A valuable cultural bridge

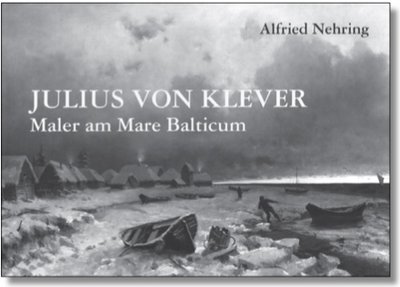

To the newly published art book “Julius von Klever - Maler am Mare Balticum” by Alfried Nehring

by Urs Knoblauch, cultural journalist, Switzerland

With the beautiful art volume “Abendglocken an der Wolga – Russische Künstlerkolonien um 1900” (“Evening Bells on the Volga – Russian Artist Colonies around 1900”), the theatre and art scholar Alfried Nehring not only impressively depicted the life and work of the world-famous Russian landscape painter Isaak Levitan (1860–1900), but also contributed to the tradition of good neighbourly relations between Germany, Russia and other European countries. (Current Concerns introduced the book in No. 11, 2017.) In his new art volume, the important Baltic-German-Russian landscape painter Julius von Klever (1850–1924) can now be discovered.

© Auktionshaus Neumeister München

Also with this artist the close relationship between Russia and Germany becomes apparent, as well as his openness towards Europe. In his life’s work his strong connection to the Baltic States, Germany and Russia are evident. He was one of the great Russian artists of Realism of the 19th century. He developed a style that was related to late Romanticism and in particular to Caspar David Friedrich. The study of nature was always in the centre: “The study is the artist’s most intimate dialogue with nature”, says Julius von Klever. The painter lived in Germany for many years and took part in major international art exhibitions. He was the best-known Russian painter in his lifetime in Germany and France and he was the darling of the Petersburg salons. In 1880 Julius von Klever was one of the first to exhibit at the then famous Paris Salon. He became famous with his Russian landscape motifs, which influenced his entire life’s work. Today his paintings are in great demand in numerous museums and on the art market, not only among Russian art collectors.

Biography as key to an artist’s life

Julius von Klever is born on 31 January 1850 in the tradition-rich university town of Dorpat, today Tartu in Estonia, as the son of a chemist and grows up multilingual. After graduating from grammar school, he studies at the Academy of Fine Arts in St. Petersburg. Following the family tradition, he bears the same first name as his father and passes it on to one of his sons.

Alfried Nehring vividly introduces the interesting family history: two years before the birth of Julius, “his father had earned a master’s degree after studying pharmacy. He wrote the required work in German. The 56-page treatise mainly dealt with the use of phosphorus as a fertilizer and was based on the research of the famous German agricultural scientist and chemist Justus von Liebig. Although the Klevers, like many German-Baltic families, have a title of nobility, he refrained from naming them in his master’s thesis. After passing the exam, the young scientist marries Maria Magdalena Gradek, who also comes from a German family. His hopes for a brilliant career at Dorpat University are not fulfilled. He only finds employment as a pharmacist at the Veterinary Institute. Four children are born in marriage” (Catalogue, p. 13), Julius with the second name Sergius is the eldest son along with two daughters and the youngest son. Family life is turbulent and full of joie de vivre. From the “hunting trips to which friends of his father like to take the nature-loving boy Julius Sergius, he often brings along drawings of woodland animals” (p. 13).

The author refers to the complex geographical and political conditions. For example, the “Livonian Government of Russia” is “of course administered from Riga, by a Russian governor appointed by the Tsar,” and the “judicial authorities, the military command and the police and county administrations are filled with Russian officials. Neither the Estonian nor the Latvian population is represented in the social upper class. Nonetheless, the various population groups live together peacefully and without conflict to a large extent.” (p. 13)

To the ruling Tsar family and the Romanov dynasty “the scientific and cultural potential of the German-Baltic families in Dorpat is worth quite a bit, and so [they] pour out ample medals and decorations. The pharmacist Klever is also “appointed State Councillor and Knight”, but nevertheless remains at the lowest level of the Veterinary Institute in his 40 years of work. In the last decade of the 19th century a “russification campaign of the tsarist government” was carried out in the governorate of Livonia. “In 1893 Dorpat was renamed Yuriev and had to use this name until the Estonian independence in 1918.

