Lessing and his Ring Parable – a masterpiece of true tolerance

The central metaphor in Lessing`s “Nathan the Wise” is surprisingly relevant today

by Dr Peter Küpfer

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing was born into troubled times in 1729. Unlike many of his contemporaries he was not willing to put up with the alleged automatism of inherited or copied prejudices constantly hampering with or preventing cooperation, creating quarrels, fights and eventually wars instead. His whole impressive life was influenced by the question how dogmatic viewpoints and presumptiousness evolve and how human reason should deal with that. In his “Nathan the Wise” he gave an answer to that question. It has remained valid ever since. Facing increasing tendencies towards intolerance again in our times, with discrepancies in factual, political or religious viewpoints threatening to escalate into “ideological wars”, reminding ourselves of Lessing is a blessing and comfort.

Lessing was born as the son of a Pietist pastor in the small provincial town of Kamenz in Lusatia (Saxony). His father, himself an orthodox Lutheran, had always believed in the reconciliation of reason and Christian ideals. He took Ephraim, the second name of his third-born son, from the Old Testament. This act alone may be regarded as a stance for religious peace in a time when anti-Jewish pogromes where events of the not too distant past. His son displayed similar courage in his later life.

At the university of Leipzig the bright young man had initially enrolled for theology but switched to medicine soon. While the era of Enlightenment was just beginning and many literary journals were founded it didn’t take long for the enthusisastic reader to decide that he wanted to make a living as an independent scholar – a heroic plan in a time when the protagonists of literature (and music and painting) ususally had to rely on the support of noblemen as their patrons. Because a free market place of arts as we know it today was only just beginning to develop in those year prior to the French revolution.

After he had moved to Berlin and established intensive contacts with the scholars and writers working towards enlightenment there, Moses Mendelssohn among them, Lessing earned his magister grade in Wittenberg and returned to Berlin in 1752. There the polyglot young writer translated some texts of Voltaire as well as some treatises written in French by Frederick II. The exchange of letters with his friends from Berlin and other writers lead to his publication of the “Letters, Concerning the Newest Literature”. During the Seven Years’ War the writer who often experienced financial hardship was serving as a secretary for the Prussian General von Tauentzien, so that he witnessed the cruelties of 18th century warfare first hand. This had not been the first time – as a young pupil in Meissen he witnessed how during the siege of the city in the Second Silesian War injured people were locked and left without any help in their houses that were destroyed by bombshells because the magistrate feared an outbreak of the plague. Lessing’s comedy “Minna von Barnhelm” which is still well-loved on the stage today was the result of his approach to these war time experiences from a more optimistic angle.

Lifelong struggle against prejudices

The young playwright always had to overcome obstacles. His talents, his broad education, his openminded curiosity and his elegant, sometimes sarcastic style of polemic writing do only too often collide with the necessity to make a living as a writer. Translations, theatre critiques, book reviews, his first own plays provide for some income but not enough to avoid the accumulation of debts. Some theatrical attempts are economically unsuccessful. This includes a play titled “The Jews”, in which the young Lessing transports some thoughtful messages under the disguise of a comedy. Already in this early work Lessing diagnoses self-imposed restrictions of thought, that should be replaced by an openminded perception of reality, as the underlying cause of the persecution of Jews in European history. When he composed his main play “Nathan the Wise” a few years before his death, Lessing would draw on this early comedy.

His tragedy “Miss Sara Sampson” was one of the first plays in the High-Dutch tongue in which ordinary, common people rather than only kings and nobility (as required by the still influential doctrine of French classical drama) were experiencing fateful conflicts on the stage so that the audience were able to identify themselves with the humane acts in real empathy.

A first long-term position which enabled him to pursue his goals was his employment at the recently founded National Theatre in Hamburg – these were years with many ups and downs which saw the publication of his highly influential essay “Hamburg Dramaturgy”. A certain consolidation in his personal financial situation came when in 1770 the Duke of Brunswick made Lessing his librarian in Wolfenbüttel, the most famous library in Germany at that time, a position he held until his death in 1781. He got married, but lost his son and his young wife shortly after childbirth. In 1772 he completed his play “Emilia Galotti”, well-known to this day, in which Lessing shows the moral corruption of a luxurious court in an Italian setting – the resemblance to their own counterparts was only too clear for the German audience. Again the play failed at his time, but it impressed Schiller whose early work “Intrigue and Love” (premiered in 1783, six years before the French Revolution) picked up the theme and became a huge success eleven years later, with its storm-and-stress style castigation of absolutist arrogance and corruption of German princes of the rococo era.

