Search for traces in Syria: East of the Euphrates – Kobanê/Ain al-Arab

In early January 2020. The weather forecast was wrong. Rain was forecast in northern Syria, but bright sunshine breaks through the fog as the car leaves Aleppo early in the morning heading east. In a suburb Mohamed A., a Kurd from Afrin who grew up in Aleppo, is waiting. He speaks Kurdish and used to work as a cameraman and photographer for foreign media. He will accompany us for the next few days to the areas east of the Euphrates, still under Kurdish control – at least partly. Today we will go to Kobanê, also called Ain al-Arab.

Quickly Joseph, the driver, and Mohamed A. are engrossed in conversation, while my gaze glides over the fields that extend to the horizon right and left of the highway.

The large power station, heavily damaged during the war, is still not fully operational. It is stated that Chinese companies are working there, but the electricity for Aleppo and the surrounding area still comes from Hama via a power line that has been newly laid by China since the end of 2016. The large industrial city of Sheikh Najjar now has electricity 24 hours a day, seven days a week. In the city, public squares and streets are illuminated with solar panels.

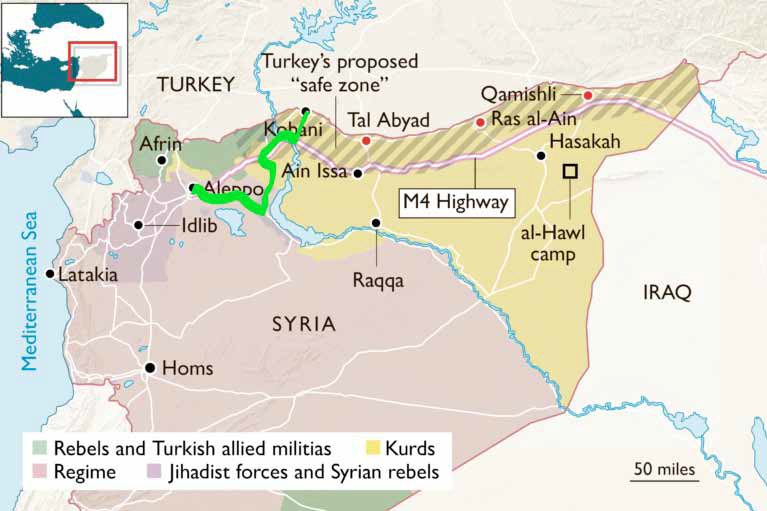

After the partial withdrawal of the Americans in October 2019 from areas east of the Euphrates, Russian and Syrian troops moved into their positions with short notice. Even before Turkey began its invasion, Syrian soldiers were again stationed in large parts along the Syrian-Turkish border and had hoisted the Syrian flag. Even though the journey to Hasakeh is currently too dangerous – since between Tall Abyad and Ras al-Ain fights are raging with the jihadists supported by Turkey – the way to Kobanê is open again. Finally I can cross the Euphrates again.

We drive from Aleppo on the motorway M5 in direction Rakka. At Mahdum we turn north and drive on a small country road through the villages towards Manbidsch. At a barrier we have to wait until an escort vehicle is assigned to us. The number plate is noted down, driver and escort have to identify themselves. My name is on their list anyway, my coming was registered. Then the turnpike is opened, the support vehicle drives in front of us. It has a different number plate, the letters MNB are followed by a number. “Welcome to the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria”, laughs Joseph.

About ten kilometres before Manbidsch we reach the transit road M4, leading from Aleppo via Al-Bab, Manbidsch to Tall Tamer, Qamishli and further on into northern Iraq to Mosul. This direct route between Aleppo and Manbidsch is closed to us because the triangular area between Al-Bab, Azaz and Djarabulus is controlled by Turkey and Islamist combat units – they call themselves the “Syrian National Army”. As if to confirm this, a Turkish mobile phone provider is calling in on the mobile phone. “Now we are on their radar,” says Joseph. As a Syrian of Armenian origin he has no sympathy for the Turkish government.

After a few kilometres, we turn onto the Arimah military base. I had been there two years ago. At that time the blue flag of the “Democratic Federation of Northern Syria” was flying next to the Russian flag. Now the flag of Syria is also flying next to these two flags. The Syrian army and the Kurdish People’s Defence Forces (YPG), who represent the Manbidsch Military Council here, share the available office space as brothers and sisters. Where two years ago, on the way to Manbidsch, I met a group of Kurdish military personnel, the head of the Syrian armed forces now resides. The large picture of Abdullah Öcalan, which hung there at the time and reached from floor to ceiling, has been replaced by a smaller portrait photo of the Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. The Kurdish official invites for a cup of tea, and soon afterwards, everyone is sitting together in front of the house in the sun, drinking tea and smoking. Water in plastic bottles is distributed. The bottling place is Zakho, in Kurdish northern Iraq.

