The Free State of the Three Confederations (Freistaat der Drei Bünde) – a democratic jewel

by Marianne and Werner Wüthrich

For every friend of direct democratic sovereign Switzerland, it was a treat to be present in Ilanz on 2 October 2021. The historical development of the unique model of the Canton of Graubünden and its contribution to direct democracy in Switzerland was presented in a scholarly synopsis to the 90 or so participants, who listened with rapt attention.1 The core of this model will be developed here from the presentations, in free reproduction.

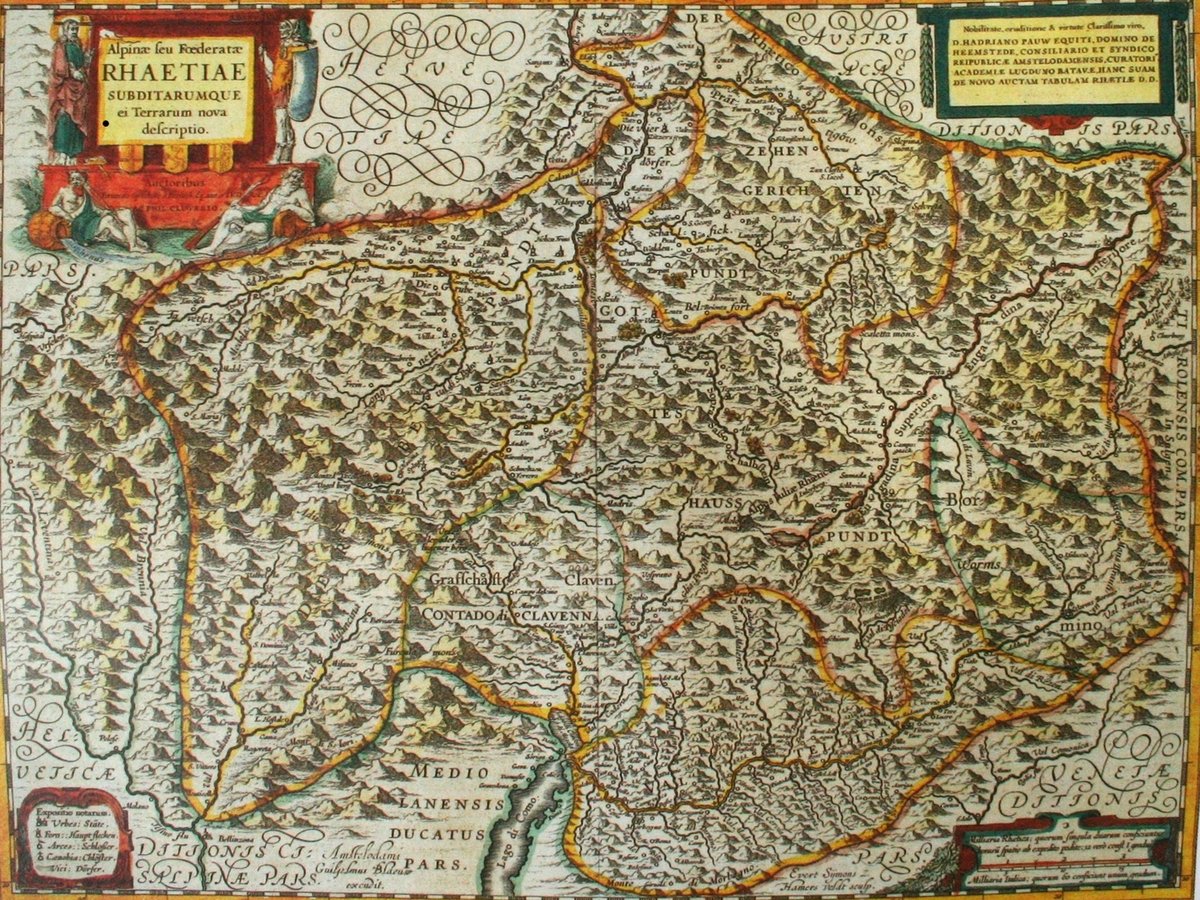

“Without an actively lived culture of peace, there can be no direct democracy.” These introductory words by René Roca opened minds and hearts to the history of the Free State of Graubünden (Grisons) with its three confederations (Gotteshausbund, Grauer Bund and Zehngerichtenbund) and to the unique democratic rights of the approximately 50 communes with judicial authority (Gerichtsgemeinden). These rights shaped the legal order and blueprints for lasting peace in these communes and in the entire State of the Three Confederations.

The mountain canton of Graubünden, with its 150 valleys and its 7,105 km2, is by far the largest canton in Switzerland (total area 41,285 km2). A Landsgemeinde (cantonal assembly), as other mountain cantons held them for the citizens of the entire canton, would therefore have been virtually impossible. Nevertheless, the people of Graubünden had organised their free state on a strong communal foundation since the 14th century (almost as early as the Swiss Confederates), and they had even put this down in writing in the Ilanz Letters of Articles (Artikelbriefe) of 1524 and 1526. Thus, it was possible to hold the triple federation state together through the storms of the Reformation and the Grisons turmoil –at the time of the Thirty Years’ War – until the occupation of Switzerland by Napoleon in 1798. A remarkable achievement! Until the time of the Helvetic Republic, the Free State of the Three Confederations was an associated state under Swiss Confederate influence; in 1803, Graubünden became a federal canton in Switzerland.

