“Hey Diddle Diddle, the cat and the fiddle …”*

Why language is more than just some language skills

by Dr Eliane Perret, psychologist and curative teacher

If young people have only a poor command of the German language after completing their schooling – especially in writing – this is not only a problem for the national economy and for future employers, as is rightly complained about today. The young people concerned are also restricted in their personal development and later life, and not only in their professional field of activity. In all other areas of life, too, it is important to be competent in language, to be able to express oneself in a differentiated manner, to understand the other person, to sensitively grasp the meaning of what is read and heard, and to effortlessly see-through sophisticated language manipulative techniques in advertising and politics. It is a developmental task on the way to becoming a self-determined, socially competent fellow human being.

“This is the thumb”

The language of every country is a work of art in which history, spiritual life and the respective conditions of nature are reflected and thus the heritage is passed on from generation to generation. For every child, language acquisition begins in the first years of life, always embedded in the network of relationships in its social environment: I was sitting in a doctor’s waiting room when I suddenly heard a mother and her child quietly reciting a verse. It was a finger verse, a funny language game in which each finger is assigned a sentence. The two of them were having a great time:

This is the thumb,

Which shakes the plums on the tree,

This one picks them all up,

This one carries them all home

And this little one here eats them all.1

After a few repetitions, the little girl knew the verse on her own and repeated it again and again. And then it was already time for the doctor’s visit.

Such finger verses – actually little stories – have a playful, humorous character and are characterised by sound painting, rhythm and catchy rhymes. They are integrated – and this is crucial – in the loving attention between the adult and the child, i.e., the cornerstone of a secure relationship.

“We are looking for old children’s verses …”

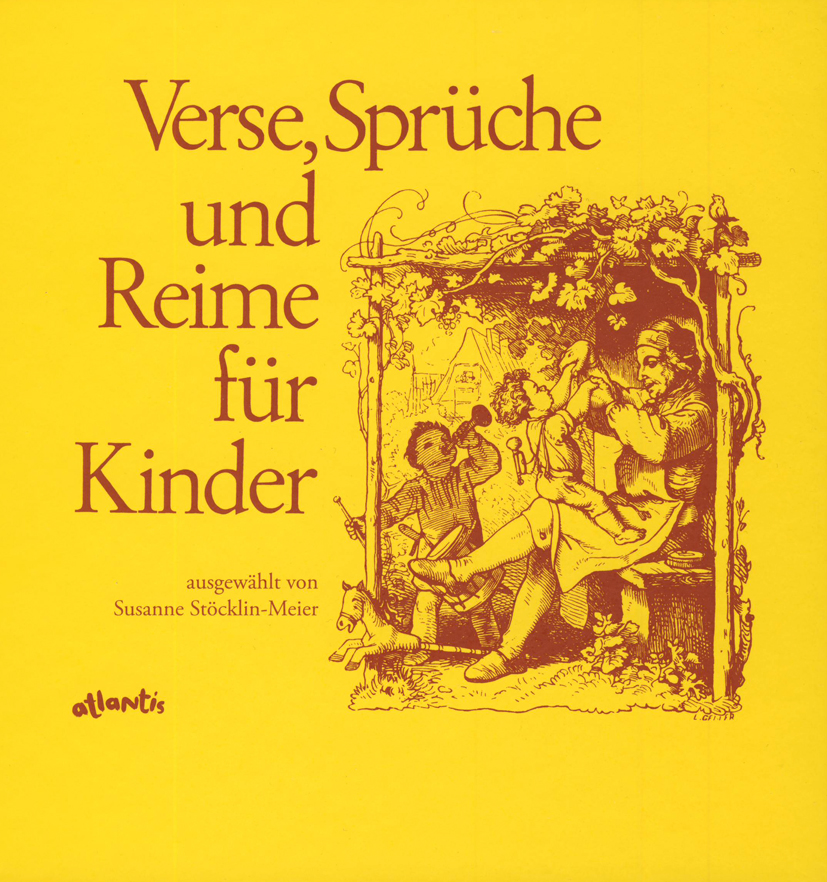

It was fifty years ago when a Swiss parents’ magazine launched a children’s verse competition with this appeal, asking parents and grandparents to send in verses, games and songs with which they entertained their young children. The result was a rich collection of familiar and less familiar verses in a wide variety of forms, a treasure that has been preserved from generation to generation. Susanne Stöcklin-Meier, a kindergarten teacher from the canton of Basel-Country, who had taken on this task, created verse sheets from the extremely rich and varied fund, which met with a lively response and ultimately led to her first book, which is unique in its kind and was in great demand. It has therefore been reprinted again and again until very recently and is still available in German.2

Language as a connecting element

When a child begins to formulate its first words and to call daddy, mummy, bow-wow and others by their names, it is met with enthusiastic goodwill by those around it. And rightly so, because in this way the child actively strengthens its “bridge to its fellow human being”, as Alfred Adler, the founder of individual psychology, described the meaning of language and described it as an important human achievement. It is a connecting element between people that has its roots in the first years of a child’s life. During this time, a child begins to collect words and sentences that enable him to formulate his thoughts, express feelings and desires, recount experiences and, in the process, engage in a back-and-forth with those around him. Scientists from the different perspectives of their fields have been dealing with this amazing process in the development of a child for a long time. Today it is clear that language acquisition is an important formative factor in the process of a child’s personality development. It takes place in the reciprocal relationship between the child and its fellow human beings and can never be replaced by a medium. “Language can only be practised and a vocabulary can only be acquired in a social environment where the child has connections and also takes up the connections”3, Alfred Adler already stated in the first half of the last century; a thesis that today is substantiated by developmental psychology and anthropological findings.

