“Let’s have merry things – I vow that all my paintings shall be pleasant”

Valentin Serov – Portrait painter of the late Czarist period and bucolic impressionist

by Winfried Pogorzelski

Without much ado Alfried Nehring, author of an illustrated biography of the painter Valentin Serov (1865−1911), jumps right in medias res: In 1887, the 22-year-old Serov is on his grand tour through Italy and describes his impressions of the light-filled Mediterranean country enthusiastically to his bride; on this occasion he pens down the ultimate goal of his art: “In this century of ours only cruel topics are painted, nothing pleasant. I prefer merry things and vow only to paint what is pleasant.”1 Valentin Serov, pupil and friend of Ilja Repin, the famous painter of realism, is an important representative of Russian painting who took glamour and daily routine of the Czarist period as his motives and excelled in portrait painting. He introduced Europe to Russian painting and was a co-founder of the school of classic modernity.

Despite numerous publications about Valentin Serov which were printed in Russia but also abroad only a few art lovers in Europe are aware of him and his outstanding oeuvre. Thanks to Alfried Nehring this community is now increasing. The author succeeds with his 90 pages book, which includes images of many paintings and drawings of Valentin Serov but also photographies, to acquaint the reader with life and work of this extraordinary artist. Twelve phases of his eventful life are shown in episodes, some of which shall now be sketched out in this article with special consideration of outstanding artworks

Early beginnings of the future artist

Valentin Serov is born in 1865 into a family of artists: His mother is a pianist, the father is an opera composer and music pedagogue; their house in St. Petersburg is an important place for artists to meet. They have regular soirees where actors, students, opera singers, musicians, and artists – including Ilja Repin – get together. These were occasions of vivid discussions about literature, art and society, about the nihilists and women’s rights – and of playing music together. After finding out early about Valentin’s drawing talent, his parents make it one of their priorities to foster his gift. The eight-year-old boy gets lessons from Karl Köpping, painter and engraver in Munich, where he is also introduced to the treasures of the art collections.

The encounter with Ilja Repin, the most important representative of Russian realism, proves to be of major significance for Valentin’s development. When Repin spends some months in Paris, the centre of French impressionism, Valentin’s mother follows the advise of one her artist friends that he would be the best teacher for Valentin and follows him to the French capital with her son. The young boy is eager to learn from his hero, such as how to draw with the pencil, the right approach to oil colour painting and much more.

Back from Paris the family become acquainted with Savva Mamontov, a wealthy patron of the fine arts who became rich with railroad building. North of Moscow he has turned his estate Abramtsevo into an artists’ colony. This is where Valentina Serova settles with her son. In constant interaction with other artists and guided by Ilja Repin the young painter can steadily develop his skills. He tries out landscape painting but already starts what would later become his domain of excellence, portrait painting. In these circles people liked to have portraits made of themselves, not the least in order to establish themselves as patrons. Here Valentin also meets his future wife Olga Trubnikova for the first time, a foster child of his aunt Adelaida Semjonovna Simonovich. Together with Repin he visits the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, they travel to South Russia and Crimea together. Destinations of more travels, specifically for the purpose of furthering his development in the arts, are Munich, the Netherlands, Belgium, Berlin, Dresden and finally Italy. In 1880, at the age of 15 years, Valentin Serov had enrolled at the academy of arts in St. Petersburg, where he graduated in 1886.