Sovereign communes with judicial authority determine their own destinies from the 16th century onwards

The Triple Federation was a loose confederation of states with a federal structure, first and foremost coordinating foreign policy and the joint administration of the subject territories. However, it was not the Bundstag (the federal diet) that “called the shots”, but the approximately 50 communes with judicial authority, for example Ilanz with twelve neighbourhoods (communes). They had sovereignty in all internal matters, but they also determined the policies of the Three Confederations in an original way – through the referendum. Much later, when laws were made subject to popular referendums in the cantons of St. Gallen and Lucerne in the 19th century, the Graubünden referendum law served as a model.

The fact that the villages in the valleys worked together early on to regulate their legal affairs on a democratic basis had its origins in the way they also worked together in other ways. For the management of their forests and alps, for the use of water and as mule packers for the transport of travellers and goods across the Alps, the people of Graubünden – like the people of Uri or Valais – had been uniting in cooperatives since the 13th/14th century. They were therefore used to solving together everyday issues as well as legal disagreements. They did this by means of “Mehren” (majority decisions) in the assemblies of the communes with judicial authority.

Other ethnic communities lived together in a similar way at that time. In the 19th century, the Graubünden democracy theorist Florian Gengel held that people’s rights, as they existed in the old Graubünden, were due to all peoples even without legal stipulation, because they had their basis in natural law, i.e. they belonged to them by nature. In Switzerland, the sovereignty of the people was the basis of all constitutions (Stefan G. Schmid).

The Graubünden referendum – a fascinating form of direct democracy

The old Graubünden referendum was the “real pivot of Graubünden democracy” (Florian Hitz). Decisions on domestic policy issues were, as mentioned, made sovereignly by the communes with judicial authority at their citizens’ assemblies. With regard to foreign policy (treaties with foreign countries) and the joint administration of the subject territories (Valtellina, Chiavenna, Bormio), the communes had a right of referendum, the results of which were coordinated in the Three Confederations. In the 17th/18th century, the right of referendum was extended to other areas. Decisions were made in the “Bundstag” (in Chur, Ilanz or Davos), to which the communes with judicial authority sent their messengers, or in the “Beitage” (adjunct assemblies), which met in smaller and changing compositions as needed.

And now we come to that feature which is special, one might almost say “revolutionary” – or rather evolutionary, which was developed without violence on cooperative, democratic ground: In the all-Federation decisions, “the communes with judicial authority played a more important role than the Bundstag” (Florian Hitz). Each messenger cast his vote (in larger communes two or three votes) in the Bundstag. In doing so, he had to follow the precise instructions given to him by his commune. If the messengers had no instructions on a question, no decision could be taken. Thus, the Council of the Federation functioned in a similar way to the Swiss Tagsatzung (executive and legislative council), where the envoys had to follow the instructions of their cantons and no decision could be taken in the event of major disagreement. In more difficult times, the “Bundstag” had to meet more frequently, in those cases the communes reported their answers to the referendum questions in writing.

The individual communes with judicial authority reached their responses by means of pluralities (Mehren). This could involve highly demanding questions, such as whether and which treaty should be concluded with Venice. Accordingly, the answers of the communes were often not limited to a yes or no; instead, the citizens discussed detailed contents and came to differentiated results. The Old Grisons referendum was also unique in its content: answers such as “perhaps”, “on condition that ...” or “yes, but ...” were possible. The heads of the Three Confederations had to sort out the diverse opinions and decide on this basis according to the will of the majority.

Through the demanding discussions and decision-making in the communes with judicial authority, the people of the Grisons were able to acquire a civic education and basic values long before the adoption of compulsory schooling in the 19th century (René Roca).

The “Bundstag” and the right of referendum of the communes with judicial authority existed until after the founding of the Swiss federal state in 1848, when it had to give way to the individual right to vote (Jon Matthieu). But even in today’s constitution of the Canton of Graubünden, the communes still have an optional right of referendum: according to Article 17, “1,500 voters or one tenth of the communes” can demand a referendum on resolutions of the Grand Council (cantonal parliament) on laws, intercantonal or international treaties or on major expenditure (financial referendum).

How the people of Graubünden coped with the difficult time of the Reformation

While in the 16th century, in the other countries of Europe the rule was “cuius regio, eius religio” – that is, the landlord determined the confession of his subjects, with a change of faith often being forced on people several times over, whenever there was a change of power – the Swiss solved this difficult task in different ways, not all of them democratic. The people of Appenzell, for example, divided themselves into a Catholic Innerrhoden and a Reformed Ausserrhoden, in some cantons there were Reformed and Catholic communes or parts of cantons, Central Switzerland remained Catholic, and in Bern, Geneva and Zurich the city councils determined the introduction of the Reformed faith (also for the rural population!) and closed the monasteries.

