A plea for more solidarity

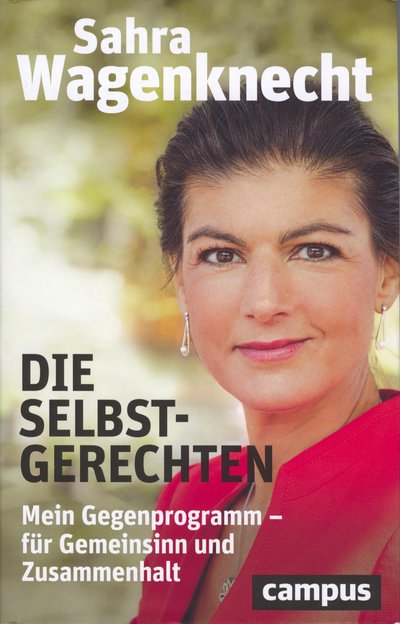

On the book by Sahra Wagenknecht: Die Selbstgerechten. Mein Gegenprogramm – für Gemeinsinn und Zusammenhalt (The Self-Righteous. My alternative approach – towards sense of community and solidarity)

by Carola and Johannes Irsiegler, Gräslikon

When in March 1999 NATO started bombing the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and Germany actively took part in this war, many people all over Europe were appalled. How could it have happened that a Social Democratic-led government would support this first war on European soil since 1945? How could it come to this “major sin of the left” – a left that twenty years ago had demonstrated for peace and social justice and now succumbed to the propaganda salvos of the then Green Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer?

It is the great merit of the German politician Sahra Wagenknecht, to address this development and its effects from a left-wing perspective in her book “Die Selbst-gerechten. Mein Gegenprogramm – für Gemeinsinn und Zusammenhalt” (The Self-Righteous. My alternative approach – towards sense of community and solidarity), published in 2021.

Sahra Wagenknecht is very well known in Germany. She is a left-wing voice who repeatedly comments on various political developments thereby demonstrating a high degree of independence. For years she has been campaigning for social justice and has been a vehement critic of the social cuts of the last decades in Germany – very much in the spirit of a political left position. The daughter of an Iranian father and a German mother grew up in the former GDR. She studied philosophy, modern German literature and economics before completing her doctorate in the latter subject. At the time of the German reunification, she became a member of the PDS party, which later became the Left Party, and was a member of the party’s executive board from 1991 to 1995 and again from 2000 to 2007. From 2010 to 2014, she was Deputy Chairperson of the party, and from 2015 to 2019 Chairperson of the Left Party in the German Bundestag.

The divided society and its friends

Starting with the question why left-wing parties nowadays fail in their ambition to appeal to citizens and therefore to get elected, Sahra Wagenknecht first describes the current state of many Western countries’ societies: “It seems that our society has lost the ability to discuss its problems without aggression and with a minimum of decency and respect. [...] The question therefore arises: Where does the hostility come from that now divides our society on almost every major and important issue?” (p. 10/11) Unlike published opinion, she doesn’t consider the rising right to be responsible for the vitriolic political climate in Germany and the USA: “The rising right is not the cause, but itself the product of a deeply divided society.” (p. 11) Instead, she focuses on the role of the left: “Left liberalism* has played a major role in the decline of our debate culture. [...] Whether refugee policy, climate change or Corona, it is always the same pattern. Left liberal arrogance fuels right-wing gains in terrain.” (p. 13)

She is critical of the self-righteousness in the ranks of those on the left who “had switched sides” (p. 97) and whom she classifies under the term “left liberalism”. They are the “winners of the social changes of the last decades.” (p. 97) According to Sahra Wagenknecht, the increasing split in society is rooted in “the loss of security and common ground”, which was “linked to the demolition of the welfare states, globalisation and the economic liberal reforms”. (p. 14) Globalised, uncontrolled capitalism has turned ordinary people into losers, while the winners are the owners of large financial and business assets and a new academic middle class in the major cities, who represent the actual left liberal milieu. Sahra Wagenknecht disapproves of left-wing parties having abandoned the idea of subordinating capitalism to a legal framework and thus taming it, and instead, adopting the concept of an “unleashed market society” (p. 125) like that of Margret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. “That the former British prime minister once answered the question about her greatest political success with ‘Tony Blair and New Labour’ was [...] an expression of a profound truth.” (p. 125)

