A life for human rights, reconciliation and peace

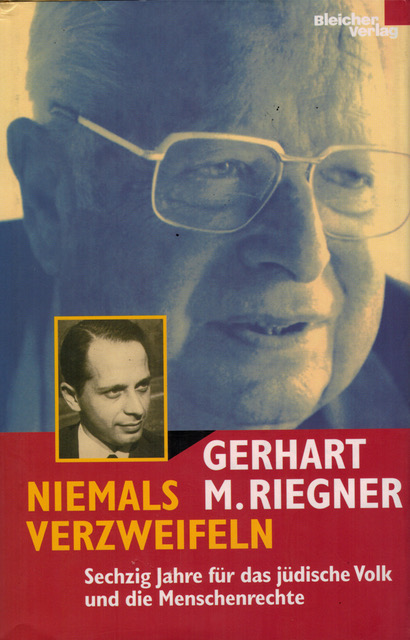

On the book “Niemals verzweifeln (Never despair)” by Gerhart Moritz Riegner

by Tobias Salander

Last year was the 20th anniversary of the death of Gerhart Moritz Riegner, a contemporary witness and contributor to the history of the 20th century. In an obituary the “Neue Zürcher Zeitung” paid tribute to him as a “warner and admonisher”. (https://www.nzz.ch/article7TYCU-1.506318).

Reason enough to take the autobiography entitled “Niemals verzweifeln – sechzig Jahre für das jüdische Volk und die Menschenrechte” (Never despair – sixty years for the Jewish people and human rights) and review some fateful events of the 20th century from the perspective of a contemporary witness. Riegner had received many awards and honours, including an honorary doctorate from the University of Lucerne, and was active for the World Jewish Congress (WJC) for over 60 years, many of those years as its Secretary General. He was the author of the famous “Riegner Telegram”, which in 1942 informed the Western powers about the mass murder of the Jews in Europe – unfortunately without being acknowledged. After the war, he was involved in the formulation of the UN Declaration of Human Rights and the later anti-discrimination declarations. It was also important to him to improve relations between Judaism and the Christian churches, and he played an active role in the creation of “Nostra aetate”, the declaration of the Second Vatican Council on the attitude of the Catholic Church to non-Christian religions of 1965. Not to be forgotten are his words of appreciation for the attitude of the vast majority of the Swiss population during World War II, which Riegner survived in Geneva, despite all the criticism.

Gerhart Riegner’s autobiography is a treasure trove for anyone interested in history and thus in their own origins. From the wealth of material, only a few points can be highlighted here, but they are suitable for contributing to a more differentiated picture of selected historical events. In addition to devastating events, Riegner also describes many positive and hopeful ones. It goes without saying that eyewitness statements, like other historical sources, must always be treated with due source-critical caution.

Riegner’s early assessment of Hitler confirmed by “crazy rabbi”

In 1936, Gerhart Moritz Riegner, born in Berlin in 1911, took over the management of the office of the World Jewish Congress (WJC) in Geneva. This had been founded in the same year to fight Hitler and to protect the Jewish minorities in Eastern Europe. At that time, the 25-year-old had been through difficult years, and much worse were to follow. Coming from an upper middle-class, cosmopolitan and highly educated Jewish family in Berlin, he took an early interest in the political affairs of the Weimar Republic. Already as a child, he became aware of his Jewishness through insults, and like so many, anti-Semitism threw him back to his roots. As early as 1933, it had been clear to the young law student, who had become a Zionist in 1930 “out of desperation”: In the German Reich under the rule of the National Socialists, Jews could not live in peace, freedom and security. He could not help but note the cowardice of the German intellectuals, which he could never forget. But a large part of his Jewish compatriots did not want to hear his warnings either and stayed – unfortunately too long – in Germany. They were encouraged in their attitude of repressing the impending disaster, according to Riegner, still full of consternation decades later, by a US rabbi whom Jewish organisations had sent from the USA to Germany to take a stand against another US rabbi, Stephen Samuel Wise, and to warn against him, because he was known as a “crazy rabbi”. But what had Wise, the ardent Zionist, honorary president of the American Jewish Congress and later co-founder and first president of the WJC, allegedly said that was so outlandish? Immediately after Hitler’s seizure of power, he had called for a boycott of Nazi Germany and warned that what was currently happening in Germany could happen tomorrow in any other country if it was not stopped: “It is not the German Jews who are being attacked. It is the Jews.” (https://www.worldjewishcongress.org/en/bio/rabbi-stephen-s-wise)

