“I had to get along with them”

Gontran de Poncins’ “Kabloona”

by Moritz Nestor

“Kabloona” is the word of the Eskimos of the Arctic for the “civilised” whites. The French ethnologist Gontran de Poncins, whose real name was Jean-Pierre Gontran de Montaigne, Vicomte de Poncins, i.e., a descendant of the great European pedagogue Michel de Montaigne (1533–1592), wrote down the wonderful travelogue “Kabloona” in 1938. He had lived among Eskimos for two years. Like one of their own.

“Kabloona” tells of how, in a few months, Frenchman Poncin manages to shed the civilisational habits of millennia and live with the polar natives, at a normal temperature of forty degrees cold and a diet of snow water, raw iced fish and seal meat. The book is a gripping account of a journey into the Ice Age, the story of the collision of two worlds and ways of thinking. Gontran de Poncins does not lose himself in conjecture and reflection: He presents facts, conscientiously records what he experienced, and reports observations and experiences from the lives of these people.

The most difficult thing for the European nobleman Gontran de Poncins, however, was not the privations at forty degrees below zero, but “the Eskimo way of thinking. You couldn’t get along with them unless you tried to communicate with them in their own language; and I wasn’t a tourist for whom these are trivial things, but I was dependent on the help of the Eskimos. I had to get along with them.” (p. 10) What a humane frame of mind: we humans have to get along. What kind of world would it be today, one thinks involuntarily in view of this attitude of the French ethnologist, which runs through his travelogue like a red thread, if we Europeans had been able to live this basic human attitude instead of “discovering”, “christianising” and “civilising” other continents, cultures and "wild" peoples for centuries – and today “democratising” and bombing and starving them in the name of human rights!

The human attitude of this ethnologist from the year 1938 actually applies to the encounter with every human being! One cannot get along with any human being, with any people and with any culture, to say it in the words of Poncin, “unless one tried to communicate with them in their own way of expression”! The extreme conditions of the inhospitable ice desert of the Arctic exert a particularly high pressure on the people who want to (survive) live in it. So that, one would like to think, Gontran de Poncins was left with not much more than the insight: “[...] I was dependent on the help of the Eskimos. I had to get along with them.” But it was not the external pressure of the inhospitable icy desert that ultimately pushed the French ethnologist to this equal peaceful attitude toward a foreign culture. Gontran de Poncins describes that the decisive thing was the work on himself and the change of his inner attitude. For the priests, trappers and hunters, who at that time had to survive under the same extreme climatic conditions as the ethnologist, he describes, the Eskimos were “without exception all ‘worth nothing’”. These whites, calling themselves civilised and Christians, “live the life of the Eskimos, but only up to a point. They travel on sledges, haul fish from under the ice, wear furs, and build snow houses (igloos), though rarely. But into the spiritual Eskimo world they never ever penetrate.” Between them and the Frenchman there is “the essential difference that I had come here to penetrate a world which was indifferent to them [the Kabloonas].” (p. 21f.)

Thus, this book is much more than the truly grippingly written travelogue of a Frenchman on the eve of World War II. It contains a wealth of descriptions of inner learning processes. They also make the book a lively educational book: a European nobleman – standing for all of us “Kabloonas” – faces the task of an inner confrontation with himself and his own cultural prejudices while getting to know another culture. He overcomes the high horse of the conceited, who can approach other cultures at most as a “tourist” and who is not interested in the intellectual world of people who are foreign to him. Thus, Kabloona also reads as an educational novel for learning to live peace and understanding among cultures. At the beginning of World War II, a small light of peace in difficult times. And a worthy homage to the attitude of tolerance of Poncins’ famous forefather Michel de Montaigne, who once admonished that only by empathising with others would people be able to truly understand not only their own being, but also that of others. While the Anglo-American power elites are pushing ahead with nuclear armament at a breath-taking pace, thus threatening and terrifying the world, the humanistic ethos of the two Montaignes from “old Europe” immortalised in “Kabloona”, which those terror-spreading simple-minded power elites derisively dismiss, is more urgent today than ever: “I had to get along with them.” •