The left liberal leadership has continued the policy of social cuts. “The old neoliberalism and the political agenda of unleashed markets and global greed already lost public backing at the beginning of the 21st century. It seems however evident that these policies couldn’t have been continued without the new left liberal backing.” (p. 139)

From her left-wing point of view, Sahra Wagenknecht criticises the path that some left opinion leaders have embarked on in recent decades. They turned themselves into stooges of neoliberalism and globalisation, followed the “third way” of Blair, Jospin and Schröder and gave away their original concerns for peace and social justice. This development already had started in the 1980s with the change from the old social democratic leadership to a younger generation. In pursuing neoliberal economics, turning money into even more money, they have resorted to any means, even war.

How left-wing parties lost focus on social concerns

Instead of focussing on social concerns, left parties today are mainly concerned with “questions of descent, gender and sexual orientation” and the “rules of correct mode of expression.” (p. 99) Sahra Wagenknecht reveals the philosophical background of this “mania” in the theoretical work of French de-constructivists like Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida, pointing out its devastating social consequences: “Identity-politics of left liberalism, which encourages people to define their identity on the basis of ancestry, colour, gender or sexual orientation, not only constructs common interests where there are none at all. It also splits societies where cohesion would be urgently needed. This is achieved by continuously putting alleged minority interests in opposition to those of the majority and by encouraging members of minorities to separate themselves from the majority and to remain among themselves.” (p. 114)

It’s the old principle of domination through ‘divide et impera’! Left liberalism alienates left parties “from the traditional middle class, the working class and poorer non-academics, who are neither socially nor culturally addressed by the liberal-cosmopolite narrative, but – rightly! – perceive it as an attack on their living conditions, their values, their traditions and their identity.” (p. 139) In doing so, the left liberals display arrogance by claiming that their way of life and their convictions be the standard for all. Sahra Wagenknecht is worried about the fact that the left is increasingly losing voters to the right-wing parties, which are “the new workers’ parties.” (p. 175) As long as the political left fails to offer a convincing political programme that not only appeals to the growing number of less affluent academics, but also meets the social interests and values of workers, service employees and the traditional political centre, more and more people from these classes will either turn away from politics or search for a new political home on the other side of the political spectrum.

Not migration, but promote real development

Migrants are among the losers of neoliberalism and globalisation, as they are exploited as cheap labour. “Between countries at a similar level of development, freedom of movement in the choice of where to live and work is a gain in freedom. Between poor and rich countries, on the other hand, it widens the gap, lowers wages in the richer country and worsens living conditions for those who are already disadvantaged.” (p. 169) This truly “cannot be a left project [...]”. (p. 169) Instead of promoting migration, those who really want to promote development and fight poverty on a global level have to go other ways. Ms Wagenknecht mentions as the first and most urgent step “an end to Western wars of intervention and the armament of civil wars through arms deliveries”. (p. 170) She also calls for a trade policy that allows poorer countries to apply what has helped successful economies in the Far East out of poverty: “tariffs to protect their own industries and agriculture, state subsidy policies, sovereignty over their own raw materials and arable land […].” (p. 170) For the refugees in the slum camps of this world, the UN organisations on the ground would have to be provided with significantly more financial resources.

