of the final examination. Fortunately, the reformers’ ideas were thoroughly rebuffed by the specialist teachers and industry associations.

Caring for the business location

Emil Wettstein’s history of Swiss vocational education and training shows the great importance of dual vocational education and training as one of the pillars of the economy and the cohesion of society.

In any case, we don’t need to worry about the Swiss economy just because of a little thunder from Brussels. Against such behaviour, our clever people in the Federal Council and in the administration pull out of their pockets their plan B. Our entrepreneurs are flexible and innovative anyway. But if our companies want to continue to deliver top quality, they do need top skilled workers. For quite some time now, many apprenticeship masters have been complaining that their apprentices bring along from the Volksschule sufficient school basics. Also, they often lack the willingness to work hard as well as a frustration tolerance. We have to do something about this – better today than tomorrow. •

1 Wettstein, Emil. Berufsbildung. Entwicklung des Schweizer Systems. (Vocational education. Development of the Swiss system). © 2020 hep Verlag Bern. ISBN 978-3-0355-1675-3

2 Volksschule is equivalent to a combined primary and lower secondary education.

3 Swiss Federal Statistical Office, Bildungsabschlüsse Berufliche Grundbildung/Allgemeinbildende Ausbildungen (Educational attainment in basic vocational education and training/general education and training).

4 Schwarzenbach, Robin. “An apprenticeship is just the beginning”. in: Neue Zürcher Zeitung. Education supplement from 25 November 2020

Vocational Education: A step-stone to the working world

Projects of the Directorate for Development and Cooperation (SDC)

mw. The employees of SDC report on the Swiss experience with the dual vocational education and training in many projects around the world.

“High quality vocational education and training can make a decisive contribution in reducing poverty if it enables those who are learning with long-term and dignified working conditions and as such they can get a foothold into the labour market. Economic growth remains in the foreground for the benefit of all. In cooperation with the authorities and the private sector, SDC developed training courses which meet the needs of the labour market.”

Testimonials

- from Bolivia: Doña Silvia, baker: "I was saved when the community installed its first oven and we were invited for training."

- from Rwanda: Mediatrice Nyirahabimana, hairdresser: "One month after the training, I am able to provide my basic needs. I believe in a very good future."

- from Burkina Faso: Kader Kouanda, tailor: "Now I know how to read, take my clients' measurements and talk to them. I'm pleased with the evening classes."

and many more …