The path of an Israeli to Palestine

by Gabriela Wirth-Barben

Miko Peled lets the reader participate in his personal “path to Palestine” in a touching and stirring way.* His own story is closely interwoven with Israeli politics and the wars against the Palestinian people and the neighbouring Arab states, which he incorporates into his autobiography from a personal perspective. Already in his family and later during his service in the army the author learns to deal with the constant and increasing policy of injustice by the Israeli government, police and army against the Palestinian population. But it is not until his thirteen-year-old niece Smadar is killed by two Palestinian suicide bombers in 1997 that he decides to turn his life around: “Her death forced me to relentlessly examine my Zionist beliefs, the history of my country and the political situation that had motivated the suicide bombers who had killed her.” (p. 18)** Miko Peled establishes a relationship with fellow Palestinians at his home in California, learns of their painful experiences with the Israeli occupiers and is amazed at the warmth and hospitality they extend to him. Mutual trust is built up in a dialogue of equals, and the question of living together in peace, that moves everyone involved, germinates.

Role model of the parents

Miko Peled was born in Jerusalem in 1961, the fourth child of a “very well-known Zionist family” where politicians and generals came and went (p. 37). As a child, he was “impregnated with patriotism and belief in the Zionist cause” and urged to become “a hero and a great general like my father” (p. 63). However, in his family he also received a great deal of compassion. His father, Matti Peled, was “a great general” who was instrumental in the Israeli-Arab wars of 1948, 1956 and 1967, but over time he began to question much of what the Israeli army and state were doing to the Palestinians. In 1968, Miko's father resigned from the Israeli army, studied the Arabic language, became a professor of Arabic language and literature, and in 1973, together with Uri Avnery and other peace activists, founded the Israeli Council for Israeli-Palestinian Peace, which even then advocated direct talks between Israel and the PLO and the rights of the Palestinians.

Miko Peled describes his mother’s compassionate feelings and sense of justice with an impressive example. After the 1948 war, when the Israeli army offered her a beautiful house whose Palestinian owners had been expelled, she refused: “I should move into the house of a family that was perhaps living in a refugee camp? Another mother’s flat? Can you imagine how much they must miss their home?” She told this story many times to little Miko, adding that she was ashamed of the Israelis who left with looted carpets and furniture (p. 44).

Soldier in the Israeli

army and karate student

Like all young Israelis (men and women), Miko Peled was drafted into the army (IDF) at the age of 18 (1980) for more than two years of service. Although his father thought the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip was wrong by then, young Miko “as a staunch Zionist was nevertheless sure that Israel had to have an army”. He thought he could contribute to a “morally clean army” while protesting against the injustices committed by the IDF. The author relentlessly describes the brutal reality in a special operations unit, but thanks to a knee injury he was able to complete his training in a medical unit where he had time to “catch his breath and think things through carefully” (p. 111). He gave up the red beret of the elite combat troops and became an instructor for paramedics: “On the other hand, I liked the idea of teaching people how to save lives very much.” (S. 112)

Miko had already discovered his love for karate as a high school student: at that time he was “fascinated by the strict requirements of both karate and military combat training”. He adds, “But as I then found out, unlike the military [meaning the Israeli army], karate has a strong, uncompromising moral foundation.” (p. 121) Karate, “like all traditional martial arts, espouses a philosophy of compassion and non-violence” (p. 122). Miko Peled chose the non-violent path and trained as a karate teacher. After two years in London, where he married his girlfriend Gila, they moved to Tokyo. With his teacher there, the couple finally travelled to California in 1987, where they actually only intended to stay for two years, but they made their home there and started their family. In San Diego, Miko Peled opened his first dojo (karate studio).

Understanding

the point of view of the “other”

Very impressive are the consequences that Miko and some of his relatives drew after the death of his niece Smadar in a suicide bombing. His brother-in-law Rami, Smadar’s father, participated in the “Forum of Bereaved Families”, where Palestinian and Israeli families meet: “The message of the forum was simple: if parents who had lost their children could sit down and talk to each other, so could everyone else. There was a partner for peace, and peace was possible.” (p. 150) It was clear to the Peled family, however, that in addition to this personal level, it would also take a political reversal to make peaceful coexistence in Palestine possible. Miko’s sister Nurit, Smadar’s mother, according to the New York Times of 9 September 1997, called on the Israeli government to “stop the bloodbath” and accused the Netanyahu government of having “sacrificed our children for their megalomania – for their need to control, to oppress and to rule. [...] They want to kill the peace process and then blame the Arabs.” (p. 151)

The collapse of the Palestinian-Israeli peace process in 2000/2001 – brought about by the Israeli opponents of peace around Ariel Sharon, who was subsequently elected Prime Minister – and the death of his niece moved Miko Peled to take action. He learned about a Jewish-Palestinian dialogue group in San Diego and contacted it. At the first meeting, Miko (who was born and raised in Jerusalem!) thought: “This is the first time I am in a place where Jews and Palestinians are together as equals. [...] The fact that we could talk to each other here and look each other in the eye made a huge difference.” (p. 163) It was not easy for the son of a “successful” Israeli general to hear history from the Palestinian point of view: that Israel, for example, had not been the “David” defending itself against an Arab “Goliath” in the 1948 war (p. 167f). For Miko, “the only thing stronger than this myth was trust [...]. Without this trust, we would never have made progress. Our group was not about accusing each other, but about listening and telling personal stories.” This is how the Israeli learned that the Palestinians’ version of history was often diametral of what he had believed to be true.