On the way to the ability to speak

In the course of their development, children gradually increase their vocabulary and expand their ability to express themselves. They learn to grasp the meaning of what is said and to echo it with an increasingly differentiated vocabulary. For what can be put into words becomes clearer, more understandable and more conscious. In interpersonal dialogue, thinking is stimulated and the children learn to process and structure their experiences so that they are available to them later in their memories. However, there is a long way to go from small verses to a mature ability to speak! The mother in the doctor’s waiting room had taken an important step towards this with her daughter.

“Hop, hop, rider”

Surely it is no coincidence that many adults remember verses and sayings that were common in their family. For example, when the father put the child on his knees and said ““Hop, hop, rider”; an affectionate question and answer game in which he let the child plop down carefully on his outstretched legs at the end – an amusing gives and take on both sides. Or as Stöcklin-Meier puts it: “This ‘cheap’ pleasure of being allowed to ride on father’s knee makes the smallest chap ‘rich’. Let us not deny our children this pleasure! Everything has its time. To dandle the child too. The feeling of security that this rocking triggers in the child cannot be made up for later.”4 Having such verses, rhymes and songs available for different situations is very valuable for parents and educators. They help to relax a situation, to give comfort or to express the common joy of what has been seen, heard or experienced. Susanne Stöcklin-Meier was rightly honoured by the Swiss Unesco Commission for her outstanding, lifelong achievement, stating: “For decades, Susanne Stöcklin-Meier has ensured that the intangible cultural heritage of the community ‘children’ is preserved and lives on.”5

With fun to language skills

Not only young children enjoy such language games. Often, they are connected with movements or serve as drawing aids, for example for a cat:

“Dot, dot, comma, dash, (face).

finished is the face, (head)

and two pointed ears,

so it is born. (belly)

Ritze, ratze, ritze, ratze (muzzle hair) – ready is the pussycat (tail)”.

Or have you also tried to say really quickly:

“Peter Piper picked a pack of pepper, where’s the pack of pepper Peter Piper picked?”

Many such “tongue twisters” also found their way into the aforementioned collection. We learnt these tongue twisters at school when we were ten years old and apparently practised it for so long that it still haunts my memory today. Or we would try to say our names backwards. And of course, the introductory ritual for a game of catch or hide-and-seek was always a counting rhyme with which we determined the starting child.

Not only cultural techniques

Obviously, the value of such games lies not only in stimulating children’s language skills (as we would say today), but also in strengthening the feeling of interpersonal solidarity. Because that is where these verses, rhymes and games came from, and that is where they are passed on and played! It is no coincidence that many of these verses, rhymes and sayings are spoken in dialect, the language in which a child feels emotionally “at home” and practices its mother tongue in many ways, an area of learning that is always underestimated. “By learning the mother tongue, the child acquires not only the words, their compounds and variations, but the infinite variety of concepts, conceptions about objects, the multiplicity of thoughts and feelings, artistic forms, the logic and philosophy of language – and he quickly and easily acquires in two or three years as much as he could not acquire half in twenty years of diligent and methodical learning,” wrote the Russian-Ukrainian educator and writer Konstantin Dmitrievich Ushinsky.6

For later learning success and learning to read and write, these linguistic forms of play are fundamental in the first years of life. This learning success begins with the acquisition of the mother tongue and is by no means exhausted by simple cultural techniques, because mastering the language is much more comprehensive. Ushinsky again: “In the language we find much deep philosophical spirit, truly poetic feeling, a distinguished, astonishingly sure taste, traces of a strongly concentrated thought, an immensity of unusually fine sense for the most delicate transitions in natural phenomena, great powers of observation, much strict logic, many noble spiritual impulses and germs of ideas, to which a great poet and profound philosopher would later only penetrate with difficulty [...].”7

Valuable cultural assets withheld?