“Girl with peaches” –

starting point of classical modernity in Russia

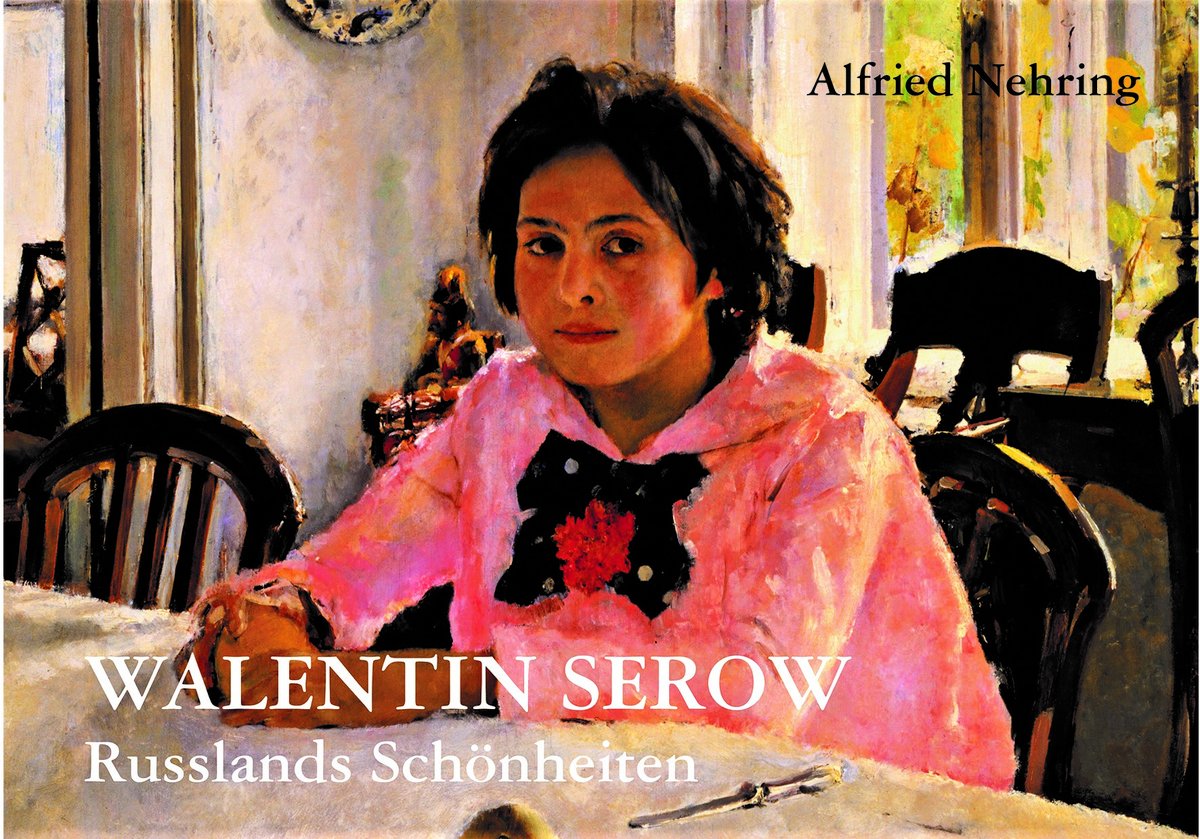

Back in Abramtsevo, the 22-year-old Valentin Serov sets his first exclamation mark: He meets the now 12-year-old Vera Mamontova. Almost a young lady by now, her charm and unsophistication enthrall him at once. He paints her portrait in oil and calls the first important piece of early Russian impressionist art “Girl with peaches”.2 A young girl in a bright pink blouse sits at a table and focuses directly upon the observer. In front of her there are peaches and a fruit knife. At the background there is a window with a view into the summer garden. This colour play and light composition had been unseen before in Russia: the blouse, highlighted by the sun, renders life and freshness to the painting, as well as the face of the twelve-year-old with reddish cheaks, dark, alert eyes and self-confident, earnest gaze and her youthful dark hair do – which is mirrored by her black tie with a red blossom. For days and weeks “Veruschka” had patiently modelled for the painter, her daily “reward” for sitting quietly were the peaches.

Valentin Serov gives the painting – “one of the pearls of Russian portrait painting”3 – to Yelizaveta Grigoryevna Mamontova, who had asked him for it, to thank for the pleasant and carefree time in Abramtsevo; it marks both the end of his years of apprenticeship which he had spent to a large degree at her place and also the beginning of a new period. In 1888 the “Girl with peaches” is on display in the periodic art exhibition of the Moscow Society of Art Lovers and makes Valentin Serov famous at once. Today it can be seen in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.

Marriage and breakthrough as a portrait painter

On invitation by his friend and former fellow student at the academy, Vladimir von Dervis, Serov lives and works for some time at his estate Domotkanovo near Moscow. By now he creates his artworks without commission, finds buyers for them and gets financially more and more independent. Predominantly he still paints portraits, of colleagues such as Ilya Repin and Isaak Levitan, of composers, opera singers and actors. In 1889 he and Olga Trubnikova, whom he had known since childhood, get married. The couple have six children, two of them are immortalised in the beautiful painting “Summertime”4. Almost the entire left half of the painting is dedicated to Olga, sitting in the foreground in the shadow of a wooden house. She wears a bright summer dress, on her head a big straw hat, adorned with a dark blue ribbon with a big loop. She looks at the observer and appears earnest but happy. The right half of the painting is all in green, the foreground is dominated by the dark green of a shadowy meadow getting ever brighter towards the background. There in the background the children are playing, behind them bright green birch trees in the sun. Among the paintings which Alfried Nehring includes and comments on in his book there are some very impressive examples of the “rural Serov”, in which the artist depicts the work-intensive reality of the life at the countryside.

