The Raiffeisenbanks in Switzerland and the principle of cooperation

The Raiffeisenbanks in Switzerland and the principle of cooperation

by Dr phil René Roca*

For more than 20 years I have, with conviction, been a member of one of the 255 legally autonomous and cooperatively organised Raiffeisenbanks. However, lately, like many other members of the cooperative, I have been alarmed by certain developments in this cooperative bank. The Vincenz case, which I will not go into any further, is only symptomatic of these.

If you visit the website of my bank, the Raiffeisenbank Rohrdorferberg-Fislisbach, you come across a comic strip, well-made in terms of PR and in a prominent position, which advertises membership of the bank and concludes with the following motto: “Become co-owner of a bank, and determine how things are going to be.” The motto confirms an important guideline of the cooperative principle. If I want to become a member of a Raiffeisenbank, I buy a share and so become co-owner of the bank. At the annual general meeting, I have exactly one vote, regardless of whether I have one or more share certificates – according to the principle of “one person, one vote”. But the cooperative idea involves much more.

Mutual self-help as purpose?

If I look at the important article stating the purpose of my Raiffeisenbank in its articles of association, I come across the following sentence (Art. 2): “The bank conducts the following banking transactions in mutual self-help in the sense of the cooperative ideas of Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen [...].” What does this article of purpose mean? What does “mutual self-help” mean? What exactly do the “cooperative ideas of Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen” include? Article 5 of the articles of association further states that the bank is “a member of Raiffeisen Switzerland” and recognises its statutes. Raiffeisen Switzerland is itself organised as a cooperative. My bank, the Raiffeisenbank Rohrdorferberg-Fislisbach, is thus as it were a member of Raiffeisen Switzerland, which is based in St Gallen. If one studies Raiffeisen Switzerland’s statutes, the special article stating the purpose of the association (Article 3) is also remakable: “Raiffeisen Switzerland aims to propagate and reinforce the cooperative ideas of Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen in Switzerland [...]” Again, “mutual self-help” is mentioned, and the “cooperative ideas of Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen” are even to be propagated and reinforced.

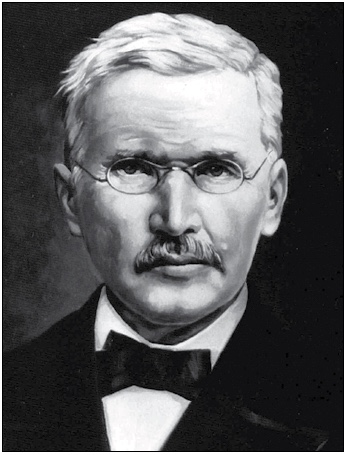

(1818–1888) (picture www.raiffeisen.ch)

Cooperative roots in the 19th century

At this point it is needful to take a short trip into history. As a mayor in his German hometown, Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen (1818-1888), whose 200th birthday we are celebrating this year, saw the hardships and worries of the farmers and traders of his time. Loans were only to be had with high interest rates and borrowers were soon caught in a debt trap. From what he saw, Raiffeisen drew the practical conclusion that the needy could only engage in the fight against usury and for fair credit in a joint alliance, true to the motto: “All for one and one for all”. The soon-to-be-founded “Aid Organisation” was “mutual self-help” in action, and the foundation stone for the first Raiffeisenbank. Raiffeisen assigned the task to serve as garantors for debts to richer fellow citizens. For example, farmers borrowed money to buy cows. They had to pay back the loan within five years. Their wealthy fellow citizens were liable for potential losses in solidarity and with their private assets. There was no dividend. Later, the borrowers became members, too, as they formed savings in good times, which could in turn be mortgaged. This form of capacity-building is a socio-ethical principle that belongs to the cooperative idea and has its roots in Christian charity, as Raiffeisen repeatedly emphasised.

The cooperative idea can be explained as resting on three terms combined with the word “self”: In addition to self-help these are self-responsibility and self-determination. The will to self-determination has a long tradition in the Swiss Confederation. Cooperatives in various forms have been attested in Switzerland since the late Middle Ages. That is why the idea of Raiffeisen fell on fertile ground especially in our country. In 1899, Father Johann Traber (1854-1930) founded the first Raiffeisenbank in Bichelsee. Since then, Bichelsee has been referred to as the “Raiffeisen Rütli of Switzerland”. Father Traber writes about the first Raiffeisenbank: “So the institution is really democratic and at the same time genuinely Christian; it is not money that governs here, but the moral value of the individual person.” The cooperative banks supported industrialisation in Switzerland sustainably and underpinned by democracy.

Apart from that, the cooperative principle and thus the demand for self-determination were an essential tradition in the 19th century, to first of all develop and then continuously expand direct democracy with the referendum and initiative first at the communal and cantonal level and finally also in the Swiss Confederation.

Considerations for securing and strengthening the cooperative principle

So what does this cooperative idea mean today? How can Raiffeisen’s ideas be propagated and reenforced, and how can the idea of “mutual self-assistance” be filled with new content? Here are three considerations to this effect:

- The current structure of Raiffeisen is centralised. The 255 autonomous cooperative banks are managed by St Gallen by means of a top-down strategy. This does not correspond to the cooperative idea. The basis, i.e. the cooperative members of each Raiffeisen bank, should decide by means of a decentralised (federal) structure, how things are going to be. The association must serve the individual banks, and not vice versa. That is how it was meant originally. The mergers of the Raiffeisenbanks were and are also wrong, leading to ever larger entities and less and less say.

- Raiffeisen Switzerland determines the strategy of the banking group, which is then approved by the delegates of the Raiffeisen banks. The delegates are organised in regional unions in the form of 21 associations (!). This structure is complex and above all undemocratic. As a member of the cooperative, I have never heard of these delegates at a general meeting or in any other way, so I do not know them and therefore cannot vote them in or out.

- The 1.9 million members of the cooperative must take the development of their Raiffeisenbank more strongly into their own hands again. First, they must call for the necessary transparency within the framework of the General Assembly, and then they must assert more influence concerning the strategic management of the bank, so that the actual cooperative idea can be reasserted; only then the cooperative idea can be spread and reinforced, which would be a blessing for the economy.

The Raiffeisen representatives are quite willing to talk, as I was able to convince myself personally. Now a broad discussion is to be conducted with the rank and file, i.e. the members of the cooperative, in order to secure cooperative co- and self-determination and to secure them for the 21st century. •

* René Roca has a doctorate in history and is a grammar school teacher. He heads the Research Institute for Direct Democracy (<link http: www.fidd.ch>www.fidd.ch).

(Translation Current Concerns)