Riegner regrets that this crystal-clear assessment by Rabbi Wise in 1933 was so torpedoed by his own co-religionists. If Jewish organisations in the USA had failed, how could the masses have realised the seriousness of the situation?

Riegner’s flight took him first to Paris, then to Geneva in neutral Switzerland. And from here, for the next 60 years, he devoted all his energies to defending and protecting not only Jewish life worldwide. He saw the catastrophe approaching for the Jews and for world peace, but could not stop it – because of the moral indifference and political opportunism of a large number of people, but also states.

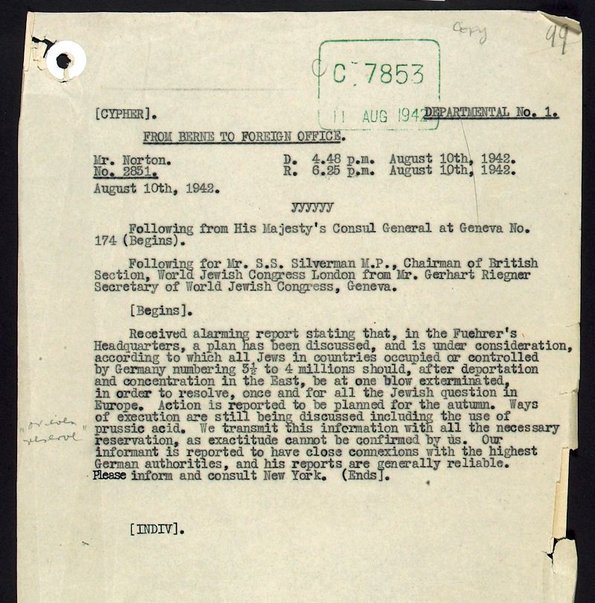

The Riegner Telegram reveals the “Final Solution”

On 29 July 1942, Benjamin Sagalowitz, press officer of the Swiss Federation of Israelite Communities in Zurich, called Riegner in Geneva to say that he had received information from a major German industrialist named Eduard Schulte, according to which Hitler was planning a mass murder of the Jews in Eastern Europe – with prussic acid. It took both of them a few days to really absorb this message. Of course, Riegner knew that on the anniversary of the seizure of power in 1939, Hitler had accused the Jews of warmongering and prophesied that this would lead to the end of the Jews in Europe, and he repeated this in 1940, 1941 and 1942. But was this to be taken at face value? Had “Mein Kampf” not been taken seriously? But there were the arrests and deportations of Jews all over Europe in the summer of 1942. And one knew the system of concentration camps in Germany. All this made the warning of the German industrialist seem credible.

Riegner also knew that horrific massacres of Jews had taken place after the invasion of the Soviet Union. And at the beginning of 1942 he had learned of killings by gas in buses. So Riegner confided in Paul Guggenheim, the legal adviser to the JWK and a Swiss law professor, with the aim of informing the USA and Great Britain. Subsequently, Riegner met with the US Vice Consul in Geneva. He asked him to inform the US government, to have the facts verified by the secret services and to inform the president of the WJC, said Stephen Samuel Wise, a personal friend of President Roosevelt. The telegram to be transmitted informed of the “Führer’s” plan to kill four million Jews in Eastern Europe and named as an unverified source the aforementioned German captain of industry with ties to the Nazi leadership.

