How letterpress printing influenced the Zurich Reformation

How letterpress printing influenced the Zurich Reformation

Exhibition “Getruckt zu Zürich” – Letterpress and Reformation in Zurich

by Urs Knoblauch, culture journalist, Fruthwilen

On the occasion of the 500th anniversary of the Zurich Reformation and Huldrych Zwingli’s (1484–1531) inauguration of the parish office, numerous events will take place in 2019. A popular film is currently being shown in the cinemas, and numerous publications focus on the Zurich Reformation. An exhibition at the Central Library in Zurich shows that without the new medium of letterpress printing and the Zurich printer and publisher Christoph Froschauer (1490–1564) this revolutionary historical development would hardly have been possible. Until 30 April 2019, impressive exhibits will be on display in the exhibition room of the treasury. The exhibition was ceremoniously opened with a music programme, songs and psalms in the “Predigerkirche”. It shows how decisive knowledge, ethics and a thorough education are for cultural development and societal interaction. Especially in view of the increasing secularisation, the relativism of values, far-reaching technical and social upheavals, the question of the necessary transmission of moral and ethical basic values arises.

Printed scripts and bibles promoted the Reformation

In 1519, Huldrych Zwingli took up his parish office, began preaching the Gospel and developed an active reformatory ministry. During his only twelve years in office as pastor for the people at the “Grossmünster” in Zurich, he set in motion a fundamental change in church and society. The book printer Christoph Froschauer (1490–1564), who immigrated from Bavaria and was able to take over a printing house in Zurich through marriage, became an important collaborator of the Reformer. Zwingli and the book printer also played a leading role on the international stage, having great publicist influence on public opinion.

The Reformation also opened up a new major business area with numerous printing houses and book publishers. With almost 800 prints, the Zurich printer was one of the big names in the German-speaking world. Even after Zwingli’s death, the company continued to expand, made progress after Froschauer’s death, and was taken over by Orell, Füssli & Co. in 1798 after several changes of ownership. From 1780, Orell, Füssli & Co. also printed the prestigious “Zürcher Zeitung”, today’s “Neue Zürcher Zeitung”. In this context, the Landesmuseum is showing the exhibition “From the Bible to Bank Notes. Printing since 1519” from 21 February to 22 April.

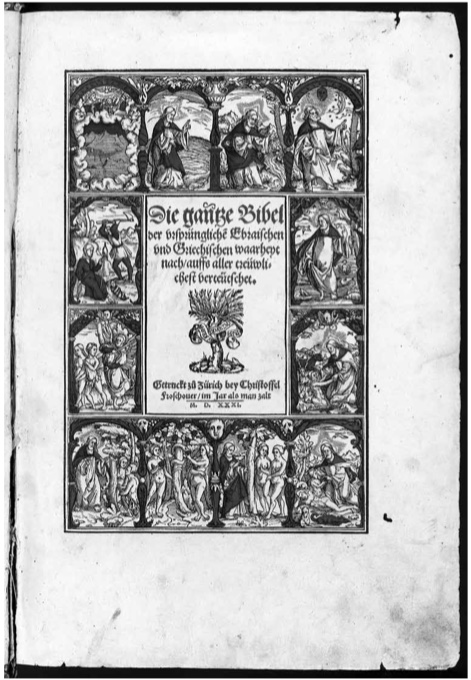

One of the great achievements of the Reformation was to make the Bible texts accessible through a generally comprehensible translation from Latin and Greek into German. Before the time of the printing press, various albeit little propagated translations existed already. In 1521 the New Testament of Martin Luther (1483–1546) was published in German, in 1534 the Old Testament followed. It was intended to make an important contribution to more “freedom for Christians,” according to Luther. Especially important, however, was Erasmus of Rotterdam’s (1466–1536) bilingual new edition of the Bible in Greek and Latin on which Luther’s translation was based. The great humanist Erasmus was a pioneer of humanistic popular education and a pioneer of coexistence in democracy and peace.

First schools in the monasteries

The reformers came from religious Catholic orders and universities. Especially in the monasteries, education and research was traditionally a central concern and the first schools emerged from there. In addition to agriculture, they maintained scritoriums where books were copied by hand and illuminated and manufactured with beautiful illustrations and pictures. In the monastery libraries, the books with the knowledge of the time were accessible to those who were literate. Renaissance scholars had already rediscovered and spread the treasures of the Orient. The Reformation contributed to further cultural development by making the Bible texts accessible.