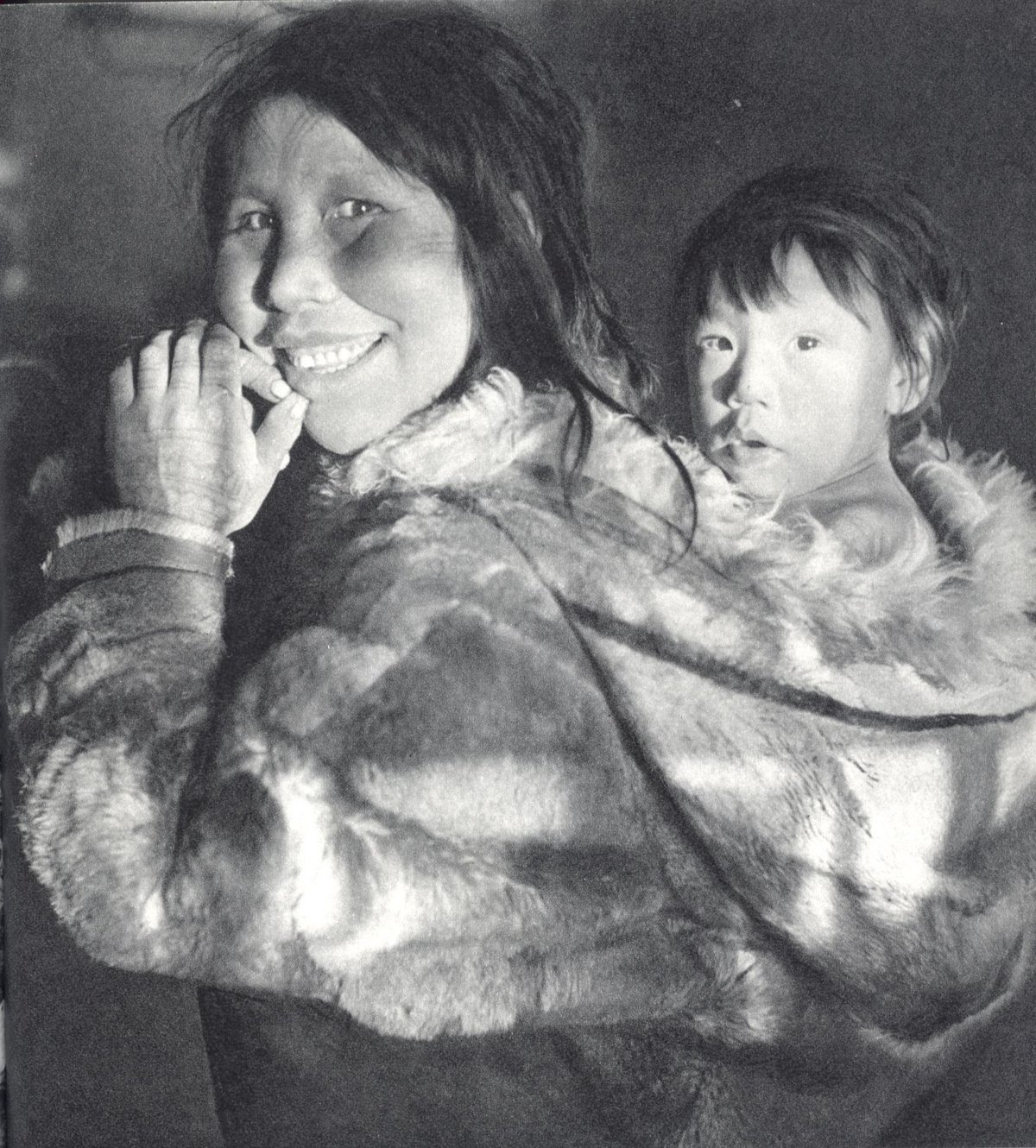

(Caption and picture from the book by Gontran de Poncins. Kabloona)