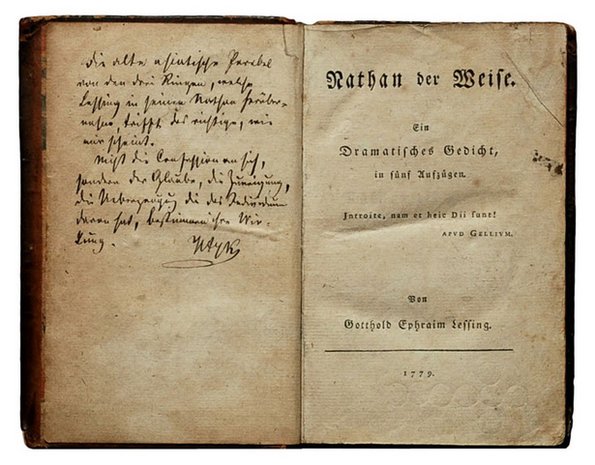

“Nathan the Wise” – Lessing’s legacy

As part of his duties as librarian Lessing published texts and text fragments from the bibliophile treasures at Wolfenbüttel. He preferred authors who were dedicated to realism and reason. But when he published the papers of the recently deceased college professor Hermann Samuel Reimarus from Hamburg under the title “Wolfenbüttel Fragments” this caused an uproar. This author argued for the notion (considered insulting by traditional-minded theologians) that the bible was not the word of God but a text composed by human beings, that Jesus was not the son of God, but a human being who corresponded with the Messianic expectations of his time, the teachings about the resurrection a mere product of the disciples’ imagination. For this publication Lessing was viciously attacked by many public figures, most notably the pastor Melchior Goeze from Hamburg who interpreted the publication as a full-blown assault against religion which he felt obliged to sharply counter-attack in several pamphlets of his own. Those were again answered by Lessing and a public war of polemics broke out. Finally, the Duke of Brunsvick quelled the quarrel by putting a gag order on his librarian. Lessing however did not give in so easily and decided to explain his viewpoint in a play, “switching from the pulpit to the stage” as he wrote in a letter. This is how his “Nathan the Wise” came into being, his legacy in the question of religious and interpersonal tolerance, a play which has remained present on the stage to this day and in which Lessing relates to the forces towards our human nature as social beings by means of the theatre.

Theatre of war

The plot is set in medieval Jerusalem during the Crusades. This is where Christianity, Jewry and Islam have coexisted for centuries. The bloody conquest of the city by the Christian armies and their violence against the Jewish and Muslim populations are still well remembered. At present the wise government of the idealised Sultan Saladin aims to calm down any conflicts between the religious groups before violent hatred may erupt. The author’s intention had obviously been to paint the representatives of the three main monotheistic religions – Christianity, Jewry and Islam – in different colours. Sultan Saladin fulfils the role model of the wise ruler in Lessing’s play, the political leader and religious head of the Islamic ruling elite (a figure, modelled after the contemporary French and German protagonists of Enlightenment). His counterpart is the wealthy Jewish merchant Nathan, whose attributes are again humanity, solicitousness and wisdom. Unlike these two positive representatives of their respective religions and their “humanistic” actions the representative of the Christian religion, namely the Patriarch residing in Jerusalem, is a negative figure. The religious leader of the Christian invaders always suspects the Jews of committing crimes and shortly prior to the climax of the play puts up a scheme to have the well-respected Jew Nathan executed for alleged religious blasphemy. The youthful hero of the play, the Frankish knight Templar Curd von Stauffen (who is referred to as “Templar” in Lessing’s play), who had participated in the crusade but had been kept as a prisoner and had lost contact with his retreating comrades, is also full of Christian prejudices initially against the Jewish population of Jerusalem. It is only when he gets to know Nathan and his family and the love story evolves from this encounter that he wakes up to a reality so much different from what he had expected. Thanks to his dramatic skills as a playwright Lessing succeeds in unfolding the plot from its starting point in an enthralling sequence of scenes and acts towards the quintessential insight for the audience.

Fates of human beings

Nathan has just returned from a long business journey with his caravan. To his horror he learns that his daughter Recha had almost died in a fire incident in his house. She had been rescued by an unknown Templar who risked his own life while saving hers. This was the young Christian knight mentioned above.

Nathan, still shocked by the news, wants to rush to find the young Templar to show his gratitude but Recha doesn’t know where to look for him. Before he accomplished his life saving act he had been captured after a battle by Saladin’s troops and would have shared their fate of the death sentence – but his face looked familiar to Saladin who spared him because the young man reminded him of his late brother Assad who had been killed in a previous fight. Aimlessly wandering around he eventually comes back to the house where he had saved the “Jewish girl”, as he puts it. Nathan approaches him full of gratitude but the knight rejects him harshly, refusing any approval or thanks from a Jew. At last Nathan can persuade him to enter the house to meet his daughter.

