“Has China won? – China’s emergence as the new superpower”

by Dr rer. publ. Werner Wüthrich

At the end of last year, US President Biden convened a so-called “Summit for Democracy” with selected countries, including Taiwan. The Chinese government reacted sharply. It said that this summit showed a tendency of being a dangerous attempt to revive the “Cold War mentality”. Likewise, the USA, Canada and Australia announced that they would not send any political representatives to the Winter Olympics in Beijing in February. In response, China published the white paper “China: Democracy That Works” with the following key message: The Communist Party CCP does have the monopoly of power (with the main task of holding together the giant country with its 1.4 billion inhabitants). But in the municipalities, counties, cities, in the numerous autonomous areas, in the numerous People’s Congresses with their committees, every single citizen has a multitude of opportunities (and these are used) to get involved, to have a say, to elect their authorities and to have a say in factual issues. Ideas and suggestions are collected and are incorporated in the authorities’ decisions. On this basis, the government can make sensible decisions and the country remains stable. – To the USA accusations, China responded with the US-critical paper “The State of Democracy in the USA” (Radio China International of 4 and 5 December 2021). – This is likely to kick off a major global debate on democracy. – I certainly hope so.

The book by Kishore Mahbubani “Has China Won? – The Chinese Challenge to American Primacy” excellently explains the background of the renewed, dangerous escalation in the relationship between China and the USA. China has experienced tremendous economic development in the last 30 years and has brought around 800 million of its citizens out of extreme poverty. It has produced millions of entrepreneurs. Thousands of new companies are founded every year, supplying the world with high-quality goods. – None of this can happen without freedom. A large middle class has emerged, so that today the country lives in modest prosperity. Surprisingly, however, the newspapers in the West and especially in the USA are full of comments critical of China and one-sided negative articles. (see p. 174)

Kishore Mahbubani mentions as an example in his book the speech by US Vice President Mike Pence on 4 October 2018, which he devoted to China. It represented a new low in the US-China relationship. Mahbubani: “It was a nasty, condescending speech, one that none of his recent predecessors would have delivered.” (p. 257) He states, “Given the poisoned atmosphere toward China, it would be unwise for any American politician or public intellectual to advocate more reasonable approaches towards China.” (p. 254) Mahbubani compares the situation to the Cold War in the 1950s.

Kishore Mahbubani takes a different view on many things. His book “Has China Won? – The Chinese Challenge to American Primacy” was published in German a few weeks ago. In view of the China-critical staccato in the Western media, his book is valuable as a counter-position. It encourages the reader not to be satisfied with the one-sided view dominating politics and the media, but to also look at the other side of the coin. My book review will therefore differ from a “normal” book review. I will take the main points of Western criticism of China as a starting point and contrast them mainly with some verbatim text passages from Mahbubani’s book. (The page numbers in the text refer to the English version of this book. For a few quotes no page numbers can be given, since they are taken from the German edition).

This much in advance: the widespread hope in the West that, with its economic development and opening-up, China would also approach the USA and the West politically has proved to be false. According to Mahbubani, Asia’s economic rise means that other nations must learn to accept different social and political systems in order to avoid major conflicts.

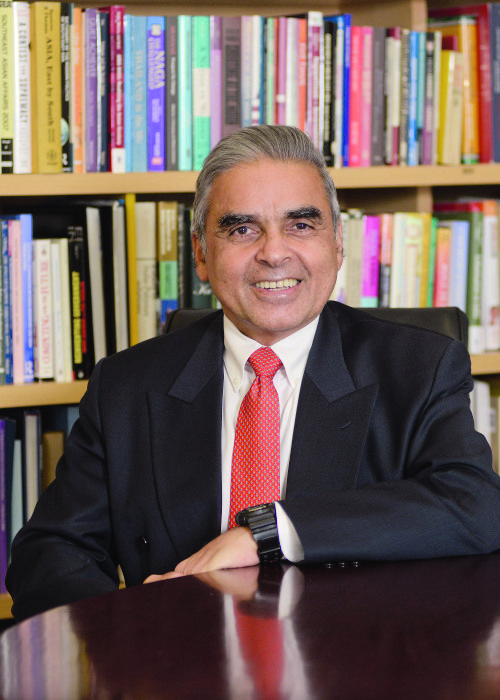

But first a few words about the author Kishore Mahbubani: He grew up in Singapore. His family has Indian roots. “My mother would take me to pray in Buddhist temples as well as Hindu temples, when I was young.” (p. 13) Mahbubani served in the Singapore Ministry of Foreign Affairs for many years. Among other things, he was ambassador to Cambodia, Malaysia, the United States, and for ten years to the United Nations. He is currently a professor of political science at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University in Singapore. He wrote his book in collaboration with political scientists from renowned American and British universities.