Russian becomes the sole official language. A ukase of the Tsar thus ends the liberal ‘Baltic relations’.” (p. 14)

These insights are intended to demonstrate how influential the family and cultural-political factors were for the further development of the young artist. Julius von Klever’s early interest in nature and in drawing and painting was vital for his life as an artist. Although, at the age of 17 in 1867, he intended to study art at St. Petersburg University, personal contact with his drawing teacher at grammar school, the well-known artist Konstantin von Kügelgen, was crucial. He was a friend of the family and court painter of the Romanovs and became his role model and promoter of his talent. As early as 1874 Julius von Klever became a founding member of the Petersburg Art Exhibition Society and received the first prize at the exhibition. Without graduation he finally advanced to become a member of the academy and professor in St. Petersburg. Nehring stresses the importance of this human relationship: “How important he was as an almost paternal mentor for Julius von Klever” is shown by the fact that Konstantin von Kügelgen also cultivated family ties from St. Petersburg. Julius von Klever himself then became a good fatherly mentor for the artistic education of his son Julius Juljewitsch Klever II. From 1908, he studied at the Academy of Arts in Munich and became a successful still life artist. He accompanied his father on his numerous journeys and nature studies. Unfortunately, he died “during the Leningrad blockade by the fascist Wehrmacht” (p. 42).

Against the background of these insights into the biography of the young painter, it is also understandable that the young artist Julius von Klever did not turn to the group and tradition of the Peredwischniki and their social revolutionary concerns around Ilya Repin. The travelling painters travelled from the cities to the countryside and paid tribute to the peasants and their environment in impressive pictures. Klever’s path to becoming an artist and to achieving his goals was formed early in his family, especially in the inspiring family relationships, in particular in the circles of the upper classes and under the influence of his teachers and supporters: “The sensational career that the young Klever had at the Academy in St. Petersburg was attributed by many of his fellow painters to the protection of Tsar Alexander II and the Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna. Nehring continues: “The Tsar’s sister was president of the Academy of Fine Arts in St. Petersburg. (p. 11) Famous art collector and patron Pavel Tretyakov also contributed to the artist’s success by purchasing a painting.

Landscapes of Realism in a magical atmosphere of light

Julius von Klever’s paintings are characterized by an extremely precise and at the same time poetic realism. His landscapes and his numerous sea paintings radiate a magical atmosphere of light. One is transported into romantically transfigured nature experiences and worlds of nature. In his beautiful woodland pictures, strong inner pictures and nature experiences from his own conception and the first drawing experiences in the mysterious forests are evident. According to Alexander Benois, director of the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, the paintings “seemed to exude such strong illusions that real scandals occurred at the exhibitions; visitors climbed over the partition wall to find out whether there was any deception behind this ‘miracle’ and whether the paintings were illuminated from behind with a transparent model. Some of them poked their fingers into the canvas, caressed them, looking for any kind of tricks. These daredevils had to be expelled with the help of the police.’” (p. 11)

Seductions of luxurious life and return to the meaning of life

The artist paints many pleasing paintings, sells well and in 1889 is invited by the Moscow multibillionaire Kuznetsov to paint a mural for the gallery in his summer palace in Foros (in Crimea), the “place of longing “of many artists in its Mediterranean beauty. Alfried Nehrung writes: “The luxurious life in the summer palace of Foros has something seductive about it and does not remain without influence on the further development of the painter”. (p. 53) The artist’s great success, his increasing wealth and prosperity, his restless travel and exhibition activities and the world of big money, seduce the painter to a dangerous lifestyle of passionate gambling, which leads him astray and into debt. He can free himself from these dangerous entanglements “and find his way back to his artistry and honest work”. He “leaves St. Petersburg, travels to Finland, lives for several years in Riga and Belarus, until he finally finds his way back to himself in Germany”. (p. 58) In 1990, in the “Petersburger Newspaper”, the artist impressively describes his “bad, lost years” in an open and honest way. “I stopped exploring nature, exploring it for new motifs.” “I had to decide whether I would surrender to the strong current, [...] as long as it was not too late already ...”

The artist dies on 24 December 1924 surrounded by his family and is buried next to his famous painting colleagues “at the Smolensk cemetery in St. Petersburg, the traditional burial site for professors of the Imperial Academy of Arts and St. Petersburg University” (p. 79).

The beautiful art volume, the first German-language work on Julius von Klever, should be widely distributed. The author writes: “My wife and I have visited St. Petersburg and Moscow several times in research for this book. We also followed the biographical traces of Julius von Klever in Estonia and Latvia. We will never forget the friendliness we experienced on these educational travels. To us, Europe does not end at the external border of the EU in the East. May this book be a small contribution to a better understanding and peaceful partnership”. (p. 84) •

The canvas hardcover book (Selbstverlag, ISBN 978-3-941-064-75-1) can be ordered for 24 Euro (without shipping costs) from the author Alfried Nehrig, Weg zum Hohen Ufer 21, D 18347 Ahrenshoop, Tel. 0049-38220-66189, e-mail: nehring.ag(at)t-online.de and post(at)julius-klever.com as well as via internet at www.julius-klever.com