The telegram went from the Vice Consul in Geneva to the US Embassy in Bern, from there to the US State Department in Washington. Riegner did the same at the British consulate. With the request that the telegram be sent to the British leader of the WJC, who should then inform Wise. This was wise foresight, because effectively the US State Department did not forward the telegram to Wise on the grounds that it was “unsubstantiated in nature”! Wise then received the telegram three weeks later, on 28 August 1942. He immediately informed Sumner Welles, the US Assistant Secretary of State, who did not want to publish anything until it had been verified by the Vatican and the ICRC. But they were unable to confirm the warning. In Great Britain, the relevant circles wondered who this Riegner was, because they did not want to believe his warning. According to Riegner, it is known today that the British secret service was able to crack the German radio code in 1941 and listen in on everything about the “Final Solution” decided in Wannsee in 1942.

Riegner was shocked by the tardiness of the Allies’ reactions. So, he collected further information: letters from Warsaw about the daily deportations, reports from Riga and the report of Swiss doctors who travelled to the Eastern Front and nursed German soldiers – against the explicit prohibition of the former Federal Military Department. The ICRC then also confirmed to Riegner that it had heard such reports from Germans. And the German industrialist who had first reported the plan for the “final solution” confirmed during another visit to Switzerland that Hitler had given the order for its implementation, which was then underway. Riegner passed on all this evidence to the US consul in Geneva.

In mid-October 1942, Riegner was finally invited to the US Embassy in Berne; he appeared with the representative of the Jewish Agency and presented a bundle of documents with statements from eyewitnesses. He also named the German industrialist Eduard Schulte. The ambassador considered everything credible, had some witnesses give an affidavit and sent the documents to the USA, where Deputy Secretary of State, Sumner Welles, confirmed to Stephen Wise that his fears were real. The WJC may now go public. This was done immediately by Wise and Nahum Goldmann, co-founder of the WJC and its president from 1951 to 1978, and the American and British Jewish organisations now put pressure on their governments to finally act. And eventually, on 17 December 1942, the governments of the USA, Great Britain and the USSR, together with numerous European governments in exile released a declaration, published in Washington, London and Moscow, against the Nazi extermination policy of the European Jews. It was reported about the deportations to Eastern Europe, but also about the mass murder in Poland and the system of forced labour. Those responsible would be held accountable after the war.

But the declaration turned out to be mere lip service. To the concrete proposals of the Jewish organisations how the Jews could be saved, the Allies replied that the first thing to do was the winning of the war. And the later request that the railway tracks to Auschwitz and the crematories should be bombed was rejected with the specious argument that the bombers did not have the reach – however, the IG Farben’s industrial plants at Auschwitz-Monowitz, five kilometres from Auschwitz, were taken under fire by the Allied bombers without any problems.

As a reader, one suffers with Riegner and the victims and is dismayed by the indolence of the Allies. Riegner asks himself the question why they failed and sees the reason in the widespread anti-Semitism especially among the Allies. The USA took in hardly any Jews, nor did the British, who also sealed off Palestine as a place of refuge. The US warships that transported material to Great Britain would have had no problem to take with them tens of thousands of Jewish refugees on their way back. The ransom of the 200,000 German Jews, which Nahum Goldmann considered in 1942, was rejected by the Allies – the war had to be won first, was the mantra from London and Washington.

In addition to anti-Semitism in the US State Department and the moral indifference of civilian bureaucrats and high-ranking military officers, Riegner identifies as a further cause for the failure of the rescue efforts the monstrosity of the crime, which was unprecedented and simply beyond the imaginable. Moreover, during World War I there was a lot of “fake news”, as one might say today, about alleged German atrocities, which were uncovered after the war. In addition, the Nazis carried out the “final solution” absolutely clandestine, and they also adapted the language to blur the facts.

And last but not least, Riegner emphasises that the Jews had hardly any influence on the politics at that time, a circumstance that, Riegner continues, is hardly imaginable today in view of Israel’s strength and the influence of the American Jews on politics.