With the Reformation and in the spirit of the early enlightenment, the need for schools and education for the population took centre stage. According to the Reformers, Protestants were to regard the Bible as God’s word, worship it and read the texts, especially in the families. The Bible was to become the only guideline for religious doctrines. “Sola scriptura”, this was one of the demands that contradicted the Roman Catholic papal church and its doctrine. Regarding the revolutionary spread of the Reformation, the illustrated pamphlets were decisive for the illiterate population. They clarified the contents of the Bible as well as the serious transgressions and the display of power of the Papal Church, the sale of indulgences and the Pope’s claim to authority.

Acces to the Bible for all people

Without the invention of letterpress printing with movable types, the phenomenal technical realisation and book production by Johannes Gutenberg (1400–1468) and the printing press developed by Froschauer’s pioneering work, the Reformation would not have been able to assert itself as quickly. Martin Luther, Huldrych Zwingli and numerous early enlightenment philosophers and reformers were concerned with translating the Latin and other foreign-language Bible texts into everyday language and thus making it accessible to everyone. Reading, however, had to be learned first. Thus, building schools became a central task for all. This led to the democratisation of education and the empowerment to help shape social institutions and the common good.

The destruction of the cultural assets of the Roman Catholic churches, the violence, murder and manslaughter of non-believers and heretics became a dark chapter of the revolutionary reformation movement. There were regional differences in the destruction of the churches and cultural assets. They were in the context of the power politics of the time, the personalities of the reformers, historical circumstances and the population. Thus, Erasmus of Rotterdam, who was in exchange with Martin Luther, with his reform concept tried a conciliatory way and a non-violent dialogue without iconoclasm and murder. The increasing violence of the Reformation, however, generated massive counter-violence. More far-reaching social demands and large peasant revolts arose which were crushed bloodily. The reformers usually took sides with the ruling political forces. This led to numerous religious secessions, such as the Anabaptists, who refused to follow Luther and Zwingli. For example, they practiced adult baptism and advanced social forms of living together. Until the beginning of the 20th century their civil disobedience was brutally crushed and suppressed, without entering into any dialogue.

Exhibits in the treasury of the Zurich Central Library

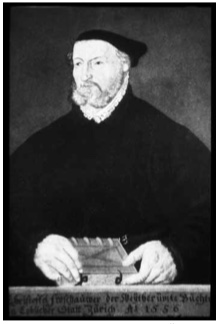

The exemplary exhibition distinctly illustrates the connection between letterpress printing and the reformation. The exhibition gives an insight into the range of publications of Offizin Froschauer, its iconographic design and implementation of the theological themes as well as the emerging censorship. On display are some unique and rarely presented documents such as Froschauer’s portrait from 1556, the Einsiedler-Codex used by Zwingli with handwritten remarks by the reformer, and Heinrich Bullinger’s coloured Reformation chronicle with a sheet on the “First Zurich Disputation” (1523). Scenes from the short feature film “Zwinglis Erbe” (Zwingli’s Heritage) (2018) will also be shown. The valuable objects, books, prints and paintings will be supplemented by the presentation of typographic and bookbinding techniques, tools and good explanatory texts.

Recollection on Christian tradition needed

The accompanying more than 400-pages publication “Buchdruck und Reformation in der Schweiz”, edited by Urs B. Leu and Christian Scheidegger, contains research contributions not only on Zurich, but also on Basel, Berne, Geneva, St. Gallen and Chur. Urs. B. Leu, for instance, reports in his interesting contribution “Reformation as a mission”, and that “the Zurich printer was regularly to be found at the Frankfurt Book Fair in spring and autumn and used to travel via Basel and Strasbourg”. Froschauer’s books helped “lay people to acquire basic theological knowledge and read the Bible”.

Especially today, a reflection on the roots of the Christian tradition and the European cultural substance is urgently in need. Libraries with a rich treasure of books refer to the question of the meaning of life, the unifying human values, a universal ethics and ways to peace on earth across cultures and religions. •

The exhibition is open Monday to Friday 1-5 p.m., Saturday 1-4 p.m. Diverse evening lectures. Free admission to guided tours and events. Information: Tel. +41 44 268 31 00 <link http: www.zb.uzb.ch>www.zb.uzb.ch