The German Greens want to come to power at any price

An Internet APO* is running for political influence

by Karl-Jürgen Müller

Who still remembers? On 18 May 2019, just before the elections to the EU Parliament, the YouTube platform posted a video by the German “influencer” Rezo on the internet. The title of the video was: “The destruction of the CDU”. For almost 55 minutes, the video sharply attacked the German governing parties CDU, CSU and SPD, as well as the AfD and the FDP. Rezo accused in particular the CDU and CSU for all sorts of things, not least a failure in climate policy. At the end of the video, he indirectly gave a recommendation to vote for Bündnis 90/Die Grünen.

The video was the most viewed YouTube video in Germany in 2019. By the day of the European elections in Germany on 26 May, it had been viewed more than 10 million times. In view of the losses of the SPD and CDU and the success of the Greens in the EU Parliament elections, the German TV station ZDF spoke at the time of a “Rezo effect”. An effect that was made possible also because Rezo was widely and favourably reported by the other media.

The Greens’ APO and not more democracy

Rezo is a young man presenting himself as an independent, alternative observer and commentator of political events. He appears determined and decidedly aggressive, assumes that the truth is on his side, and his choice of words and diction have nothing to do with a democratic discussion, but stage “rage” and “indignation”. However, every word, every gesture and facial expression is carefully rehearsed. Rezo has been well prepared.

With the “Rezo effect” at the latest, the power potential of the internet, especially when someone acts rudely, could have been generally realised. This is known from other contexts, for example the worldwide “colour revolutions”. This political power potential has nothing to do with the culture of dialogue, is in no way legitimised and its possibilities for manipulation go far beyond those of printed media. The pursued emotionalisation is evoking aggressive affects, not compassion.

Rezo, one can assume, is part of the extra-parliamentary opposition (APO) of today’s German Greens, who in public almost only pretend to be quite bourgeois. Rezo is not an isolated phenomenon. There is a system to all this. Public appearances like Rezo’s are on the increase. The target group is mainly young people. This has nothing to do with more democracy; at best, one must speak of an abuse of democratic rights.

“Rezo destroys COVID-19 politics”

On 5 April 2021 Rezo posted a new video on YouTube: “Rezo destroys COVID-19 politics”. As early as 12 am on 9 April, the video had more than 1 million views and more than 90 000 thumbs up, according to YouTube. The style of the video is similar to that of April 2019, but it is much shorter, lasting only 13 minutes. Key messages of the video are: From the beginning, the German government (here, however, Rezo limits himself entirely to CDU and CSU politicians) had totally failed in COVID-19 politics; CDU politicians had proven to be corrupt; scientific findings and scientists were ignored; in view of further “crises” (here he mentions the climate issue again) CDU and CSU were unacceptable. This new video was also received favourably by many other media.

Annalena Baerbock wants to become chancellor

On 19 April 2021, Annalena Baerbock and Robert Habeck, the two leaders of Bündnis 90/Die Grünen, told the public who the party should send as its candidate for chancellor in the upcoming federal elections (the date is 26 September). It is Annalena Baerbock. Since the last federal elections, the German Greens see themselves in a strong upswing. The results in the state elections since 2017 and the elections to the EU Parliament have strengthened the party’s belief that it can also gain power at the federal level. The only obstacles on the way to the chancellorship are the CDU and the CSU. They must now be weakened by all means.

As things stand today, it can be assumed that the federal government’s COVID-19 policy will be a central election campaign issue. In the meantime, it was possible to bring the polyphony and confusion over COVID-19 policy to a level that made many citizens lose their bearings. The poll figures for the governing parties, but especially for the CDU and CSU, are correspondingly bad. In the classic question of who they would vote for next Sunday if federal elections were held, the opinion research institute Forsa came up with a total of only 27 per cent for the CDU and CSU on 7 April 2021 and already 23 per cent for Bündnis 90/Die Grünen. As a reminder: In the 2017 federal elections, the CDU and CSU together had achieved almost 33 per cent of the vote and Bündnis 90/Die Grünen less than 9 per cent.