The men’s conversation revolves around the Syrians who have fled to Germany. How many of them are there, do they want to know, and whether they behaved properly? What the German police are doing with the criminals and whether Germany does not want to send the Syrians back to Syria soon? “It is becoming more peaceful in Syria,” says one of the men. “We need our people back to rebuild the country.” “No one will come back,” replies another. “They’re fine there.”

The Euphrates

A little later we are again on the strategically important transit route M4 on the way to the Euphrates. We ignore Manbidsch, the former provincial metropolis and important for trade and smuggling between Turkey, Syria and Iraq. Car repair shops, parking spaces for construction vehicles, agricultural equipment and cars extend for kilometres along the outskirts of the city. Flocks of sheep are waiting for customers. Fruit, vegetables and used clothing are on offer. The men’s clothing identifies them as Arabs. They wear a long robe and a kufiya on their heads. Some have fixed the scarf with an agal, a black double cord, others have twisted the scarf into a turban. “Manbidsch is an agricultural centre,” Mohamed A. explains. During the war, the city became an important hub for the illegal oil trade between the oil fields occupied by Kurds and Americans in eastern Syria and customers in Turkey, Idlib and Damascus. “Syria buys back its own oil from the occupiers in the east, did you know that?” Mohamed A. asks. “It’s a shame!”

The road winds rising gently through a chain of hills. Then it goes down again, and in front of us, the wide blue ribbon of the Euphrates shines in the sun. Because of the heavy winter rains, the river is so wide that it looks like an inland sea. Islands protrude. Flocks of birds dance over the water. Far to the north and far to the south, one can see canyons the river has to squeeze through. The road leads over a narrow, partially damaged bridge to the east bank. Highly loaded trucks, minibuses, vans and cars push in both directions through the military checkpoint, which looks like a border crossing point. In the middle of the roof, which covers the checkpoint, flaunts the sign of the Asayesch, the Kurdish police special forces

The escort vehicle of the Manbidsch Military Council is replaced here by a heavy Toyota van that roars ahead of us. “Qassad”, Mohamed A. explains, “SDF, Syrian Democratic Forces.” The journey does not take long, and then the Toyota swerves. With difficulty, the driver brings the heavy car to a standstill at the side of the road. It is a puncture; a big nail sticks out the left back tyre.

Joseph offers his help and dismantles the flat tire with his tool. More is not possible. A special rod is missing. One of the Qassad companions makes a phone call and looks for a car mechanic. Together with Joseph, he drives away and returns shortly afterwards without having achieved anything. The car service station is closed. Finally, another Toyota stops and assists with the special rod that can be used to remove the heavy spare tyre stored inside the car. Finally, after an hour, the journey continues to Kobanê. We reach Kobanê around noon.

Kobanê – city of the martyrs

At the entrance to the town there is a large cemetery with a memorial made of steel and glass, which reminds one of a cathedral. It is the cemetery of the martyrs, explains Mohamed A., more than 1,200 men and women are buried here. The city centre is full of memories of the war. Posters everywhere remind us of the fallen. They show Abdullah Öcalan with fallen female fighters, fallen internationalists and even more of the city’s fallen daughters and sons.

At a central roundabout, the white statue of a woman is towering above the city. She is wearing the typical Kurdish clothes of the fighters with wide trousers and a uniform vest. Her hand stretches out into the sky, her wings grow from her shoulders. “This is our fighter Arin Mirkan,” explains a second Mohamed, who has meanwhile joined us in the car.

She was a highly revered martyr who opposed the IS troops and blew herself up. The statue was built by a team of artists in Suleymania and given to Kobanê as a memorial. Suleymania is located in the Kurdish autonomous regions in northern Iraq.

Like Mohamed A., Mohamed No. 2 also comes from Afrin. He is a doctor of the French language, studied in Aleppo. At the beginning of 2018 he fled from the Turkish troops and has been living in Kobanê since then. He works in the media office of the SDF and will accompany us through the city. “We are surprised that so few journalists from Syria come to us,” he says while driving through the city. “Most of them are from South Kurdistan.” This is what the Kurds call the three Kurdish autonomous provinces in Northern Iraq. The relations between the Syrian Kurds, the Northern Iraqi Kurds and the “Qandil Kurds”, as the Kurds of the Kurdistan Workers Party of Kurdistan, PKK, are called, are not free of tension. They are separated by different traditions and different political ideas. What currently holds them together in Syria is the alliance with the US-led anti-IS alliance.

