Successful due to tradition

Successful due to tradition

by Dr phil René Roca*

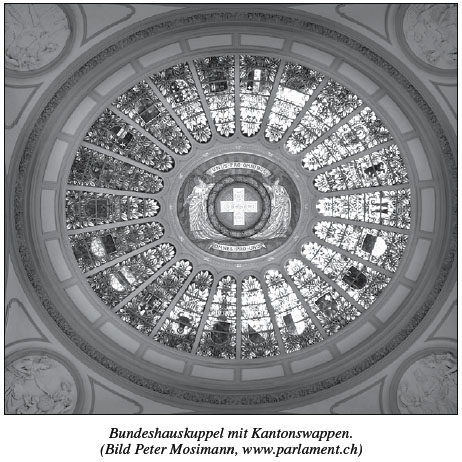

“Unus pro omnisbus, omnes pro uno” – this Latin dictum framing the Swiss crest adorns the dome of the Federal Palace in Berne. The maxim – “One for all, all for one” – refers to the corporate and social roots of the voluntary nation Switzerland. Cooperatives (“Genossenschaften”) in their diversity are still a pivotal fundament of the Swiss Federation. In the founding period of the Swiss Confederation (“Eidgenossenschaft”) – the term is evidence of it – the principle of cooperatives (“Genossenschaftsprinzip”) was already well known and trusted.

Anthropological fundamentals

The principle of cooperatives expresses in an anthropological way the social nature of man. Cooperatives were – and still are – born by a community that demands a high ethical requirement in each task and as an owner of a common cause assumes a lot of responsibility.

In this sense, cooperative forms of the communal life existed probably since the existence of humankind, but we often cannot prove it due to lacking sources. Within the geographical territory of Switzerland, cooperatives are attested since the early Middle Ages. These have always been locally rooted and decided democratically in assemblages about all arising questions; each member had one vote. The purpose of cooperatives always was for all members and the community the ideal exploitation of the common cause. The cooperative association did the work of the community. The rights and duties were put down in writing in statutes and so called “Talbüchern”. The ways of utilisation could differ, but it always had to answer the purpose of in natural law reasoned common good – the bonum commune. Switzerland in its tradition of the cooperative principle is not exceptional. According to the economist and Nobel Prize laureate Elinor Ostrom, varieties of cooperatives existed and still exist all over the world.

The origins in Switzerland

In Switzerland the so called “Markgenossenschaften” (marked cooperatives) also named “Allmende” (common land), gained in pivotal importance for the cooperative principle’s general spreading and shaping. “Allmende” was land that was parcelled for collective economical use. It had to be assessable as grass-, forest-, and badlands for everyone. Since the early Middle Ages the European nobility tried to rule or leastwise influence the “Allmendverfassung” (common land’s constitution). In many regions, so also the territory of present Switzerland, the cooperative principle could hold its ground. Due to the diversity of the local Swiss communities, numerous cooperative forms developed until the 18th century.

During the late Middle Ages and the early modern period, the village or valley cooperatives took on communal tasks which were beyond traditional activities. This was for example maintaining roads and bridges, or the water infrastructure, water supply, erection of church buildings or even the duty of caring for the poor. Thus, the village and valley cooperatives developed slowly into village and valley communities. Today not for no reason we say that the Swiss state was built bottom up.

Members of cooperatives were therefore village citizens and the recent village cooperatives developed into village communities, the so called “Bürgergemeinden” [collection of persons with citizenship linked to a particular community in Switzerland, editor’s note] which still exist in many cantons. From the late 18th century the commons were more and more divided. Some became single tenancy areas or were taken over by private hands, while others were claimed by municipalities, or there was a formation of private law corporations that partially still exist.

The cooperative movement in the 19th century

Based on the tradition of the commons and the diverse types of cooperatives, a broad cooperative movement established itself in Switzerland through the 19th century, especially as part of the increasing industrialisation.

This movement advanced into new, also industrial areas – in Switzerland and in Europe. Production cooperatives established in addition to the existing agricultural cooperatives. The idea of the production cooperative particularly results from the early socialist and social reform circles. They looked for an answer to the social question and alternatives to capitalism. Even the consumer cooperative and cooperative housing gained a great economic importance in this context.

Savings and lending banks existed in Switzerland since the first quarter of the 19th century as part of the industrial revolution. Home and factory workers in urban and rural areas wanted to invest their savings and arrange their pension plan. Since many savings and lending banks compromised their common public interest with risky dealings, they lost importance from 1860. A reasonable alternative were the emerging cantonal banks and the foundation of numerous cooperative local banks, among others the Raiffeisen banks. Thanks to larger capital base, they enjoyed greater freedom in credit accommodation and won the confidence of many citizens as cooperatives.

The cooperative movement of the 19th century laid stress on the cooperative roots in Switzerland. In this way a connection of conservative political forces with representatives of early socialist approaches succeeded. The education of citizens’ movements and popular movements, which put the cooperative principle on a cross-party basis into practice succeeded in this way as in the development of the direct democracy – starting from the communal level through the cantons up to the federal level.

Social capital and the third way – cooperatives in the 20th century

At the beginning of the 20th century, cooperatives in the services sector were added, for example in the electricity industry. The Migros, founded in 1925, was based upon an idea of Gottlieb

Duttweiler. In 1941, a transformation of the Migros into a cooperative took place. By that, the interests of the consumers should be preserved and the business practices should be oriented towards the “social capital”. Duttweiler’s idea of the social capital is based on the cooperative principle. The capital has to serve the community in a responsible sense and promote solidarity in society and democracy.

The cooperative principle gained many supporters not only as an economic concept. In the political arena personalities tried to establish this principle as the third way – beyond capitalism and Marxism. Thus, the labour movement in Switzerland took over the so-called “three pillars model” of “party, unions, and cooperatives”. The unions supported, among other things, the formation of production cooperatives and the Social Democratic Party (SPS) took the promotion of cooperatives into their programme from the beginning.

And today?

Studying the Swiss history and culture, the rich cooperative fundus is oblivious. We should increasingly ponder the three “selves” as a cooperative principle – the self-help, the self-administration, and the self-responsibility – in research and teaching, to give a meaningful ans-wer to current questions. Small and medium-sized cooperatives must get concrete support; administrative and legal barriers must not hamper their foundation. Big cooperatives of today should increasingly face the traditional cooperative principle and promote the participation of their members and not keep reducing it. •

* René Roca is a graduated historian, local council (independent, partyless) and teacher at a grammar school. He is founder and head of the Research Institute for Direct Democracy (<link http: www.fidd.ch>www.fidd.ch).

First publication in Raiffeisen-Panorama No 2/2016