The step to Palestine

Through his friendship with Nader, who had been expelled from Israel, and who, after 50 years in exile, finally received a passport with which he could travel to his hometown of Nazareth “at least as a tourist”! Miko Peled had the opportunity to visit him and his family there. Together with his wife Gila, he drove from Jerusalem to Nazareth in a car with Israeli number plates. He describes how he felt: “If someone had asked me if I was afraid of Arabs or of visiting an Arab city [...], I would have said, ‘No, of course not. Why should I?’ After all, I was an open-minded person, wasn’t I?” On his first trip to Palestine, he realised “how deep-rooted my fear really was” (p. 187). When they had to ask passers-by in Nazareth several times for directions to Nader’s uncle’s house, Miko and Gila felt very uncomfortable. Contrary to their prejudice, however, they noticed that many were eager to help them and made them feel welcome (p. 189).

After this experience, Miko wanted to get rid of his fear “once and for all. If there was ever to be peace, there had to be complete trust, and that can only be established by people at least stretching their hands over the wall of fear, if they cannot tear down the wall.” During his travels in the West Bank, Miko visited, among other places, a hospital for which he had organised a donation of wheelchairs with Nader and the Rotary Club of San Diego. In the process, he not only learned of the many unlawfully imprisoned and killed or wounded Palestinian men and women, but he also became acquainted with the abstruse Israeli security regulations that made it “impossible [to] contact the other side without breaking the law” (p. 191). Nevertheless, he stood in the way of the Israeli commanders, pointing out the “brutal, illegal occupation” they were trying to enforce.

It was even more difficult to get into the Gaza Strip and organise aid projects for the population there by the American Rotarians. The inhumane conditions in Gaza touched the author deeply: “The situation in Gaza is so bad that Israel’s rule over the West Bank looks almost like an idyll next to it. Israel’s restrictions on travel, movement and the import and export of goods, together with the occupying power’s complete control over land and sea, have created a state of siege that literally chokes off one and a half million people, including 800,000 children.” (p. 221f.)

“Peace between the Israelis

and the Palestinians is possible”

These are just a few of the many personal, historical and political insights in this powerful autobiography. The author dedicates the last chapter, “Hope for Peace”, to his youth. While conducting karate classes in Ramallah, he also spoke to the youth about the injustice of the occupation and encouraged them to find their way out of it without violence (p. 277). And he describes the heated discussions with his brother-in-law on the solution to the Middle East conflict that has been pending for decades: one state, two states, three states? (p. 310ff.) In the epilogue, Miko Peled impressively shows how far he has grown beyond his Zionist view through intensive relations with fellow Palestinians: “Today, I see my most important role in writing and speaking for – and actively participating in – the resistance against the Zionist regime in Palestine. Peace between the Israelis and the Palestinians is possible as soon as we move outside the paradigm of the Zionist state, a state that is wrongly called the ‘Jewish state’. [...] The Palestinians, the original inhabitants who were made victims of a colonialist settler state, are the rightful owners of the land. Acknowledging that this is the situation and that both Palestinians and Israelis must be able to live freely and in peace in a state that represents them both and where the same laws apply to all is, I believe, the first step. Until that is enforced, we have not solved any of the problems in Palestine.” (S. 326) •

* Peled, Miko. The General’s Son. Journey of an Israeli in Palestine. 2016

** The page numbers refer to the German version of the book; all quotes translated by Current Concerns.

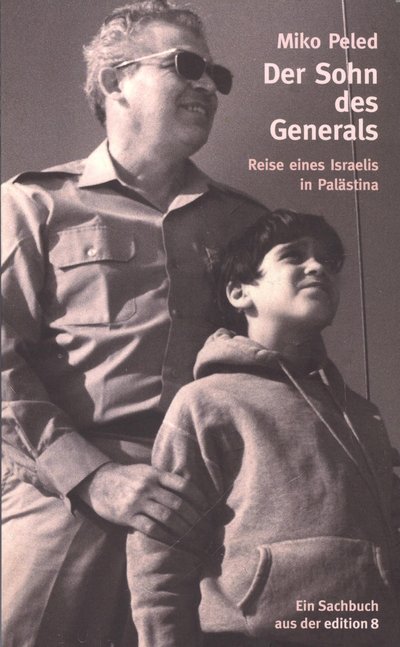

Bildunterschrift