His book is pleasant to read because Mahbubani is familiar with both worlds and does not take a one-sided position. He writes as a friend of America as well as of China. Thus, after the introduction, the text begins with two detailed chapters, “China’s Biggest Strategic Mistake” (pp. 25-48) and “America’s Biggest Strategic Mistake” (pp. 49-78). America lacks a comprehensive strategy for dealing with China, he writes, and there have often and for various reasons been misunderstandings in dealing with the American business community. The causes of these lie in the system and Chinese officials have often failed to counteract them. As an advocate of globalisation, Mahbubani analyses these contexts thoroughly and points out the consequences. He returns to this problem again and again in the following.

Is the communist party a discontinued model also in China?

Mahbubani: “The Chinese Communist Party is not run by doddering old apparatchiks. Instead, it has become a meritocratic governance system, which chooses only the best and brightest to be promoted to the highest levels. The CCP is not perfect. No human institution is. […] Yet, it is also a fact that relative to its peers around the world, the Chinese governing class generates more good governance (in terms of promoting the well-being of its citizens) than virtually any other government today. Since the Chinese Communist Party is constantly vilified in the Western media, very few people in the West are aware that the members of this Communist Party have delivered the best governance China has ever enjoyed in its entire history.” (p. 140)

“The greatest source of misunderstanding of the CCP arises when the West focusses on the word Communist instead of the word Chinese. Although the Chinese have not succeeded in creating a perfect governance system, theirs does reflect thousands of years of Chinese political traditions and wisdom. The overall weight of the Chinese government on the Chinese people is not a heavy one. The CCP does not actively interfere in the daily lives of its citizens. Indeed, the Chinese people have enjoyed more personal freedom under the CCP than any other previous Chinese government.” (p. 172)

“Yet, in the eyes of many objective Asian observers, the CCP actually functions as the ‘Chinese Civilisation Party’. Its soul is not rooted in the foreign ideology of Marxism-Leninism but in the Chinese civilisation.” (p. 7)

Is China really threatening the free world?

Mahbubani: “The latent fear of the yellow peril surfaces from time to time in literature and art. As a child living in a British colony, I read the popular Fu-Manchu novels. They left a deep impression on me. Subconsciously I began to believe that the personification of evil in human society came in the form of a slant-eyed yellow man devoid of moral scruples. (p. 260)

“In America, the political course towards China is dominated by a gloomy view – of China as an oppressor, an image reinforced by a very real, subconscious fear, a fear that the American public used to call the ‘Yellow Peril’. You don’t hear the term much anymore, but the sentiment continues to resonate strongly.” (German foreword, p. 8)

“Americans tend to believe that good always triumphs over evil and that no political system is inherently as good as what the founders of their republic had in mind. This could also explain why the demonisation of China has increased so much in recent years. The more China is made out to be a bad actor (especially as China defied America’s expectation that it would open up progressively and transform itself into a democratic society as it moved closer to America), the easier it has become for America to cling to the belief that sooner or later it will triumph over China, regardless of what the chances actually are.” (German introduction, p. 27)

Are political and personal freedoms lacking in China?

Mahbubani: “America is the only developed society where, over the past 30 years, the average income of the bottom 50 percent of the population has gone down over the past thirty years. In the same period, the Chinese people have experienced the greatest improvement in their standard of living ever seen in Chinese history. The obvious American retort to such a statement would be to say that the Chinese still don’t enjoy the political rights that Americans do. That is true. Yet, it is also true that the Chinese people cherish social harmony and social well-being more than individual rights.” (p. 152)

“Given the absence of political freedom in China – the Chinese people clearly don’t have the freedom to organise political parties, speak in a free media and vote for their leaders – the assumption in the West is that the Chinese people must feel oppressed. However, the Chinese people don’t compare their condition with that of other societies. Instead, they compare their lot with what they experienced in the past. And all they can see is that they have experienced the largest explosion of personal freedom ever experienced in their history. When I first went to China in 1980, the Chinese people couldn’t choose where to live, what to wear, where to study or what jobs to take.” (p. 153)

“Today’s China is a happy society. That is also why the 130 million tourists who travelled abroad in 2019 returned home voluntarily and feeling good. But in America, the political course toward China is dominated by a gloomy view – of China as an oppressor.” (German foreword)

What is striking is that the likelihood of being jailed is at least five times higher in America than in China. (cf. p. 161)

Does the West need to teach China democracy and human rights?