These first language plays belong to the cultural assets of every people, just as they are found in literature, theatre, the fine arts, architecture and music. This cultural asset is always unique and must not give way to an all-levelling mass culture (a process that has unfortunately been going on for some time). It must be passed on to future generations and should be given a high priority in lessons and curricula. Of course, grammatical and orthographical tasks, exercises in style, etc. have their place in the language lessons of older children and young people. But we must not deprive them of the works created by poets and thinkers with high linguistic art. Who can remember “Nis Randers”, the dramatic ballad by Otto Ernst, which vividly depicts the dramatic rescue of a shipwrecked man, the humorously painted Sunday excursion “Mit dem Auto über Land” (In the car over land) by Erich Kästner or how Eduard Mörike quietly and poetically conjures up a spring mood with his poem “It is spring”? Knowing such works not only promotes rooting in one’s own culture, but it also strengthens social bonding and respect for what other peoples have achieved. Isn’t it a bit poor and an underestimation, even neglect of our upcoming generation, when in the Curriculum 21 for upper school students, under the search term “poem”, one of the competence levels to be achieved is limited to: “... can discover aesthetic design means in texts and describe them in German (for example, word play in a prose text, slang in a comic, rhyme in a poem)”? •

* The complete children’s poem reads: “Hey Diddle Diddle, The cat and the fiddle, The cow jumped over the moon. The little dog laughed,To see such fun, And the dish ran away with the spoon.”

1 “This is the thumb (pointing to the thumb),

Which shakes the plums (index finger),

This one picks them all up (middle finger),

This one carries them all home (ring finger),

and this little one here eats them all (little finger)!”

2 Stöcklin-Meier, Susanne. (1974). Verse, Sprüche und Reime für Kinder. (Verses, sayings and rhymes for children). Zurich: Wir Eltern-Verlag

3 Adler, Alfred. (1924). The Practice and Theory of Individual Psychology 2 – The soul of the difficult-to-educate schoolchild.

4 Stöcklin-Meier. (1974). p. 9

5 Address by Madeleine Viviani, Secretary General of the Swiss UNESCO Commission, quoted from Stoecklin-Meier, Susanne. (2009). p. 4

6 Ushinsky, Konstantin Dmitrievich. (1963). Die Muttersprache. Aus: Gesammelte Werke, BD. II. S. 554–574. In: Uschinski, Konstantin Dmitrievich. Ausgewählte Pädagogische Schriften. Berlin: Volk und Wissen, Volkseigener Verlag. S. 101 (The Mother Tongue. From: Collected Works, BD. II. pp. 554–574. In: Ushinsky, Konstantin Dmitrievich. Selected Pedagogical Writings) p. 101

7 Ushinsky, Konstantin Dmitrievich. (1963). p. 96

Susanne Stöcklin-Meier

ep. Susanne Stöcklin-Meier was born in Wangen an der Aare, Switzerland in 1940. She trained as a kindergarten teacher and later became known as a game educationalist and author of numerous other children’s books and radio and television programmes. Throughout her life she has collected rhymes, verses and games that at first glance seem trivial and irrelevant, but on closer inspection are a valuable cultural asset that would have been largely lost without her work. It is a cultural asset that is peculiar to each people and testifies their identity, into which a child must grow and, in this way, can also connect with people beyond the immediate family environment. Susanne-Stöcklin-Meier’s life’s work was honoured in 2008 by the Swiss UNESCO Commission as an outstanding, lifelong achievement. Today, at a more mature age, she is still active and passes on her knowledge with great commitment and enthusiasm on her YouTube channel and website: https://stoecklin-meier.ch/

Konstantin Dmitrievich Ushinsky

ep. Even though his name and work are little known in Europe, the Russian-Ukrainian educator Konstantin Dmitrievich Ushinski can certainly be ranked with the classics of pedagogy such as Comenius, Diesterweg, Froebel, Locke, Makarenko, Montessori, Pestalozzi, Rousseau and others. He was born in 1823 in Tula, a town south of Moscow, died in 1871 in Kiev and is considered one of the most important educators and founders of scientific pedagogy in Russia in the 19th century. He was also called the teacher of Russian teachers, the friend of Russian children, the founder of the Russian elementary school, the father of Russian scientific education and the promoter of equal education for women. On the basis of pedagogical anthropology, he wrote textbooks that were widely distributed. During a stay of several years in Western Europe, especially in Switzerland and Germany, he studied the educational system there and prepared a basic book on the significance of the mother tongue, which was subsequently reprinted again and again. He also wrote numerous children’s books. In addition to these practically oriented works, Ushinsky worked on a large theoretical work that had the human being as the subject of education as its theme. The first part appeared after his return to Russia in 1867, the second part was published two years later. The third part remained unfinished because Ushinsky died in 1871 as a result of an insidious illness.

Christian Friedrich Hebbel: «Autumn Picture»

This is an autumn day like none I have seen!

The air is still, as if one scarcely breathes,

And yet rustling, far and near,

The fairest fruits fall from every tree.

O disturb them not, Nature’s celebration!

This is the harvest she herself holds,

For today from the branches only loosens,

What falls from the sun’s mild ray.

(1852)

wp. Christian Friedrich Hebbel (1813–1863) was above all a dramatist of poetic realism who developed his own theory of drama and implemented it in his plays. In addition, he emerged as a lyric poet with his love poems, ballads and nature poems; the poem Autumn Picture is probably his most famous.