In the meantime at Saladin’s palace we are informed about the increasing financial difficulties of the Sultan by a dialogue between Saladin and his prudent sister Sittah. They are not caused by luxurious spending but by the dire situation of the people whom Saladin tends to help as much as he can with cash from his rapidly vanishing treasure. There is only one who can prevent the state from going bankrupt, the Jew Nathan with his vast private fortune. But is he to be trusted? Saladin decides to test his character, summons him to the court and poses the question for the true religion to him. If religion reveals the truth, Saladin argues, as all three of them claim, then not all of them can be equally true since they all confess the same god.

Therefore, which of the three religions is true? Nathan realises the catchiness of the situation. An old tale springs to his mind, the one about the three rings. The wisdom of this tale will not only save himself, but will also do good services to the Sultan. This tale is told in Lessing’s Parable of the three rings, a crucial scene in the history of High-Dutch drama.

The Ring Parable

Not only because it is written in the very middle of the text the parable stands at the centre of the play. This is how it goes:

Once upon a time a “man living in the East” owned a precious ring of inestimable value. The stone was an opal that shimmered with a hundred beautiful colours and had the power to make its wearer loved by God and by men as long as he wore it in the confidence of its power. The man wanted this wonderful ring to stay in his family forever and decreed that it should always pass to the most loved son.

In the course of generations, the ring finally arrived in the possession of a father with three sons, all three of whom he loved equally. From time to time he favoured the one or the other and in moments of weakness he told each of them in turn that the ring would be theirs. When the father’s death drew close he realised the difficulty he was in. It pained him to think of the hurt he was going to cause to two of his sons.

He sent for an artist and ordered at great cost two exact copies of the ring to be made. Even the father could not tell the rings apart. One at a time he called his sons and gave each one his special blessing and a ring. Then he died. After much argument between the sons as to who had the true ring, they laid their case before a judge. Each one of them swore that he had obtained the ring direct from his dying father’s hand.

The judge ruled as follows:

If you can’t produce your father to testify I will have to reject your complaints. Are you waiting until the true ring opens its mouth? I hear that the true ring has the power to make its bearer loved by God and by men. At the moment you each seem to love yourselves more than anyone else. Perhaps all the rings are a fake, perhaps the true ring was lost and your father just made three copies. If you just want my judgement: go away!

If you want my advice: accept the matter as it is. Since each of you has received a ring from your father you believe that you alone have received the true ring. It is possible that your father couldn’t stand the tyranny of the one ring in his house. Each of you is straining to display the power of the stone in his ring! This power will come to your aid with meekness, with heartfelt tolerance, with good works, with the sincerest devotion to God. Perhaps the power of the stone may only express itself to your grandchildren and their descendants.

“Let each endeavour

To vie with both his brothers in displaying

The virtue of his ring; assist its might

With gentleness, benevolence, forbearance,

With inward resignation to the godhead,

And if the virtues of the ring continue

To show themselves among your children’s children,

After a thousand thousand years, appear

Before this judgment-seat – a greater one

Than I shall sit upon it, and decide.

So spake the modest judge.”

(Lessing. Nathan the Wise, Act III, Scene VII)

“Brother love binds man to man”

Saladin is deeply touched by the parable and expresses his hope to become Nathan’s friend, a state loan will testify to their friendship. However, the developments of human fate take a dramatic turn at this point.

The Knight Templar finally gives in to Nathan’s invitation and visits Recha, somewhat reluctantly. Sure, enough he falls in love with her – nature’s revenge for the prejudices, from his upbringing, against the daughter of the Jew. He learns from Recha’s friend and former Nanny Daja that Recha is not Nathan’s own daughter but was adopted after her Christian parents had died. In this conversation he is also made aware of the fact that Nathan did not raise Recha according to the rules of the Christian Church. Being a Crusader, he is enraged by this news which he interprets as preventing a Christian child from her religious rights and he informs the Patriarch about the issue, who in turn suspects a crime having been committed against a Christian baptised into the true religion. He wants to sue Nathan and keeps reiterating the fanatic sentence: “The Jew must burn!”