A great disappointment for Riegner was also the Bermuda Conference of March 1943, where the British and the Americans met – with the Jewish organisations excluded – and decided in secrecy to do nothing for the Jews. The justification? First the war had to be won.

Is it any wonder that the notion that the Jews now needed their own state was achieving a majority among Jewish groups from 1943 on? David Ben Gurion had already expressed this in 1942: The objective of the Jews in this war had to be to attain a state of their own.

Cooperation of the WJC and the ICRC

Riegner and the WJC were already in frequent contact with the International Committee of the Red Cross regarding humanitarian aid during the Spanish Civil War. The then unsuccessful efforts of the ICRC in 1934 to expand the Geneva Conventions to also cover the protection of civilians in times of war were successfully supported by Riegner and the WJC after the war.

Towards the end of the war, Riegner succeeded in getting the ICRC, which he also subjected to massive criticism, to hold talks with the Nazis about the situation of the camp inmates. And actually, the Nazis granted the ICRC access to all the camps until the end of the war. This was an effective protection against the mass murder to be expected in the last months of the war. And on 21 April 1945 Himmler, who hoped for a separate peace with the Western powers, even received the envoy of the WJC, Norbert Masur, as well as Count Folke Bernadotte, the vice-president of the Swedish Red Cross. Hundreds of thousands were saved in this way, which, Riegner emphasises, is never written about in books about the Shoah; a fact that astonished him.

Switzerland saved more Jews than most other countries

It is strikingly remarkable that Riegner always takes his own point of view, nourished by his contemporaneity, usually far from any black-and-white portrayal or ideological narrow-mindedness. This is also the case when he focuses on his long-time host and country of refuge, Switzerland.

Riegner admits that despite all the sharp criticism on the Swiss authorities the geostrategic situation of the Swiss Confederation should not be left out of the equation when judging its role during World War II. From 1940 onwards, Switzerland was almost completely encircled by the Axis powers. Raw materials and food products had to be imported, and they were dependent on the goodwill of the Nazis. This was a very dangerous situation, and he himself had lived with a packed rucksack, so he could flee to the Swiss Alps at any time. As a contemporary witness, he took the military threat very seriously, unlike certain historians who judged in retrospect. That is why Riegner said that Switzerland had no other choice but to work for the German economy, otherwise there would have been mass unemployment, riots and an increase in the number of Swiss frontists. Here, too, Riegner clearly shows how difficult it was for Switzerland, they had no other choice! They had to constantly reckon with an invasion by the Wehrmacht.

Like many contemporaries, Riegner was offended by Federal Councillor Pilet-Golaz’s conformist speech, and like many others, he found General Henri Guisan’s Rütli speech a beneficial corrective. The majority of the Swiss seriously wanted to defend themselves. It was certain politicians who made concessions which the people would have rejected if they had known about it. Anyway, Riegner leaves little doubt about the Swiss population. In general, people did not appreciate Nazi propaganda. Of course, there were Swiss Nazi friends, the frontists, also in French-speaking Switzerland. But they never made up more than 10 per cent of the population. The closer people lived to the border, the stronger was the rejection of the German National Socialists and the Italian fascists! As far as the Swiss press is concerned, it had been a thorn in the side of the Nazis.

Regarding Switzerland’s official refugee policy, Riegner agrees entirely with the Bonjour Report, criticising the official refugee policy as too narrow-minded; much more would have been possible. But here, too, Riegner differentiates pleasantly when he distinguishes between the official policy and its often inconsistent enforcement.

In total, Switzerland had saved 28,500 Jews, more, and Riegner emphasises this specifically, than most other countries! Nevertheless, three times as many Jews could have been saved. After all, Switzerland had also hosted 100,000 soldiers.

As in all other countries, the Jews were not wanted in Switzerland – even among the Swiss Jews there had been restraint for a while. The Swiss Federation of Jewish Communities has been a member of the WJC. However, its president had distanced himself from the WJC during the war due to a misunderstanding of Swiss neutrality, and he was preferably on the side of the government and supported its restrictive refugee policy. After the war, he tried to justify himself to Riegner. His successor was then more courageous.