Why is no one asking about the political achievements of the Greens?

However, an answer to the question regarding the political achievements of the German Greens since 2017 is still missing. Moreover: this question is not even asked. However, being “green” is in line with the zeitgeist and pervades almost all political parties. Better formulated: All these parties have committed themselves to a “Great Reset” calling itself sustainable and a “Green New Deal” and want to be “green” today. And the German Greens have an easy time pretending to be the “original”.

In the process, they are putting up smoke screens. Or what are voters supposed to imagine in concrete terms when the party’s programme for the federal elections in September is entitled “Germany. Everything is possible”? These are word games with ambiguities familiar from psycho- and other manipulation techniques. Aren’t such word games distracting from the serious question of what a Green chancellor would really mean for Germany?

More war and less freedom

A few weeks ago, this newspaper1 argued that a foreign policy under Green leadership would drive Germany even more towards a US-oriented, ideologically coloured sharp confrontation with Russia and China. The danger of war would increase.

Isn’t it high time to take a closer look at what the German Greens are up to? The “Neue Zürcher Zeitung” of 31 March 2021 made a start – from their point of view. The title of the analysis was: “The Greens are all kinds of things – but not liberal”. The article deals with the above-mentioned election programme of the German Greens. The article formulates sentences that everyone in Germany should also look at more closely: “What would a Germany look like that was shaped according to the will of the Greens? The answer in the party programme is: It would be a quota-based republic with a demanding and allocating state permeating almost all areas.” “The Green state is a redistributive state.” “Diversity” is to be “lavishly subsidised”. The German Greens are about a “‘global socio-ecological transformation’ that knows only planetary boundaries”. “There is an abysmal imbalance in the Green core concern to ‘unburden us in everyday life’ through rules, laws and prohibitions: The Greens open the door to the tutelage of the state. They distrust the human being and fear his freedom.”

The article concludes with a question to pass on: “On the whole, the Greens are neither liberal nor bourgeois, but they are being elected by more and more bourgeois liberals. I wonder if the latter ever glanced at the guidelines the Greens want to use to regulate Germany, transform the economy and rebuild society.” •

* The APO, Extraparliamentary Opposition was a political protest movement in West Germany during the latter half of the 1960s and early 1970s, forming a central part of the German student movement. Its membership consisted mostly of young people disillusioned with the grand coalition (Grosse Koalition) of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the Christian Democratic Union (CDU). Since the coalition controlled 95 percent of the Bundestag, the APO provided a more effective outlet for student dissent. Its most prominent member and unofficial spokesman was Rudi Dutschke.

1 What will happen if Germany goes “green”? in: Current Concerns No. 1 of 20 January 2021

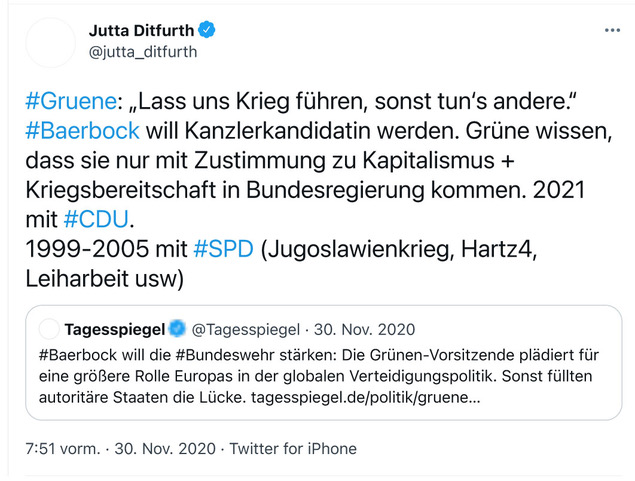

@jutta_ditfurth 30 November 2020

#Greens: “Let's wage war, or others will do it.”

