War on Armenia’s state borders

by Gerd Brenner, Oberst i Gst

Despite the obvious military aggression of Azerbaijan last autumn, Armenia so far hasn’t received anything more than rhetorical support from the so-called Western community of values. The United States and France, as co-chairs of the group of states that has been committed to a peaceful resolution of the Karabakh conflict, have done nothing to stop Azerbaijani aggression. This once again sheds a revealing light on the double standards and weakness of Western foreign policy. Economic interests quickly push aside principles of international law, especially when the geopolitical setting is convenient.

In the past few weeks – largely unnoticed by the Western public – more than just incidents have occurred on the state border between Armenia and Azerbaijan: we can speak of border skirmishes, indeed. Such clashes are especially worrying because they didn’t take place on the disputed border in Nagorno-Karabakh, but on the border between the two states in the South Caucasus recognised under international law.

Dangerous potential for escalation in a geopolitically fragile region

The potential for escalation is enormous in a region where Russia, Georgia, Turkey and Iran share borders. Therefore, it is incomprehensible why the warlike events of the last few weeks have attracted so little attention.

In the Armenian-Azerbaijani war, which ended in 1994, the Armenians and the Karabakhs together conquered the settlement area of ethnic Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh as well as the surrounding areas inhabited by Azerbaijanis. The Azerbaijanis living there fled to the Azerbaijani heartland, where they have since been awaiting their return to their ancestral land in refugee settlements. In the years between 1994 and 2020, Armenia and Artsakh, as the Republic of Nagorno Karabakh has been referring to itself for a few years, developed the conquered territories into a kind of military glacis in which they built strong field fortifications. Again and again, discussions arose as to whether Armenia or the Republic of Artsakh should return these territories to Azerbaijan in exchange for peace. Sceptics pointed out that after such an exchange, Artsakh’s military position would become very precarious because it would then be completely surrounded by Azerbaijani territory. Furthermore, they argued that there was no guarantee that Azerbaijan would remain peaceful after such a territorial swap. Hardliners strongly opposed a deal based on the principle of “land for peace” because they didn’t accept why territories conquered with bloody losses should be returned to the enemy. In retrospect, the current behaviour of the Aliyev regime in Baku proves the sceptics right: Azerbaijan has regained its territories around Nagorno-Karabakh, but it doesn’t seem as if Ilham Aliyev is satisfied with it.

In the border region between Armenia and Turkey, around the famous Mount Ararat, the cold war still hasn’t ended. Basing on a bilateral treaty, Russian border troops have been stationed on the Armenian-Turkish border since 1992.1 Moreover, Armenia and Russia are allies in the Collective Security Treaty Organisation CSTO. This is a clear message from Russia to Turkey: an attack on Armenia would be tantamount to an attack on Russia, which operates an airbase in Armenia and has stored the equipment for a motorised rifle division.2 Russia is both willing and able to repel a Turkish attack.

OSCE peace efforts

In an attempt to find a peaceful solution to the conflict, in 2007 a group of OSCE participating States formulated the so-called Madrid Principles, which envisaged the return of the Azerbaijani-inhabited territories conquered in 1994 from Artsakh to Azerbaijan.3 Only the so-called Laçin corridor, a strip of land a few kilometres wide, was to remain under the control of the Republic of Artsakh. It connects Nagorno-Karabakh with Armenia representing a kind of umbilical cord between Artsakh and the Armenian motherland.