Court portait painter for the Czar and his family

Serov is 23 years old, when a railroad accident (possibly yet another attempt to assassinate Czar Alexander II.) exerts notable influence on the course of his life: In October 1888 a train carrying the Imperial family from Crimea to St. Petersburg is derailed at high speed. 23 passengers loose their lives, miraculously neither the Czar nor one of his family are among them. This incident urges the Romanovs to have portraits painted of many of their family members, this prestigious commission is bestowed on Valentin Serov. He succeeds in creating many outstanding portraits, such as the portrait of the young Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna5, the portraits of Czar Alexander II. in the red coat of the Danish life guards6, the portraits of Grand Duke Alexandrovich Romanov with shiny golden cuirass in front of his horse7, the one of Czar Nikolai II.8 and many more. The young artist is not too comfortable mingling with these exalted circles whose way of life doesn’t mean a lot to him, but in any case he gets more famous: his paintings are well-known, estimated and even award-winning throughout Europe now.

In this time around 1899 the painting of his two sons Sasha and Yura9 is created during a vacation at the Gulf of Finland. Serov is fascinated by the “unsophistication and openness” of the two, which he regards as “precious gifts of childhood and of beauty in the life of human beings”10. This gets him back to the slogan which he had chosen for himself at the beginning of his career, namely the focus on “merry things” and “to paint only what is pleasant”.

Protest against the “Bloody Sunday of St. Petersburg” (1905)

Since 1897 Valentin Serov has been teaching at the Moscow academy of fine arts, graphic art and architecture. In 1899 he is elected to the council board of Tretyakov Gallery in St. Petersburg. A fixed income provides for the growing family.

However, the political development in Russia doesn’t allow Valentin Serov to stick to only nice and pleasant subjects for his art: On 22 January 1905 workers and farmers march to the winter palais in St. Petersburg to peacefully protest against the dismal conditions of their lives and to demand representation of the lower classes in parliament. Fire is opened on the demonstrators. Hundreds of them get killed, the day goes down in Russian history as “Bloody Sunday”. Valentin Serov becomes a witness when workers get shot even in front of the academy of arts. He feels sympathy for the writer Maxim Gorki whose portrait he had painted11 and who had been among the demonstrators, as a punishment Gorki is incarcerated in the Peter & Paul fortress for six weeks.

Serov draws a sarcastic caricature: in the foreground the Czar decorates soldiers who stand in file with medals, behind them the bodies of shot workers, while the Czarina in her carriage is driving across a graveyard. Another drawing is entitled “Harvest 1905” and shows a stubble field on which the pyramids don’t consist of grain sheafs but of bayonettes.12

The portrait as a characterisation

“The painter and his models” is the title Alfried Nehring gives to the last chapter of his documentation. It deals with the transition into the new century and into classical modernity. New techniques are explored, watercolours are tried out as well as distemper, one adventures into the area of nude painting.

In this phase the remarkable portrait of Henriette Hirschmann13 is painted, the wife of the Jewish art dealer Vladimir Hirschmann. The couple move constantly back and forth between Moscow and Paris. Valentin Serov shows the decadence of their way of life. No expense is too much, no detail is left un-stylised: the walls of the Boudoir are covered with grey linen, the model who is dressed all in black holds the white ermine fur with spread fingers to make sure the shiny precious stones on her rings catch the observer’s eye. She is standing next to a wardrobe made of Karelian birch wood, in the mirror one can get a glimpse of Serov’s face. The way he painted her face gave food for gossip: she focuses on the observer her gaze, is earnest with almost greyish teint as if her make-up was poor as someone commented. When the work was finished after one and a half years Serov receives letters in which people express their indignation about the way he allegedly had “disfigured, overaged and misread” Henriette Hirschmann14. The protesters can’t find any reemblance between the painting and the model. The latter, however, likes the result: she regards it as an artwork, “in which Serov succeeded to achieve his desired effects in a masterly way”.15