Mohamed shows me the destroyed quarters of Kobanê, located directly on the border to Turkey. The ruins of the houses are untouched, children are playing, and men are searching the ruins for useful things. “The municipality plans to preserve the ruins and turn it into a museum,” Mohamed says. “So that the war and especially our fight for freedom will never be forgotten.”

The border crossing to Turkey is closed, the Turkish flag hangs limply on the mast. On the other side Turkey has built a wall. It is quiet, birds are chirping. Fresh green sprouts from the stacked sandbags. On this side of the border, the situation appears similar to that at the Arimeh military base.

The border crossing is controlled by the Syrian army, which has raised a Syrian flag clearly visible to the Turks. On the border building, which probably dates back to the time of the Ottoman Empire, there hangs a sign with the reference to “Rojava”. A Syrian flag is placed in front of it and the entrance below leads to the office of the Syrian army. The representatives of the Kurdish People’s Defence Forces keep away and watch. The SDF media representative Mohamed No. 2 joins with them for a chat.

The self-government after the Turkish invasion

Finally, we go to the mayor’s office to talk to the municipality. Lamis Abdallah is president of the administrative region of Kobanê, Tell Abyad and surrounding areas, Ain Issa and Suluk. She greets friendly, invites us to a warm place next to the stove. After I introduced myself and presented my questions, she hesitates and says that I had not registered. The questions were political and concerned the military, she would not answer them. SDF media representative Mohamed Nr. 2 tries to convince her to talk to the German journalist, but Ms. Abdallah leaves the room. When she returns a little later, she agrees to answer questions about the population, the health and labour market situation, education and housing. But how the situation for the administration of “Rojava” has changed after the partial withdrawal of US troops and the arrival of Russian and Syrian armed forces, whether there are conflicts, what future she sees for “Rojava” – she does not want to talk about that: “This is political and military”. And a photo? No, I cannot.

Lamis Abdallah is Armenian and comes from Tell Abyad. She tells us that when US soldiers withdrew in October 2019 and Turkey attacked, she fled through a humanitarian corridor. Their church in Tell Abyad had been converted into a military base by the Turkish occupying forces. Most of the Armenian families from Tell Abyad and neighbouring villages had fled directly to Aleppo. “From there they try to emigrate to Europe, Australia, Canada or the USA. Many have relatives there who help them. They will not come back.”

More than 150,000 people fled from the Turks, Ms. Abdallah continued: “They fled south, to Rakka, to a refugee camp.” The SDF administration had provided the people with mattresses and tarpaulins, otherwise there would be nothing. “The international aid agencies have left us.” In Kobanê alone more than 6,000 families would have found refuge. Each family is counted with five persons. According to Ms. Abdallah, doctors and professionals fled after the Turkish attack: “We have schools and hospitals in Kobanê, but we lack staff. The hospital in Tell Abyad is closed. The hospital in Ain Issa is very small and receives no international aid.

“Rojava” was the beginning of stability, says Lamis Abdallah. “We have rebuilt the society, the social relations. Women have equal rights in all areas of life. Turkey wants to prevent this; it does not want stability.” After the Turkish invasion, the situation had deteriorated considerably: “We lost most of our civilians. We receive no more international aid, no more food, no more assistance, nothing.”

Will it help to cooperate with the Syrian government in order to expel Turkey from the north-east of Syria? It is good that the Syrian army is again controlling the border with Turkey, says Lamis Abdallah cautiously. The UN Security Council must condemn Turkey, because the invasion is illegal. For Turkey, the Kurds are the most important target, adds SDF media representative Mohamed No. 2. The Kurds had organised themselves like a state, this self-government was a thorn in the side of all states in the region. Russia had made sure that after the withdrawal of US soldiers, Kurdish self-government would be maintained and had to be respected by the Syrian government. As agreed, the Kurdish fighters had withdrawn to positions about 30 kilometres south of the border.

Then Ms. Abdallah speaks again. The economic situation in Kobanê is stable. The monthly salaries are higher than in the rest of Syria, between 50,000 and 100,000 Syrian pounds (up to 80.00 euros). Heating oil is subsidised, refugees receive the heating oil free of charge. It was important to support the women, among them many were widows.

Joseph reminds us of the time. It’s early afternoon and the sun sets in three hours. Ahead of us is the road trip to Ain Issa. “Say hello to our friends there,” says Lamis Abdallah and accompanies us to the door. Perhaps a photo after all? No, she waves them off and smiles as she leaves. •

Source: deutsch.rt.com/der-nahe-osten/97786--spurensuche-in-syrien-2-ostlich/

(Translation Current Concerns)