#Baerbock wants to be candidate for chancellor. Greens know they can only get into federal government with approval for capitalism + readiness for war. 2021 with #CDU.

1999-2005 with #SPD (Yugoslavia war, Hartz4, temporary work etc.)

Quote of Tagesspiegel Tweet:

@Tagesspiegel of 30 November 2020

#Baerbock wants to strengthen the #Federal Armed Forces: The Green Party leader pleads for a greater role for Europe in global defense policy. Otherwise, authoritarian states would fill the gap.

https://tagesspiegel.de/politik/gruene...

Influencer in politics

ep. Influencers today not only play a crucial role in personalised advertising, but they are also increasingly influencing the shaping of public opinion and the balance of power in the political sphere. When using influencers, it is assumed that they have more impact than normal advertising, for example with celebrities. Influencers are more or less someone like you and me, nothing special, you can compare yourself to them and don’t have to feel inferior. In reality, however, they are set up and accompanied by cameramen, etc.

Barack Obama’s campaign team focused on individualised advertising using influencers in the 2012 US election campaign. By means of data analysis, every single voter was recorded and measured. From the beginning, Obama planned an vigorous outfit of volunteers to talk to as many voters as possible. Thanks to digitally created algorithms, the team knew who would be worth talking to. As a result, 21,000 volunteers knocked on 890,000 doors and had 350,000 conversations in the highly competitive state of Ohio alone in the last four days before the election. The volunteers had smartphones with them, with apps from which they could extract the exact wording of the opening or closing of the conversation for the respective person. The online advertising was also tailored to each voter in this campaign, achieving more impact than prime-time TV ads. Voters could be targeted individually through phone calls and social media.

In a sense, influencers take on the role of campaigners. They don’t knock on people’s doors, but report to them on their smartphones. Assuming that their followers identify strongly with their “stars”, this makes it much clearer to calculate which influencers should be considered as advertising ambassadors.

Source: Nymoen, Ole; Schmitt, Wolfgang M. Die Influencer. Die Ideologie der Werbekörper.

(The influencers. The ideology of the advertising bodies.) Berlin, Suhrkamp 2021

What the German Greens want in government

Excerpts from the election manifesto of Bündnis 90/ Die Grünen for the federal elections on 26 September 2021

“The transatlantic partnership remains a pillar of German foreign policy, but it must be renewed, framed in European terms, multilateral and oriented towards clear common values and democratic goals. As the core of a renewed EU transatlantic agenda, we propose to give a strong joint impetus to global climate policy, starting from the Paris climate goals. We are also committed to good cooperation with the US on digitalisation, strengthening multilateralism, trade issues and health. We want to work together for the global protection of human rights and a rules-based world order. This includes an understanding on how to deal with authoritarian states such as China and Russia. Even with the new US administration, the security policy focus of the USA will not again be primarily on Europe. The EU and its member states must adopt more foreign and security policy responsibility themselves. This applies in particular to the security of the EU’s eastern neighbours as well as the Baltic states and Poland. We want to conduct the transatlantic debate at many levels, including the respective federal and local ones, and thus create sustainable, diverse social networks. [...]

Russia has increasingly turned into an authoritarian state and is more and more aggressively undermining democracy and stability in the EU and in the common neighbourhood. At the same time, the democracy movement in Russia is strengthening. We want to support the courageous civil society that stands up to the increasingly harsh repression by the Kremlin and that is fighting for human rights, democracy and the rule of law, and we want to intensify the exchange with them. The EU has formulated clear conditions for easing the sanctions imposed on Russia because of the annexation of Crimea, which is against international law, and the military action against Ukraine. We will stick to these and tighten the sanctions if necessary. We are demanding that the Russian government implement their commitments under the Minsk Agreement. The Nord Stream 2 pipeline project is not only harmful in terms of climate and energy policy, but also in terms of geostrategy - especially for the situation in Ukraine - and must therefore be stopped.”

(Translation Current Concerns)