“Americans hold sacrosanct the ideals of freedom of speech, press, assembly and religion and also believe that every human being is entitled to the same fundamental human rights. The Chinese believe that social needs and social harmony are more important than individual needs and rights and that the prevention of chaos and turbulence is the main goal of governance” (p. 276)

“Yet, a fundamental contradiction would only arise in this area if China tried to export its values to America. [...] China’s leaders are political realists. They would not waste their time or resources on a mission impossible. Sadly, the same is not true in the American political system.” (p. 276 f.)

In reality, so-called democracy promotion from the West can have "… the opposite effect of what the theory suggests. It can destabilise and weaken societies instead of strengthening them. [...] Against this recent historical backdrop, it would be reasonable for many Chinese leaders to believe that when America promotes democracy in China, it is not trying to strengthen China. It is trying to bring about a more disunited, divided China, a China beset by chaos. If that were China’s fate, America could continue to remain the number one unchallenged power for a century or more. Such a Machiavellian goal, may seem far-fetched. Yet, it would be a perfectly reasonable move for a great power if it believes that its primacy is being challenged.” (p. 179)

On the subject of “human rights abuses”: Most Americans are unaware that China experienced moments similar to 9/11, “when terrorists recruited from the Xinjiang region went on a killing spree in several cities. (p. 280) There were numerous attacks in Xinjiang with several hundred deaths. Mahbubani shows in detail that the sometimes-rigorous measures China has taken are more moderate than the “war on terror” waged by the US, which has been life-threatening for millions. Many innocent civilians have lost their lives. America has no reason to blame China in any way. It would be more appropriate, Mahbubani says, for the US itself to pay more attention to human rights and to renew and nurture its own democracy. (pp. 276-280)

Is the Chinese government so authoritarian that it does not deserve any trust?

Mahbubani: "… the Chinese people trust their government. This is confirmed by independent international surveys. The (US American) 2018 Edelmann Trust Barometer report, which surveyed trust levels in several different countries, found that in terms of the domestic population’s trust in their government, China ranked top, while America ranked fifteenth.” (p. 154)

A wise Chinese government in the 21st century knows that it must balance three sometimes conflicting parts to ensure a healthy society: growth, stability and personal freedom. And: “According to a 2015 Pew survey, 88 percent of Chinese believe that when their children grow up, they will be better off financially than their parents, compared to a median of 51 per cent amongst other emerging countries and 32 per cent in the United States.” (pp. 157f)

“… every Chinese government has known for millennia that if the vast majority of the Chinese people choose to revolt, no amount of repression can hold them down.” (p. 156)

If a widespread revolt breaks out, the Chinese emperor will lose his “mandate of heaven”. Mahbubani mentions the writings of Mencius, a disciple of Confucius, as an example. Mencius explained the Chinese concept of the Mandate of Heaven as follows: “The ruler of a state was established by heaven for the benefit of the people. The ruler possessed the mandate of Heaven only as long as he retained the support of the people, for it was through the ‘heart’ of the people that Heaven made its will known. The people, in turn, could rightfully hold their rulers to account. They had the right to banish a bad ruler and even to kill a tyrant.” (p. 157)

Is China really threatening its neighbours …?

“The more powerful China has become, the less it has intervened in the affairs of other states.” (p. 144)

Mahbubani: "… relative to its size and influence, China is probably the least interventionist power of all the great powers. Of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, China is the only one that has not fought in any foreign wars away from its borders, since World War II. America, Russia, the UK and France have done so. As this book has documented in several areas, the primary goal of China’s rulers is to preserve peace and harmony among 1.4 billion people in China, not try to influence the lives of the six billion people who live outside China. This is the fundamental reason why China is behaving like a status quo, rather than as a revolutionary power. In so doing, it is delivering a global public good to the international system.” (p. 148f)

“Since all the immediate neighbours have lived next to China for thousands of years and have long developed sophisticated and subtle instincts on how to manage a rising China. And the Chinese elite (unlike the American elite) has a deep understanding of their long history with their neighbours. There will be many back-and-forths between China and its neighbours. [...] But there will not be wars.” (p. 93)

… and Taiwan and Japan in particular?