Towards the end of the philosophical drama all the fateful entanglements are untied one by one. The Patriarch and also the young Templar are put to shame when the truth is revealed. Nathan has not raised Recha as a Christian but according to the ethics of humanism. According to his convictions about respecting the child as a person he waits until Recha will learn the circumstances of her family and will decide for herself which religion to adhere to. The knight must admit that his choleric temper had prevented him from acknowledging the truth. Piece by piece the puzzle is put together to reveal the full picture: when Jerusalem was sacked by the Crusaders Nathan’s wife and his seven sons were among those who perished as “collateral damage”. Nathan however would not give way to despair but only a few days later, when he heard about the little child of a Christian mother who had died shortly after childbirth, he had the greatness to adopt Recha, the child, and to accept her as a gift from god. Research, documents and witnesses reveal what Nathan had suspected for some time: the young knight Templar is also a son of Recha’s father. Finally, as his complexion already hinted at: His father whom he had never met was Saladin’s late brother, who apparently had lived in Germany several years under the alias Wolf von Filnek.This makes Recha and the Templar siblings who have found in Saladin and Nathan, if not natural fathers, but caring and considering father figures. Friendship and natural bonding have overcome enemy stereotypes nurtured by centuries of wars.

Symbolically the end of the play shows what is true for humanity as a whole according to Lessing: Brother love binds man to man, or at least should do so, as the first article of the Declaration of Human Rights demands today, much later and after several more wars: they should meet in the spirit of brotherhood and ban wars as a means to achieve their goals.

Truth will out

For many people the Ring Parable has become a metaphor for religious tolerance. Just as the three rings are indistinguishable for the observer, in the same way no religion should pretend to represent the one and only truth, Lessing argues. Truth cannot be possessed but has to reveal itself, people have to strive for it – but never with violence or war. Another dimension of the Ring Parable opens here, which is less often focused upon but which is essential to grasp its full meaning: Lessing’s message does not only mean that all three monotheists religions are just equal as religions. This is part of its meaning but it does say more. The ones who carry the real ring, in other words those who are convinced to know how people should live must not just settle morally in this conviction. Neither must they force it on other people, as the negative example of the Patriarch shows as well as the catastrophic prelude to the plot. On the contrary they need to prove with their deeds that they do in fact carry the “real ring”. The real ring has the ability to “make its wearer loved by God and by men”. During the time of absolutism this could indicate that the just, humane, the enlightened ruler would be the one who made him- or herself loved by the people, i.e., his or her subjects. The ruler had to govern in a mild, humanistic and just manner.

In our modern times the Ring Parable even grew in importance. Not only are the bearers of the real ring the religious and secular authorities competing and striving for justice, good laws and good governance today – in times of established or developing democracy the bearers are the people themselves, the family of humankind living together on this planet. Peaceful competition should have its place here, the ambition to prove before history, i.e., before the people, that one is worthy to bear the real ring. Or better – one would be worthy to carry it. Because modern human beings no longer need to rely on ring magic, one must become the seed of the common good oneself. This is the wisdom of the Ring Parable today. One could confine it to the realm of fairy-tale dreams where it doesn’t do any damage. Or one can try to live according to it instead. Then the daily question would be not so much who is right or wrong in their view on life and the people, but who can carry oneself and humankind a step further towards a good and humane life – for all of us. Once more it is about each individual – and even better, cooperative contribution to promote the common good worldwide. Lessing does not call for heroic deeds but for the strive towards humanism in all of us – with as little prejudice as possible, and on a daily basis. •

“… to whom it is enough to be a man”

pk. Curd von Stauffen, the youthful hotspur and knight Templar is in the beginning still influenced by his prejudices and feelings of being appalled by all Jews including Nathan. The latter confronts these prejudices with his wisdom that not the religious confession is what counts, but the manner how human beings interact with their fellow human beings even if he believes in different dogmas. Not the confession counts but the way of living in humaneness.

Nathan: […] I know how good men think – know that all lands

Produce good men.

Templar: But not without distinction.

Nathan: In colour, dress, and shape, perhaps, distinguished. […]

Templar: Well said: and yet, I trust, you know the nation,

That first began to strike at fellow men,

That first baptised itself the chosen people –

How now if I were – not to hate this people,

Yet for its pride could not forbear to scorn it,

The pride which it to Mussulman and Christian

Bequeathed, as were its God alone the true one, […]

Where, when, has e’er the pious rage

To own the better god – on the whole world

To force this better, as the best of all –

Shown itself more, and in a blacker form,

Than here, than now? To him, whom, here and now,

The film is not removing from his eye –

But be he blind that wills! Forget my speeches

And leave me.

Nathan: Ah! indeed you do not know

How closer I shall cling to you henceforth.

We must, we will be friends. Despise my nation –

We did not choose a nation for ourselves.

Are we our nations? What’s a nation then?

Were Jews and Christians such, e’er they were men?

And have I found in thee one more, to whom

It is enough to be a man? […]

(Lessing. Nathan the Wise, Act II, Scene V)