During a stay in Paris Serov attends a performance of the “Ballets Russes”. Like many others he gets to be intrigued by the extraordinary beauty and stage presence of the Jewish-Russian dancer Ida Rubenstein, whose style marks the end of 19th century ballet dancing. The two meet and she is willing to have her portrait painted by the famous Valentin Serov and also agrees that it will be a nude painting. Serov uses charcoal for the lining and distemper, namely Blue and Green only, for the body and and the background he uses the same bright Brown16. The portrait is not realistic but Serov morphes the dancer’s body into an “figure of art” with long lean limbs, which appears “overly slender and fragile”17. The head with the black curly hair is partially turned towards the observer whom she focuses upon, with an earnest and even sceptical gaze. In this oversized painting one can grasp the idea of what Serov’s intention had been in general when painting portraits: “As soon as a look at a human being carefully I am intrigued, yea even enthralled each time – not by the actual individual face, which may be plain, but by the charateristics it may assume on the canvas.”18

During the last year of his life he once again turned to a more traditional style of painting. At the age of only 46 years he dies from a heart attack in Moscow.

Alfried Nehring succeeds in a remarkable way to acquaint the reader with the private and artistic life of Valentin Serov, which unfolds in correspondence with the societal changes in Russia at this time, not the least he achieves that by showing many artworks from all periods of Serov’s life and explains their peculiarities to the observer. That way he gives a profound insight into the artistic development of this great Russian painter from an early stage to the peak of his expertise which has earned him an eternal place in the history of Russian painting and will continue to touch human beings for ever. The bibliophile illustrated book is bound in red cloth, the coloured book jacket shows the “Girl with Peaches». A table of content would have made orientation easier for the reader.

At the museum Frieder Burda in Baden-Baden (Germany) an exhibition with the title “Impressionism in Russia. Departure to avant-garde” will be on display from 1 March through 1 August 2021, including works of Valentin Serov19. From 28 August onwards it will be shown at the Museum Barberini in Potsdam.20 •

1 Nehring, Alfried. Walentin Serow, Russlands Schönheiten, Rostock (Klatschmohnverlag), Linen bd., 2021, 87 p., format 21 x 30 cm, 145 coloured illustrations, ISBN 978-3-941064-84-3, 24 Euro, to order: www.walentin-serow.de, p. 5..

2 ibid., p. 32, oil on canvas, 1887, 91 x 85 cm, State Tretyakov Gallery Moscow

3 ibid., p. 31

4 ibid., p. 48, oil on canvas, 1893, 60 x 49 cm, State Tretyakov Gallery Moscow

5 ibid., p. 56, oil on canvas, 1893, 60 x 49 cm, State Tretyakov Gallery Moscow

6 ibid., p. 57, oil on canvas, 1899, 170 x 117 cm, Collection of the King’s Life Guard in Kopenhagen

7 ibid., p. 58, oil on canvas, 1897, 167 x 50 cm, State Tretyakov Gallery Moscow

8 ibid., p. 62, Portrait of Nikolai II in the uniform of the Royal Scottish Guards Regiment, oil on canvas, 1900, 116x89 cm, Collection of the Edinburgh Regiment, and Portrait of Czar Nicholas II., Oil on canvas, 1900, 71 x 52 cm, State Tretyakov Gallery Moscow

9 ibid., p. 63, oil on canvas, 1899, 71 x 54 cm, State Russian Museum St. Petersburg

10 ibid.

11 ibid., p. 71, oil on canvas, 1905, 124 x 80 cm, Institut der Weltliteratur “Maxim Gorki” Moskau

12 ibid., p. 69

13 ibid., p. 75, tempera on canvas, 1907, 140 x 140 cm, State Tretyakov Gallery Moscow

14 ibid., p. 74

15 ibid.

16 ibid., p. 77, Portrait of Ida Rubinstein, tempera und charcoal on canvas, 1910, 147 x 233 cm, State Russian Museum

17 ibid., p. 76

18 ibid., p. 81

19 cf. https://artinwords.de/baden-baden-museum-frieder-burda-impressionismus-in-russland and Wikipedia under the keyword «Valentin Serov»

20 cf. https://www.museum-barberini.de/de/ausstellungen/591/impressionismus-in-russland-aufbruch-zur-avantgarde