Even if Riegner states a deeply rooted anti-Semitism in Switzerland at the time, as in other countries, he acknowledges the resistance among the population against the harsh implementation of the refugee policy. During the war, a distinction was made between political and “racial refugees”. The latter had no right of asylum. Nevertheless, by 1942 another 1,200 Jews were accommodated in Switzerland as Riegner states.

On 13 August 1942, the so-called “racial refugees” were denied asylum. At least 30,000 to 40,000 Jews were rejected, into the hands of the Gestapo. It was known that they were being sent to certain death. Then there was an uprising from left to right against these harsh measures, which deeply impressed Riegner. Churches also criticised the government. The interventions caused a relaxation of the regulations. Children up to the age of 16 were now accommodated without restriction, including their parents; also, over 65 years old, sick people and pregnant women. And after Mussolini’s fall, Switzerland opened its doors wide to the Italian Jewish refugees!

Riegner gives Switzerland high marks for the reappraisal of its history and this before the Bergier Report. The Ludwig Report, for example, has come to terms with refugee policy very well. The nine-volume history of Swiss neutrality by Edgar Bonjour and the study by Jean-Claude Favez “The International Red Cross and the Third Reich” also have depicted history openly and honestly and led to the revision of refugee law.

Finally, in 1995, the then Federal President, Kaspar Villiger, admitted that one has incurred guilt towards the Jews. The police president of St. Gallen, Paul Grüninger was also rehabilitated in 1995. He allowed hundreds of Austrian Jewish refugees to enter Switzerland after the “annexation”.

Riegner’s commitment to human rights

A question that not only Riegner was bothering was how to prevent mass murders on this scale in the future. Struggling to answer the question of how to prevent genocide, the World Jewish Congress met in Atlantic City, New Jersey in 1944. The topic was once again the rescue of the European Jews. The delegates also called for the passage of a human rights declaration for the future, equal rights for all citizens in every country, the protection of minorities and that anti-Semitism has to be prosecuted in the future. Furthermore, the arrest of perpetrators since 1933, restitutions and collective reparations were demanded. Furthermore, the establishment of a secure home for the Jewish people in the British Mandate of Palestine.

Riegner and the WJC now also put all their energy into the formulation of human rights and the United Nations Charter. He points to the Ten Commandments and respect for the other human being, which could be considered as the Jewish roots of human rights. In general, one could say that the history of the Jews in modern times is the history of the struggle for human rights. Even though many countries have been reluctant to accept human rights because they perceived them as an intervention in their internal affairs, the WJC has explicitly supported that the international community could intervene if they were violated. At least five articles of the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights bear the impress of the WJC, such as Article 26 on the right of every human being to education and the right to attend school. Article 30, which says that one should not act against the Declaration and Article 29, which lays down that one should not act against the principles of the UN. Article 14 on the right of asylum, Article 7 on the prohibition of discrimination and Article 11 on the prohibition of retroactive laws has also been sharpened by the WJC. With the transition of the non-binding declaration into the two pacts on civil and political rights and on cultural, social and economic rights in 1966, it was possible to transform natural law into positive law.

After there had been a worldwide wave of anti-Semitic smear campaigns in 1959, Riegner and the WJC had become active, and in 1963 the anti-discrimination declaration on the basis of race/ethnicity was adopted, and in 1965 the convention.

The anti-discrimination declaration on the basis of religion or belief took longer. In 1981, the JWC under Riegner succeeded in adopting this together with the Vatican, who was concerned about Christians in Eastern Europe.

It was the merit of Riegner that in the 1990 Charter of Paris for a New Europe, paragraph 4 condemned racism and anti-Semitism.

