Promoting dialogue among civilisations

Reflections of a historian after a journey through Iran

by Dr phil. René Roca, Research Institute for Direct Democracy (www.fidd.ch)

Iran is currently in an extremely delicate political and economic situation. The unilateral and unjustified termination of the NPT (Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons) by the USA and the resulting tightening of sanctions are a catastrophe for the country. All this strengthens the radical forces in Iran, which reject further cooperation with the West.

Iran is an important regional power and, together with Russia and Turkey, has ended the Syrian war – at high material and human cost – thus preventing a second Libya. The USA played along in the end, but US foreign policy remains unpredictable. It is still unclear whether the USA will actually distance itself from the “new American century” (Project for the New American Century) declared before 9/11. Until recently, one of the initiators of the “new century”, John R. Bolton, was the National Security Advisor to President Trump.

The fact that the situation is as it is, is not due to Iran, but to the geopolitical interests of Western countries, which prefer to advance a dis-functional and destroyed Middle East rather than to cooperate constructively and peacefully with the countries. Iran has long been sending out positive signals and calling for dialogue on an equal footing.

UN Year of Dialogue among Civilisations

- In 2001, for example, the United Nations (UN) proclaimed the “Year of Dialogue among Civilisations”. Among other things, this was intended to formulate a counter position to the statements of the US political scientist Samuel P. Huntington. With his book, “Clash of civilizations and the remaking of world order” (original edition 1996), he hypothesised that in the 21st century there would be conflicts between different cultural areas, especially Western civilisation and the Chinese and Islamic cultural areas. The UN, on the other hand, wanted to focus consistently on dialogue: “For this reason, the Year of Dialogue among Civilizations pursues the goal of initiating a dialogue that – if possible – should both prevent and integrate conflicts.”1 The then UN Secretary General Kofi Annan appointed Giandomenico Picco as his personal representative for the UN Year. Picco was supposed to promote the discussion on diversity through conferences and seminars as well as the publication of information and school material. He had already served the United Nations for two decades and was best known for his participation in the UN’s efforts to negotiate the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan or the end of the war between Iran and Iraq. For this reason, Picco enjoyed special confidence in Iran. That was the reason why the dialogue among civilisations was also the subject of a round table at the United Nations headquarters in September 2000. The initiative was taken by the then President of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Mohammed Khatami. The round table, chaired by Unesco Director General Koichiro Matsuura, brought together the Heads of States and Governments and the Foreign Ministers of over 20 countries from different cultural backgrounds (among others Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, Sudan, India and also the USA): “All participants agreed that with the help of such a dialogue among civilizations, all nations would be able to replace enmity and confrontation with discussion and understanding.”2 The countries involved had high hopes that the next UN year would set things in motion. The goals for the year were the following:

- Opening the door to a great process of reconciliation in one or more parts of the world.

- Making diversity understandable as a step towards peace, where dialogue is a key to progress.

- Strengthening friendly relations among nations and eliminating threats to peace.

- Achieving international cooperation in resolving international problems of an economic, social, cultural and humanitarian character, and to promoting and encouraging respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all.

- Actively promoting a culture of peace and respecting one another, in all their diversity of belief, culture and language, neither fearing nor suppressing differences within and between societies but cherishing them as a precious asset of humanity.

- Emphasizing respect for the richness of all civilizations and to seek common ground among civilizations in order to address comprehensively common challenges facing humanity.

The year set many things in motion, peaceful dialogue was promoted, but then came September 11, 2001, and with it the attempt to realise the “Project for a New American Century.” The USA put Iran on the “axis of evil” and initiated its war policy with the devastating campaigns against Afghanistan and Iraq. It is thanks to Iran’s skilful policy and military preparedness that the country has not been destroyed yet. How apocalyptic a war would be (see Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya and Syria), one becomes aware when one travels through the country, admiring the cultural treasures in their grace and beauty and speaking with the open and hospitable people there.

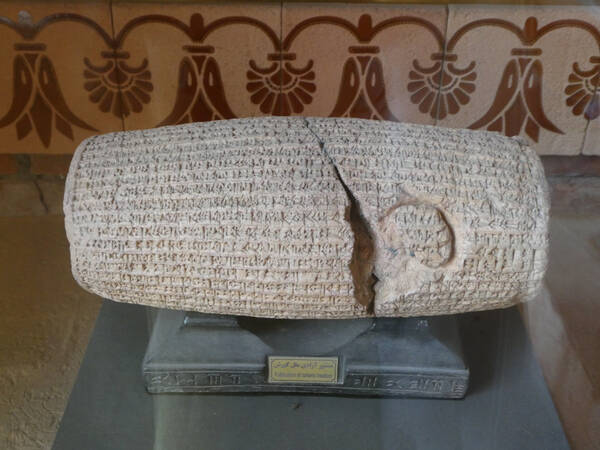

The rich history and culture of Iran/Persia

Ancient Persia is considered being the country of origin of human rights. In 539 BC the armies of Cyrus the Great, the first king of ancient Persia, conquered the city of Babylon. He liberated the slaves and declared all people have the right to choose their own religion. The Jews, too, are said to have been freed from Babylonian captivity by Cyrus. At the same time, he emphasised the equality of people in the world known at that time. These and other decrees, were recorded on a baked clay cylinder – the Kyros cylinder – officially recognised by the United Nations as the first human rights declaration, even though some Western historians question the text and dismiss it as propaganda. It is an unparalleled testimony to a tolerant attitude, which had not even developed by ancient Greece a hundred years later. This attitude was enshrined in the Zoroastrian religion that still exists today, which requires people to respect ethical values and encourages them to do “good”.

