We want to spend a lifetime solving the riddle of the human being, because we want to be human.

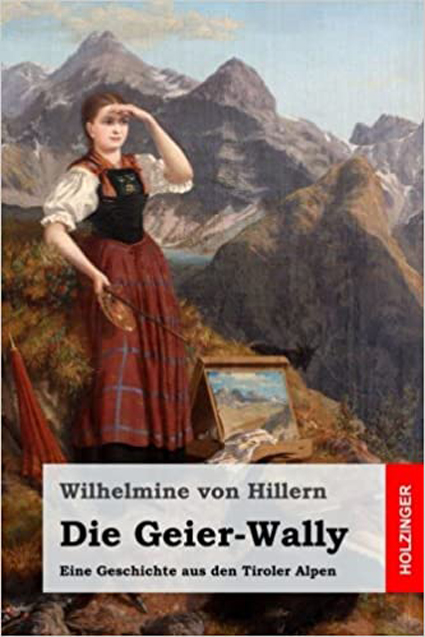

Wilhelmine von Hillern’s novel “Geier-Wally

by Moritz Nestor

You have to read the book, first published in 1873, in the original, it is too well written. Unfortunately, its content was ideologically appropriated, flattened or distorted in numerous movie versions and in even more numerous adaptations for the stage.

Wilhelmine von Hillern based her novel on the life journey of the Tyrolean Anna Stainer-Knittel (1841-1915), a portrait and flower painter. Wilhelmine von Hillern visited her in Innsbruck to get to know her after hearing that Anna Knittel had gutted an eagle’s nest in a rock face near the hamlet of Madau at the age of 17, hanging from a rope. This was a real man’s job, which at that time protected the flocks of sheep. But after an almost unfortunate accident a year earlier and after no man volunteered for the venture, the idiosyncratic Anna Knittel as a woman proved to be quite equal to this man’s task. In this and many other ways, she rejected the traditional image of women and is considered by some people to be an early example of female emancipation. The artistically gifted girl received private lessons at an early age, was supported by an artist, studied for a while at the Munich Art Academy and became a working mother later on. From 1873 until her old age she ran a drawing and painting school for ladies in Innsbruck.

Growing up in a harsh and loveless upbringing

In the novel “Geier-Wally”, the pretty Walburga Strominger grows up after the early death of her mother as the only daughter of the richest farmer in the valley, a domineering, hard man. The maid Luckard is a loving mother substitute for Wally. One day Wally will become the farm heiress. Her father educates her harshly, like a boy. None of the men in the valley dare to clear out a lammergeier’s nest in a rock face. Wally’s father publicly mocks the men of the village as cowards and ropes his daughter down to the vulture’s nest in the rock face. Wally clears out the nest despite the attacks of the mother animal. Scratched and bleeding, with a vulture chick back on top, the proud father kisses her for the first time in her life. Wally raises the vulture chick, hence her nickname “Vulture-Wally”.

At 16, Wally falls in love at her confirmation with the handsome man Joseph, who has killed a bear. But Wally’s father rejects “Bear Joseph”, as he is called, as a son-in-law. He has already promised his daughter to the sinister Vincent and therefore pulls Wally away from the feast and Joseph back home prematurely. When the daughter in love cries for the first time in her life, her unloving father beats her up.

Thanks to a sensitive eye for relationship processes …

Wally detests Vinzenz. Because the father cannot conquer his daughter, he banishes her with her vulture Hansl to a high alp as a herdswoman for sheep and goats. When Wally returns in autumn, her father is ill and Vinzenz is already running the farm. Before Wally’s return, the old Luckard has been chased from the farm after a quarrel and died full of grief about it. The father forbids Wally to live in the house. She has to live as a fodder maid and sleep with the cattle. The humiliated daughter finally loses her temper when Vincent abuses an old farmhand brutally and knocks him down with a hatchet. As Wally is to be locked in the cellar, she hurls a burning log into the hay barn to escape while everyone is busy putting out the fire.

… the author awakens the under-standing for Wally’s inner life path

With great knowledge of human nature, Wilhelmine von Hillern shapes Wally’s life journey through difficult entanglements and strokes of fate. Her Geier-Wally is, in the best sense of the word, a piece of folk literature of the kind that emerged at the end of the 19th century; it need not fear comparison with Jeremias Gotthelf and Peter Rosegger, to name only a few. With a precise eye for the course of relationships and conflicts between father and daughter and between Josef and Wally, the author creates a true education novel centred on the inner development of a misunderstood, harshly and lovelessly brought up girl and her search and struggle for honest love and recognition. It is the classic theme of the education novel in the tradition of Goethe’s “Wilhelm Meister” or Gotthelf’s “Ueli der Knecht” (Ueli the farm-hand): how a person makes his way through life, works his way out of the low points of life by his own efforts, how he learns from his mistakes and conflicts, and finally how he can gain a foothold in the existing society. For the insiders: a true “anti-Adorno”! But that’s just by the by.

There are tragic scenes, struggles for pride and superiority, for love and defiance. For Wally, loving has long been too much associated with being down – until Josef and Wally finally find each other, no longer always seeing the cause of their own feelings in the other, but genuinely forgive each other and live together on the farm for a few more happy years.

“Wally and Joseph died early, the storms that shook them had loosened the roots of their lives”, so the novel ends – a work such as is hardly ever written today. A novel of a vanished world and yet also – in its gripping descriptions of human fates and the search for love in an often cruel world – a timeless work that can make a bygone historical era empathically accessible to today’s young people.