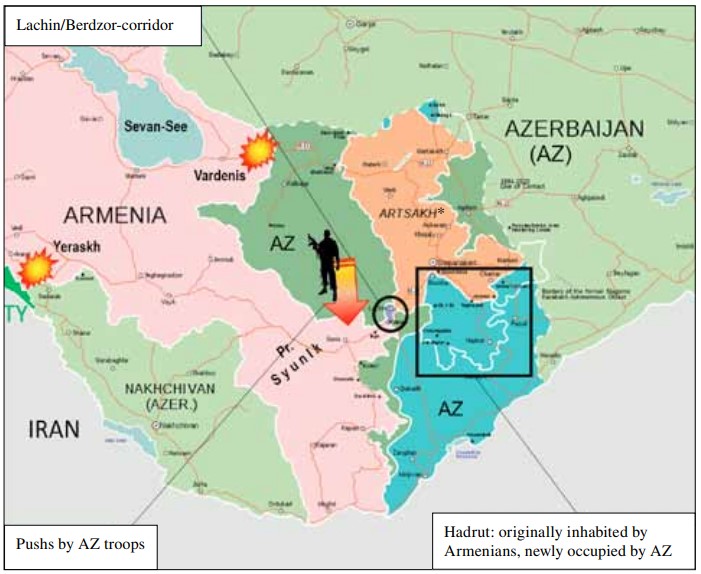

In the six-week war from 27 September to 8 November last year, the Azerbaijani army recaptured large parts of the “glacis”, captured the symbolically important town of Shusha/Shushi and conquered part of the Hadrut district.4 Hadrut had always represented part of the core of Nagorno-Karabakh and had been inhabited by ethnic Armenians. After the Russian-brokered ceasefire of 9 November last year, the inhabitants of Hadrut had to leave their old homeland, because a peaceful coexistence of Armenians and Azerbaijanis is out of the question in the foreseeable future.5 On both sides of the front, a generation has been growing up since 1994, educated in hatred and fear of the respective opposing side. Under the slogan “preparing peoples for peace”, Western diplomats tried to persuade the parties to the conflict to abandon atrocity propaganda, fully aware that it could take years or decades to reduce mutual mistrust and fear.6 With the conquest of the Hadrut district, Ilham Aliyev has now shown the West what he thinks of peaceful conflict resolution.

Russian peacekeepers to secure the state existence of Artsakh

In the ceasefire of 9 November 2020, Artsakh had to cede the territories it had captured in 1994 to Azerbaijan, but retained the Laçin corridor. Shortly after the agreement was concluded, Russian peacekeeping troops moved into Nagorno-Karabakh. They are now stationed in the remaining territory of the Republic of Artsakh for a period of at least five years. After that, according to the terms of the ceasefire agreement, a decision will be made on their continued presence or replacement by an international peacekeeping force. Attacking the Russian peacekeepers would cost Azerbaijan dearly, both politically and militarily, and would completely destroy any remaining sympathy. The Russian peacekeepers thus became the second “tripwire force” in the South Caucasus after the Russian border troops, and Russia became the guarantor of the state existence of the Republic of Artsakh. Over the next five years, the Russian peacekeepers prevented Aliyev from regaining control of all of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Azerbaijan: calculating with ceasefire violations

In recent weeks, there have been far more than mere incidents on the border between Armenia and Azerbaijan, which in many cases is unmarked and runs through confusing terrain. For example, Azerbaijani troops apparently advanced several kilometres into Armenian territory in the Armenian province of Syunik.7 On 20 July, the village of Yeraskh in the tri-border area between Armenia, the Azerbaijani enclave of Nakhichevan, Turkey and Iran came under fire.8 And at the end of July, two Armenian settlements near Vardenis on the south-eastern edge of Lake Sevan became the scene of fighting.9 All these settlements are undisputed territory of Armenia and not disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh under international law.

The events of the past weeks show that Ilham Aliyev wants more than he got in the ceasefire agreement of 9 November 2020. The Russian peacekeepers are preventing him from seizing the remaining territory of Artsakh by force and expelling the last Armenians from his country. Therefore, he wants to conclude a peace treaty with Armenia in which the latter recognises Azerbaijan’s sovereignty over Nagorno-Karabakh. If such a peace treaty is concluded, Aliyev can demand that Russia withdraw the peacekeepers. The method he wants to use to persuade Armenia to take such a step is military force. Reversing the motto “land for peace”, he wants to force the Armenian government to give in by striking Armenian territory by 2025 at the latest. Coupled with further measures to isolate Armenia economically, this method could well lead to success.

Armenia – once again pawn sacrifice of power politics?

Armenia noted with disappointment the Western silence in the face of Azerbaijan’s open military aggression last October and would also have wished for an earlier intervention by Russia. Like its neighbour Iran, Armenia must slowly come to the realisation that even blatant violations of international law do not trigger countermeasures by the international community if there is a lack of political will to do so. And this, in turn, is often a function of geopolitical ambitions.

In Armenia, there is also growing concern about missing Armenian soldiers, and the suspicion arises that Azerbaijan has so far not exchanged all prisoners of war as contractually agreed, but is still holding back a number of them in order to blackmail Armenia.