The history behind it: The 19th century was a century of raids by the West and also by Japan. Here are a few key words: British, French, German and American troops invaded China and occupied it in parts. China, which had been self-reliant and peace-loving for centuries, was no match for them. In two wars, the British forced China to accept opium (from India) as a means of payment for their imports from China (tea, porcelain). China had to surrender Hong Kong and later ceded it to Britain by treaty for 100 years (until 1997). In 1860, 4,500 British and French soldiers completely destroyed, pillaged and plundered the huge imperial palace with its thousands of shrines and cultural assets. The palace was about eight times the size of the Vatican. (see p. 138)

However, no other country’s relationship with China is as strained as that of Japan. Long-term military occupation and massacres among the civilian population are keywords in this context. This also includes the annexation of Taiwan.

Mahbubani: “Nearly all the historical vestiges of this century of humiliation have been removed or resolved, including Hong Kong and Macau. Only one remains: Taiwan. It was Chinese territory until China was forced to hand it to Japan after the humiliating defeat in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895.” (p. 94) This annexation was later recognised by the Allies in the Treaty of Versailles after the First World War.

“America cannot claim that it doesn’t understand the significance of Taiwan. It was clearly the hottest issue to resolve when Nixon and Kissinger began the process of reconciliation with China. Many clear understandings were reached between America and China. The most explicit understanding reached was that Taiwan and China belonged to one country. The 1972 joint communique stated: ‘The US side declared: The United States acknowledges that all Chinese on either side of the Taiwan Strait maintain there is but one China and that Taiwan is a part of China.’ […] The Chinese desire to reunite Taiwan with the mainland represents a restitution, not an expansion.” (p. 95)

That today’s China could threaten Japan is absurd – also in view of its close involvement in the military structure of the USA.

Will the world descend into barbarism and chaos if America withdraws?

Mahbubani: “Having dealt with Chinese officials since I began my diplomatic career in 1971, almost fifty years ago, I have been astonished how the quality of mind of Chinese diplomats has improved, decade by decade. Sadly, for different reasons, the trajectory of the American diplomatic service is in the opposite direction.” (p. 141)

The fact that there is still a strong militarisation of USA foreign policy leaves little room for diplomacy. Sanctions are quickly imposed on countries that behave insubordinately. Weapons are quickly supplied and military “solutions” are favoured (which usually make situations worse). This manifests itself in the finances of the US government: “… the budget of the State Department ($31.5 billion) is truly miniscule compared to that of the Defence Department ($626 billion).” (p. 123f)

The USA spends more on the military and on its huge arms industry (military-industrial complex) than all the other countries in this world put together, and that is – according to Mahbubani – not necessarily socially and economically beneficial: “America's massive arms budget gives the country the same advantage that a dinosaur gets from its massive body – not a very big one.” (German foreword, p. 10)

“Having been burnt in Iraq and Afghanistan, the logical response of America, if it were supple, flexible, and rational, would be to walk away from getting involved in unnecessary conflicts in the Islamic world. The inability to make this U-turn demonstrates that, like the old Soviet Union, America has become rigid, inflexible, and doctrinaire.” (p. 115)

“There is no danger of America collapsing like the former Soviet Union. America is a much stronger country, blessed with great people, institutions, and many natural advantages. However, while America will not totally collapse, it can become greatly diminished, a shadow of itself.” (p. 128)

“America has done more right than it has done wrong. This explains the relatively good relations America has had with most countries in the world. Yet, it is also true that America has made several unnecessary and painful mistakes, especially with the Islamic world and with Russia.” (pp. 250f.)

“If George Kennan were alive today, he would clearly see that America has been deeply wounded, internally and externally, by its involvements and unnecessary conflicts in the Islamic world.” (p. 115) George Kennan was a respected strategist in the 1950s who designed the USA’s containment policy against the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

Is China getting a dictator for life in the person of Xi Jinping?

Mahbubani: “After Xi Jinping removed the term limits on his presidency, he continued to remain popular in China. The long history of China has taught the Chinese people a vital lesson: when the country has weak leaders, it falls apart. [...] The removal of term limits, for which he was roundly criticised, may turn out to be one of the biggest blessings that China has had. And it may be one critical reason why China wins the contest against America.” (p. 180)

Mahbubani mentions Plato (427–347 BC), the “forefather of Western philosophy”. A lot of people in the West today hold that democracy is the best form of government. Plato, after his mixed experience with popular rule in Greece, concluded that the best form of government was that of a philosopher-king. Mahbubani: “There is a very strong potential that Xi Jinping could provide to China the beneficent kind of rule provided by a philosopher king.” (p. 180)

Is China’s development policy a threat to the free world?