The fact that the protection of human rights was also misused from the late nineties of the 20th century as a pretence for conducting wars of aggression against international law in order to enforce one's own power interests is not addressed in his book, which was first published in French in 1998. One would also have liked to know more about the relationship between Israel and the Palestinians. In his book, he only said that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s term has damaged the case of Israel and Judaism worldwide.

Riegner’s contribution to Christian-Jewish reconciliation

In search for the reasons for the crime of the Shoah, one must also closely examine the relationship between Christianity and Judaism. Even if the Nazi-friendly “German Christians,” who were racist, anti-Semitic and oriented to the Führer principle, insolently and foolishly declared that the Jew Jesus was an Aryan, the National Socialists were and remained clearly against the basic principles of Christianity, and their racial mania was diametrically opposed to the Christian conception that all human beings, in the image of God, belong to one family. Nevertheless, their biologic racial anti-Semitism was able to connect with centuries-old anti-Judaic resentments of Christian denominations. Starting with the late-authored polemics between the divergent groups of Christians and rabbinic Judaism reflected by passages in the New Testament, then with the Church Fathers of the third and fourth century, with St. Thomas Aquinas and innumerable councils: The contempt and disparagement of the Jews ran like a red thread through the history of Christianity. Again and again attempts were made to redefine the relationship of Christians to Jews, but only the serious and in-depth reflection on the Shoah brought a decisive breakthrough. Riegner’s contribution was essential in the attempts of the Catholic Church and the World Council of Churches, an ecumenical association of hundreds of Protestants, Reformed, Anglican and Orthodox churches, to redefine their relationship with Judaism. He freely admitted that he was able to take advantage of the rivalries among the various Christian denominations. Particularly in the case of the epochal break of the Catholic Church with its two thousand years old tradition of the “doctrine of contempt” (Jules Isaac) of the Jews, Riegner was there lobbying in the background. Beginning with the Council's declaration “Nostra aetate” of 1965, especially in its Chapter 4 on the relationship to Judaism, a rapprochement of the Catholic Church to Judaism began. Jews were no longer considered to be murderers of God, blind and hardened, rejected by God, and punished with the Diaspora, to whom God had revoked the old covenant. In several documents up to our present time, the Jews were described by the Catholics as “favoured and elder brothers,” according to Pope John Paul II, and “fathers in the faith,” according to Pope Benedict XVI, as worshippers of one and the same God of Israel. Finally, this also cleared the way for the recognition of the State of Israel by the Vatican in 1993, since Catholics no longer considered Jews to be in the Diaspora, since the accusation of the murder of God, as mentioned above, had already been rejected in 1965 with “Nostra aetate”. Riegner had played an essential role in this rapprochement and was officially invited to the solemn certification. Riegner, who died in 2001, still could witness the plea for forgiveness from Pope John Paul II in 2000 in Rome and Israel. This was also an initial reaction of liberal Jewish representatives to “Nostra aetate,” also in the year 2000; but this declaration was still sharply criticised by Jewish Orthodox circles. Riegner did not live to see, as of 2011, almost fifty years after the Council's declaration “Nostra aetate,” that Orthodox Jewish groups also turned to dialogue and thus reconciliation with the Vatican. They emphasised that, despite all irreconcilable differences concerning Jesus, the common ground should be put to the fore: the commitment to peace and social justice. Riegner would have been very happy about this, this reconciliation of people of different faiths was a matter close to his heart.

It is worthwhile to take the book in hand and go on a tour d’horizon through the 20th century. with all its disasters, but also with all its successful encounters of people of the most diverse provenance with the great goal of achieving more humanity. •

Literature:

Riegner, Gerhart. “Niemals verzweifeln – Sechzig Jahre für das jüdische Volk und die Menschenrechte.” (Never despair: sixty years for the Jewish people and human rights) Bleicher, Gerlingen 2001, ISBN 3-88350-669-9.

https://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_decl_19651028_nostra-aetate_en.html

https://icjs.org/dabru-emet-text/

http://www.imdialog.org/dokumente/jeru_rom_wortlaut.pdf