Intuitive anticipation of individual psychological insights

In every line of Wilhelmine von Hillern’s book, one notices how deeply rooted the author is in the culture of her homeland and her era, and how much she lives with the people of her homeland and how much she can empathise and sympathise with them because she knows her people. Woven into this education novel, however, is also a great character portrait, painted with an astonishing amount of psychological understanding.

When Wilhelmine von Hillern wrote her novel in 1876, depth psychology was not yet born. Alfred Adler, the founder of individual psychology, is only six years old and, as one of the three pioneers of depth psychology, will coin the term “male protest” before the First World War.1,2

His pupil Otto Rühle speaks of “protest masculinity”.3 What is meant is that in the climate of cultural dominance of men (equal: above, toughness, strength, valuable) over women (equal: below, weakness, passive, inferior) boys and girls experience an educational climate already in the nursery in which femininity (and thus also mildness, goodness and charity) is devalued as supposedly inferior and an exaggerated “masculinity” (and thus violence, harshness, lovelessness, lust for power and severity) is glorified as supposedly superior.

In this educational climate, already in the first years of childhood – the girl – aligned with this fiction of masculinity like superiority, – toughness and strength – begins to reject her own femininity as supposed social inferiority (male protest) and adopts “male” character traits culturally considered superior in order not to be, as she feels, less “worthy” than the boys considered more valuable by the patriarchy. In this educational climate, the girl quickly develops typical male characteristics, behaves wildly like a boy to show that she is also “good” as a girl, and trains the great mental ambition to outdo all others like a man in order to be considered as woman. In doing so, however, she is driven by the need to do twice as “well” as a man in order to be able to “catch up” with the male world, which is considered to be of higher value.

Typical female figures from politics, culture and history remind us, even today, of this overcompensation of “male” power. More than thirty years before Adler, Wilhelmine von Hillern creates a girl’s fate with her Geier-Wally, marked by the consequences of harsh beating pedagogy and “male protest”. Enmeshed in a tragic struggle and protest against male superiority and harshness, which she also admires, she flounders “in the net of her fiction” of the alleged superiority of men.

If one reads “Geier-Wally” also with an “individual psychological eye”, it becomes quite vividly clear how much Wilhelmine von Hillern anticipated with her vivid character image of Wally Strominger, what the historically later Adlerian individual psychology describes as the tragedy of the hard beating pedagogy and sets out what consequences this can have in the mind of a girl who grows up in the educational climate of the cultural superiority of man over woman.

Pioneer of psychological knowledge of human nature

The Russian writer Fyodor Michailowitsch Dostojewsky once said that one can spend a lifetime trying to solve the riddle of man and still not lose any time doing so, because one does so because one wants to be human. Wilhelmine von Hillern and many other poets, with their intuitive knowledge of human nature, anticipated the scientific findings of the depth-psychological knowledge of human nature of the 20th century to an astonishingly high degree. Therefore, they may confidently be counted among the pioneers of modern depth psychology.

It is, after all, the vivid descriptions of people like Geier-Wally who get caught up in actions of which they can say what they have done but do not understand why they have done it. – They clarify what unconscious feelings and actions are long before the scientific efforts of depth psychologists.

We admire the greatness of these poets and their compassionate power, the foreboding depth of their urgent reflection and their descriptions of the soul. Their interest in and rich knowledge of man. Their respect for even the simplest man, who has long since fallen into social contempt and has been expelled from the human community.

Friedrich Schiller, for example, does not accuse a “common criminal” of being the spawn of a depraved human nature and stirs up base feelings of revenge, as is presented to our children and young people every day in the mass media to an unbearable extent – permeated by the ever same monotonous idea of revenge – but allows the poor devil to be understood as one of us who has lost respect for himself – “criminal of lost honor” Schiller calls him – and thus also for others. Not least through the attitude of his fellow human beings – through our attitude.

Broadening the human horizon

Through such reading one learns to look deeper: behind the prejudiced superficialities of the judgment of time. The poet leads us through the forcefulness of his descriptions of the emotional entanglements to a reading in which one experiences in oneself what the true motive of a despicable act is and: what one has never thought about – and thereby integrates in one’s own emotional view of man a bit more knowledge of man and fellow humanity: Had I been in the place of this novel character, had I been born and brought up and grown up under the same circumstances, had I got into the same entanglements – I would probably have acted similarly or even in the same way as this person there, whom the poet describes to us so vividly close and whom our superficial whipped-up time condemns screamingly. The reader can thus, by reading the poet, escape a bit from the base desire to want to participate in that alluring striving for power through which little souls feel a bit more imagined greatness when they cry out for revenge. Thus, the poet ultimately becomes a teacher of psychological science and of a more understanding inner view of man. Contributing to this is also the merit of Wilhelmine von Hillern, the creator of the Geier-Wally. •

1 Adler, Alfred [1910]. “Der psychische Hermaphroditismus im Leben und in der Neurose” (Psychic hermaphroditism in life and neurosis), in Adler, Alfred; Furtmüller, Carl (eds.) [1914]. Heilen und Bilden.(Healing and educating), Frankfurt/Main 1973, pp. 85-93

2 Adler, Alfred [1912, 1919]. Über den nervösen Charakter. Grundzüge einer vergleichenden Individual- Psychologie und Psychotherapie. (On the nervous character. Basic Features of a Comparative Individual Psychology and Psychotherapy.), Göttingen 1997

3 Rühle, Otto [1925]. Die Seele des proletarischen Kindes. (The soul of the proletarian child.) Frankfurt/Main 1975, pp.16,52, 82ff