Armenia’s borders with its neighbours Georgia and Iran are still open. Aliyev would like to close these borders, too. Western pressure on Iran is just what he needs, as are tensions between Russia and Georgia. For Armenia, the future prospects are bleak. For the next five years, it can expect little more than economic pressure and small-scale warfare on its borders, and at best rhetorical support from the West. •

1 The basis for this is the “Treaty between the Republic of Armenia and the Russian Federation on the Status and Operating Conditions of the Border Troops of the Russian Federation on the territory of the Republic of Armenia” of 30 September 1992, Russian. “Договор между Республикой Армения и Российской Федерацией о статусе и функциях пограничных войск Российской Федерации, дислоцированных на территории Республики Армения”, online at https://docs.cntd.ru/document/1900722 and https://www.kavkaz-uzel.eu/articles/280284/. See also “О пограничных войсках” on the homepage of the National Security Service of Armenia, https://sahmanapah.sns.am/ru/%D0%BE-%D0%BF%D0%BE%D0%B3%D1%80%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B8%D1%87%D0%BD%D1%8B%D1%85-%D0%B2%D0%BE%D0%B9%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B0%D1%85

2 See Ирина ПАВЛЮТКИНА: Министр обороны Республики Армения Сейран ОГАНЯН, Россия - исторически наш стратегический союзник, in: Красная звезда, 20 March 2009. The base remains contractually in place for the time being until 2044. Cf. also the homepage of the Russian Ministry of Defence. Ministry of Defence: "Министры обороны России и Армении подписали Соглашение об Объединенной группировке войск двух стран", 30 November 2016, online& at https://function.mil.ru/news_page/country/more.htm?id=12105072@egNews#txt and Алина Назарова: Российская база под Ереваном заработала в "сирийском" режиме, 2 декабря 2020, online at https://yandex.ru/turbo/vz.ru/s/news/2020/12/2/1073492.html?utm_source=yxnews&utm_medium=desktop. On the Erebuni airbase also homepage of the Russ. Ministry of Defence: На российскую авиабазу в Армении поступила партия современных вертолетов, 8 December 2015, online at https://function.mil.ru/news_page/country/more.htm?id=12071115@egNews#txt

3 See CSS Studies on Security Policy: Nagorno-Karabakh, Obstacles to a Negotiated Settlement, No. 131, April 2013, online at https://css.ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/gess/cis/center-for-securities-studies/pdfs/CSS-Analysen_131-DE.pdf. The so-called OSCE Minsk Group consists of Belarus, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Finland and Turkey, as well as Armenia and Azerbaijan. According to the rotation principle, the three states of the OSCE Troika are also permanent members. The group is co-chaired by the USA, France and Russia.

4 For an overview see Halbach, Uwe. “Nagorny-Karabakh”, in: Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung of 26 November 2020, online at https://www.bpb.de/internationales/weltweit/innerstaatliche-konflikte/224129/nagorny-karabach. On the much mentioned use of drones, see: Wissenschaftliche Dienste des Deutschen Bundestags, Dokumentation zum Drohneneinsatz im Krieg um Bergkarabach im Jahre 2020, o. O. 2021, online at https://www.bundestag.de/resource/blob/825428/5b868defc837911f17628d716e7e1e1d/WD-2-113-20-pdf-data.pdf

5 The text of the treaty at З аявление Президента Азербайджанской Республики, Премьер-министра Республики Армения и Президента Российской Федерации 10 ноября 2020 года, online at http://www.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/64384, engl. Translation at Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung of 1 December 2020, Documentation: Ceasefire Agreement between Azerbaijan and Armenia of 10 November 2020, online at https://www.bpb.de/internationales/europa/russland/analysen/322104/dokumentation-waffenstillstandsvereinbarung-zwischen-aserbaidschan-und-armenien-vom-10-november-2020.

6 The author himself took part in corresponding talks.

7 See Brenner, Gerd. “Caviar and war in the Caucasus, venality and greed for power do not let the region rest”, in: Current Concerns No. 12/13, 8 June 2021, online at https://www.zeit-fragen.ch/en/archives/2021/no-1213-8-june-2021/caviar-and-war-in-the-caucasus.html and https://www.fr.de/politik/rote-linien-am-schwarzen-see-90612220.html as well as https://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/ausland/neue-spannungen-zwischen-armenien-und-aserbaidschan-17341621.html

8 See https://twitter.com/NKobserver/status/1417255693107834881. See also Latton, Marcus. “Nagorno-Karabakh is not enough”. In: Jungle.world 30/2021 of 29 July 2021, online at https://jungle.world/artikel/2021/30/bergkarabach-ist-nicht-genug

9 See Gyulumyan, Gevorg. “Fighting on the Armenian-Azerbaijani Line of Contact Halted”. In: The Armenian Mirror Spectator of 28 July 2021, online at https://mirrorspectator.com/2021/07/28/fighting-on-the-armenian-azerbaijani-line-of-contact-halted/ and Ghazanchyan, Siranush. “Armenia downs Azerbaijani Aerostar drone near Vardenis”. In: Public Radio of Armenia of 30 July 2021, online at https://en.armradio.am/2021/07/30/armenia-downs-azerbaijani-aerostar-drone-near-vardenis/