“Now it is China, not America, that is taking the lead in building a new multilateral architecture, including the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). America opposed both these initiatives. This didn’t stop many of its key friends and allies from joining them.” (p. 52)

“If America is going to respond effectively to the new geopolitical challenge from China, it needs to make some massive U-turns, including cutting down its military expenditures, withdrawing from all military interventions in the Islamic world, and stepping up its diplomatic capabilities. Yet, powerful vested interests in America will make it impossible for America to make any of these sensible U-turns.” (p. 128)

“The best partner to work with to develop Africa is China. Indeed, China has already emerged as the largest new economic partner of Africa.” (p. 222) “The emergence of China does not pose a threat to Europe. Indeed, it could help to enhance Europe’s long-term security if China promotes Africa’s development.” (p. 223) “If economic and political conditions in the African continent don’t improve in the twenty-first century, Europe can expect tens, if not hundreds, of millions of Africans to knock on its doors seeking a better life in Europe.“ (p. 220)

Conclusion: “… make the world safe for diversity”

(John F. Kennedy). (p. 276)

“Chinese communism is not a threat to American democracy. Instead, the success and competitiveness of the Chinese economy and society is the real challenge.” (p. 271)

“China’s role and influence in the world will certainly grow along with the size of its economy. Yet, it will not use its influence to change the ideologies or political practices of other societies. One great paradox about our world today is that even though China has traditionally been a closed society, while America purports to be an open society, the Chinese leaders find it easier than American leaders to deal with a diverse world, as they have no expectation that other societies should become like them.” (p. 254f)

In this comprehensive work, Kishore Mahbubani does an excellent job of including China’s “soul”, shaped by its history and culture, in his analysis. It is to be hoped that American politicians and the media in particular – but also the Western world as a whole – will read this book and learn something new. In our times of simmering trade wars and conflicts, Mahbubani's book is an appeal to reason and an indispensable guide to better understanding the rising power China. Mahbubani: “If America and China were to focus on their core interests of improving the livelihood and well-being of their citizens, they would come to realise that there are no fundamental contradictions in their long-term national interests.” (p. 281) “If the two superpowers were to co-operate, miracles could come true.” (German foreword, p. 17) And: “… there is enough space in the world for both America and China to thrive together.” (p. 281) •

Sources:

Mahbubani, Kishore: Has China Won? The Chinese Challenge to American Primacy Public Affairs, New York. Printing 4, 2020; ISBN 978-1-5417-6813-0 (Hardcover); quotes in the article with friendly permission of the author

Mahbubani, Kishore. Hat China schon gewonnen? Chinas Aufstieg zur neuen Supermacht. Deutsche Übersetzung 2021; ISBN 978-3-86470-773-5

Kissinger, Henri. China. New York 2011

Nass, Mathias. Der Drachen Tanz – Chinas Aufstieg zur Weltmacht und was er für uns bedeutet. (The Dragon’s Dance – China’s rise to world power and what it means to us) Munich 2021

Durant, Will und Ariel. Kulturgeschichte der Menschheit. (The story of civilisation) vol. 2, New York 1963

Seitz, Konrad. China. Berlin 2002

On the importance of Confucian culture

ww. Kishore Mahbubani points out in several passages that China is the only one of the great cultural nations in history that still exists today after four collapses. Central to our understanding is Confucius with his teachings.

Confucius was a Chinese sage who lived in the second half of the 6th century BC. After extensive reading and meditation, the scholar decided to give up his official duties in order to devote himself to the education of his fellow men. His wisdom and philosophy made him famous all over the country. His teaching, which is based on observation and common sense and always keeps an eye on practical application, has dominated Chinese society to this day. The doctrine of decency and respect for one’s fellow men was intended to develop character and a social order. The Chinese emperors had his teaching carved in stone and declared it the state religion. The American Will Durant, who examined and compared the diverse cultural history of mankind in twenty volumes: “The stoic conservatism of the ancient sage sank almost into the blood of the people, and gave to the nation, and to its individuals, a dignity and profundity unequalled elsewhere in the world or in history.”

A highly educated civil service, to which everyone had access after lengthy, demanding exams, was responsible for the administration. Feudalist structures or a church like that in the West did not exist and do not exist.

“With the help of this philosophy China developed a harmonious community life, a zealous admiration for learning and wisdom, and a quiet and stable culture which made Chinese civilisation strong enough to survive every invasion, and to remold every invader in its own image.” (Durant, vol. 2, p. 52) It is interesting that the Venetian Marco Polo, who travelled to China 800 years before Durant, reported something very similar.

“For Mencius [student of Confucius] as well as for all his successors, government was always government for the people, never through the people. The virtuous and educated take care of the people. The idea that the (uneducated) people could look after themselves in a democratic state would never have occurred to any Confucian.” (Seitz 2002, p. 46)