Even after the conquest by the Arabs and with the beginning of the Islamic period, the guiding line of equality and tolerance continued to exist. In Iran the Shiite Islam prevailed and with it also the importance of reason in the context of faith and the principle that everyone should form his own opinion. In short: If there is a dispute between two people, they must first seek dialogue, if they are unsuccessful, they must call in a third neutral party, and only at the end, if there is no agreement, the Koran must be consulted. This is a very pragmatic and human path, following the Islamic rationalistic theologian teachings (13th century) as well as natural law guidelines. The Egyptian Muhammad Abduh (1849–1905), one of the most important Islamic reformers of the 19th century and the founder of Islamic modernism, exerted a great influence by emphasising this pragmatism. He himself a follower of the colonialism-critical thinker Gamal ad-Din al-Afgani (1838–1897), Abduh relied on the argumentation of natural law, to be universally enshrined in human nature. National consciousness was also inherent in the nature of the human being, and therefore, a people who wanted to preserve its human dignity had to resist the degradation of Western colonialism and imperialism. Egypt, Iran and large parts of the Islamic world had then been subject to the domination and exploitation policies of Western countries. In Iran it was mainly the clergy who led the resistance against this policy.

Today, it can also be drawn on the tradition of natural law and human rights in Iran. Iran has a remarkable political structure, a mixture of theocracy and democracy. After some turmoil, the Islamic revolution of 1979, for the first time, a Western-oriented secular regime had been replaced with revolutionary means by a political order based on Islamism. This “Islamic turning point” in Iran can only be fully comprehended if one studies Iran’s history of the 19th and 20th centuries, under the influence of the colonial and post-colonial hegemony of the West. The Iranian way is an independent way and does not represent a theocratic “God state”, but – and this is shown by the political and economic reforms that have been forwarded again and again – an Islamic experiment that strives for a synthesis between traditional faith and globalised modernity together with the population.

Democracy is “not native” in the countries of the Islamic world, including Iran, as the recently deceased expert on Islam and author Arnold Hottinger writes3. However, Iran’s rich history and culture show important basic approaches and starting points, such as the Islamic Revolution of 1979. Hottinger adds: “The Islamic Republic unites in its constitution two contradictory basic principles, on the one hand popular sovereignty, expressed by the popular elections of the president and the parliamentarians, on the other hand theocracy, in the form of the absolute rule of the ruling scholar of God, appointed for life by a committee of high clergymen.”4 Looking at the European path to democracy, one sees how arduous and contradictory it was and is. Iran has already taken important steps towards more democracy. “Islamism”, according to Hottinger, “has contributed in many Muslim countries to the fact that the population began to see itself as the protagonists of political events, in many cases for the first time since the liberation struggle against the colonialists. For this reason, there is a possibility that the Islamist mobilisation could turn into a democratic one by some lucky chances. That the people, if they only know what they want, can advance the political process according to their will, would be one of the conceivable lessons drawn from the initial successes of Islamism, especially against the Shah of Iran.”5

Switzerland’s facilitation (formerly good offices)

The current visit of Federal Councillor Ueli Maurer to Saudi Arabia is very welcome. In addition to economic issues, he will also talk about Switzerland’s facilitation or mediation. Since the Islamic revolution, Switzerland has represented US interests in Iran and, conversely, Iranian interests in the USA. Saudi Arabia has now suggested a round of talks with the hostile Iran. Pakistan and Iraq want to mediate. It is to be hoped that Switzerland’s quiet diplomacy and the good will of the actors involved in the region will help to build the necessary trust and resume the path of “dialogue among civilizations”. It were desirable for Iran and the region to do so in the spirit of the Persian national poet Saadi, who wrote the following in the 13th century and whose lines adorn the entrance hall of the UN headquarters in New York:

Fellowship

Human beings are limbs of one body indeed;

For, they’re created of the same soul and seed.

When one limb is afflicted with pain,

Other limbs will feel the bane.

He who has no sympathy for human suffering,

Is not worthy of being called a human being.

This is a verse translation by Ali Salami6

1 www.unric.org. UN Year of Dialogue among Civilizations

2 ibid.

3 Hottinger, Arnold. Gottesstaaten und Machtpyramiden. Demokratie in der islamischen Welt. Zurich 2000, p. 11 (Theocracies and power pyramids in the Islamic World)

4 ibid., p. 402

5 ibid., p. 445

6 Gol-o-Bolbol (Rosen und Nachtigall). Ausgewählte Gedichte aus zwölf Jahrhunderten. übertragen aus dem Persischen von Purandocht Pirayech. Tehran 2017, p. 48 (Gol--Bobol (Roses and Nightingale). Selected poems from twelve centuries, adapted from Persian by Ali Salami.

(picture René Roca)