In Graubünden, too, there were secular noble families as well as bishops and abbots who wanted to impose their faith and their right on the population. But the citizens managed to elect their pastors and later also other officials themselves - in their usual way, i.e. by the “overruling” (“Übermehren”) of the feudal lords by the people (Randolph Head). This was not so easy, it was a tense time, but the people of Graubünden managed this democratically and thus in the long term preserved confessional peace.

Letters of Articles and Religious Dispute as the Foundation of the Free State

The Free State of the Three Confederations consolidated its statehood with the two Ilanz Letters of Articles (Artikelbriefe) of 1524 and 1526 – a statehood of its own kind (without common authorities). This laid the ground for confessional peace. The Articles determined the place of the churches in the Free State by granting the judicial communes the right to determine whether they wanted to remain Old Believers or to become Protestants. (Individual freedom of faith was not yet provided for at this time). In addition, in the “Gotteshausbund” they forbade the bishop of Chur and in the other two confederations all clergy from granting secular offices. The bishop was elected by the cathedral chapter – with the consent of the “Gotteshausbund”. Ecclesiastical abuses were to be put a stop to. For example: If a person, whether man or woman, is ill or dying, no clerical person, be it priest, monk or nun, may persuade the sick person to make a will without the rightful heirs being present. Apparently, ecclesiastical legacy hunting was a problem.

What was revolutionary was that land charges (levies, tithes) were to be reduced or even abolished. The Free State thus gradually became a country of free peasant landowners who had to pay only limited dues on their land. People agreed to “allow free trade”.

In 1526, the Ilanz Disputation took place. The Chur pastor Johannes Comander had written 18 Reformed theses (Disputationsthesen) and had them printed in Augsburg. (These were also to be the subject of the Bern Disputation a little later (1528). The abbot of St. Luzi, together with clergymen from the cathedral chapter, instigated legal action against Comander. The “Bundstag” scheduled religious discussions in Ilanz on the basis of Comander’s disputation theses. The result of the disputation was that he was not condemned; instead the Diet concluded that priests were to be allowed to “read mass or preach the word of God” (Jan-Andrea Bernhard). This conciliatory decision paved the way for the peaceful coexistence of the two confessions for centuries to come.

The Ilanz Articles heralded the coming of a new political and economic world in the Free State. The people in the communes ruled the Free State – and not the bishop or any lords. The Ilanz Articles were valid as national law until the end of the Free State in 1798. They set the direction for internal development and shaped the strong autonomy of Graubünden’s communes until today. •

1 The canton of Graubünden and its contribution to direct democracy in Switzerland. Dr. phil. René Roca at the 7th Academic Conference of the Research Institute for Direct Democracy FIdD.

Presentations by Dr phil. René Roca: “Der Kanton Graubünden und sein Beitrag für die direkte Demokratie in der Schweiz – ein Überblick” (The canton of Graubünden and its contribution to direct democracy in Switzerland – an overview); Professor Dr theol. Jan-Andrea Bernhard: “Kirche und Staat – die Wirkung der Ilanzer Artikelbriefe und Disputationsthesen” (Church and state – the impact of the Ilanz Article letters and disputation theses); Dr phil. Florian Hitz: “Das altbündnerische Referendum. Seine Praxis im Ancien Régime und seine Rezeption bei bündnerischen Rechtshistorikern der ersten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts” (The old-Grisons referendum. Its practice in the Ancien Régime and its reception by Grisons legal historians in the first half of the 20th century); Professor em. Dr Jon Mathieu: “Formen ‘demokratischer’ Politik im neuzeitlichen Graubünden” (Forms of ‘democratic’ politics in modern Grisons); Professor Dr iur. Stefan G. Schmid: “Florian Gengel (1834–1905) – ein Bündner Theoretiker der direkten Demokratie (Florian Gengel (1834–1905)” “A Grisons theorist of direct democracy)”; Professor Dr Randolph C. Head: “Gab es eine frühneuzeitliche Demokratie? Eine zeitgenössische Perspektive aus graubündnerischer Sicht” (Was there an early modern democracy? A contemporary perspective from the Graubünden point of view).

Conclusions reached on the occasion of the seventh academic conference of the Research Institute for Direct Democracy

- Since the late Middle Ages and early modern times, the canton of Graubünden has been a “laboratory” for the promotion of political participation and the development of democracy in Switzerland.

- The “old Grisons referendum” was, as a federal referendum, a central point of reference and model for the constitution of the legislative veto in the 19th century, i.e. modern direct democracy in Switzerland.

- The Swiss historian Adolf Gasser particularly emphasised the importance of “communal freedom” and, linked to this, the importance of the cooperative principle for Swiss history. European history, he said, was strongly marked by the contrast between two different attitudes, namely “domination and cooperation”.

The history of the canton of Graubünden is an impressive example of how the cooperative principle was successfully developed. Today, there is a danger that the cooperative principle “from the bottom up” will last no longer, but that the principle of domination “from the top down” will increasingly prevail.

Dr phil. René Roca