A programme for togetherness, cohesion and prosperity

Sahra Wagenknecht devotes the second part of her book to the question of what needs to be done to find a way out of these social aberrations. She begins by recalling the anthropological foundations of our humanity: “Despite the much-vaunted individualisation of modern societies, human beings are still communal beings. (p. 205) This is in line with the findings of modern anthropology and psychology, which start from the social nature of human beings. The so-called homo economicus, which today’s economists wrongly assume, is an “egoistic being without social references and community ties […]”. (p. 209) On the other hand, for the democratic state to continue to exist, it needs a “fund of commonalities and common values”. (p. 214) Without a sense of community and cohesion, there is a threat of “a society that is ruled by markets and big companies and has said goodbye to the claim of democratic design”. (p. 214) Values such as public spirit, solidarity and co-responsibility are needed. The sources of this thinking are rooted in Catholic social teaching as well as in social democracy. She also sees a positive approach in the economic school of ordoliberalism, the Freiburg School, which subordinated the economy to the rules of the constitutional state and thus founded the successful concept of the social market economy. “The strong European welfare states of the post-war period could not have emerged without such a foundation.” (p. 215)

Community and belonging

Subsequently, Sahra Wagenknecht develops a programme based on community-oriented conservative values. She describes conservative values as, among other things, the desire for stable communities and for belonging. She states: “By anchoring common values, communities create meaning, identity and security. The longing for social bonds is not the result of subjugation, as one of the masterminds of left-liberalism, Michel Foucault, has claimed. The imprinting of man by his history and national culture is therefore also not a prison from which he must be freed.” (p. 224) And she continues: “The stable family is also not a cage, but for many people a dream of life, which the economic environment increasingly makes unrealisable.” (p. 224) She reminds us that the “tamed market economies of post-war Europe [...] were a far more tolerable society for a large majority than the disinhibited, globalised capitalism of our time”. (p. 224) It is a matter of “becoming aware that an orderly world, stability and security in life, democratic societies with a real sense of we and trust in other people […] is not only the past, but can also be the future”. (p. 225)

On the importance of the nation state

As a democrat, Sahra Wagenknecht recognises that the sovereign nation state is the basis for democratic coexistence and only in it the protection of the weaker can be guaranteed: “More democracy and social security can therefore not be had through less, but only through more nation state sovereignty”. (p. 243) National identities cannot be decreed from above, but must grow historically. In this sense, she is also critical of the attempt to “unify the EU by centralising decision-making competences in Brussels […]” (p. 244). In her opinion, the EU should not be dissolved, but “transformed into a confederation of sovereign democracies” (p. 244). For centralist action, instead of more commonality and great European answers to the problems of our time, has produced growing tensions and conflicts.

The individual countries, Sahra Wagenknecht suggests, should follow the Swiss model and allow more direct democracy (p. 267). A genuine democracy must also guarantee and finance the provision of public goods: “Hospitals and universities are not profit centres. Hospitals are supposed to heal. Nursing homes care, schools impart knowledge and universities conduct independent research, and they all need finances, personnel and competence to fulfil this public mission.” (p. 266) She advocates an industrial policy based on sustainable technologies, a re-organisation of monetary relations and a “de-globalisation and re-regionalisation of our economy” (p. 316).

On a global level, Sahra Wagenknecht calls for solidarity-based cooperation based on state sovereignty. She rejects the undermining of nation-state sovereignty through supranational institutions, because this disenfranchises the population and mainly benefits the economic elites. (p. 246)

Sahra Wagenknecht herself describes her book as a proposal for what the left could do better in order to reach more people again, especially those who are not privileged. It is a plea for more social cohesion and a confrontation with those tendencies that stand in the way of this.

If Sahra Wagenknecht succeeds with her book in making politics more oriented towards the common good again, much will be gained for all of us. •

(Translation Current Concerns)

* Translators note: Sahra Wagenknecht is using the German term “linksliberal” to describe politicians, who on the one hand support cultural liberal positions, while on the other hand putting forward economic neoliberal concepts. In the UK this was Tony Blair, in the US Bill Clinton. A translation word by word would mean left liberal, but we know, that Sahra Wagenknecht doesn’t mean “left” in the sense of a leftist point of view like that one of Bernie Sanders.