“Rats do sleep at night”

by Peter Küpfer

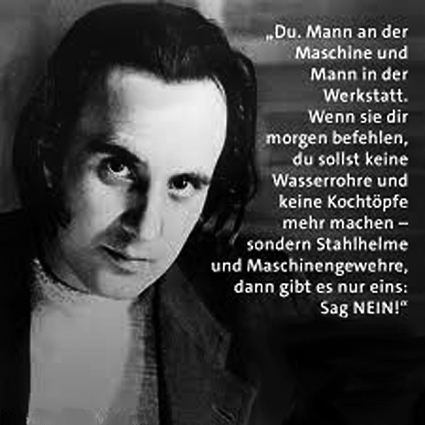

It is a good time to re-read Wolfgang Borchert. When I was a student, reading the works of Wolfgang Borchert, the author who sadly died far too early, was required. In his post-war short prose, he writes from the victim’s perspective and relays a serious, deeply human warning. We should take it seriously.

He lived a short life. Born in 1921, Wolfgang Borchert was twelve years old when Hitler took power in Germany. During this time Hitler strengthened his control especially by nazifying the schools. In 1939, when he was 18, the war which was based on a lie, started (the lie was an alleged “Polish attack” on Germany faithfully and tightly spread by the film newsreels). He quit his apprenticeship as a bookseller and got into acting. After the initial German frenzy of quick victories and the defeat of the arch-enemy France came the battle of Stalingrad. And then came the “total war” provoked by Goebbels’ diatribe in the Sports Palace where he manipulated the civilians into supporting this war. The young writer was drafted alongside other comrades in fate, and sent to the Russian front with the armored infantry even though he wasn’t healthy. From the front he wrote critical letters to his mother in Hamburg. These letters were discovered and formed the pretext for arresting the irregular thinker as a deviant and “Wehrkraftzersetzer” (someone who undermines military force).

Race with death

At this point he was already diagnosed with the fatal disease. He succumbed to the illness in 1947. He was tried by a military court and was sentenced to death. The Rilke admirer escaped the death sentence due to extenuating circumstances. Instead, he was sent to the Russian front. Due to his frail health, this young man was not going to help to win a lost war. On the eve of his discharge from the Wehrmacht, a “comrade” blew the whistle on him because of his daring jokes about militarism. New incarceration, new procedures, this time in Berlin-Moabite. In the meantime, the Allied troops were moving closer. When the Red Army occupied parts of Berlin in spring 1945, he managed to escape. Protected by Allied tanks advancing to the northwest, the exhausted Borchert walked to Hamburg. Mentally and physically at the end of his tether, he arrived in the bombed-out city, “a man marked by death, but gratefully received as one freed from death”, as his friend and mentor Bernhard Meyer-Marwitz wrote in his epilogue to the 350-page one-volume complete works of Borchert, published by Rowohlt in 1949. This light and small book is a heavy read.

The hectic race for survival continued under different circumstances. This time the nascent writer had to contend with a war-shattered Germany as well as his progressing illness. Despite the most adverse circumstances in the year zero (fortunately he had supportive friends), the young writer mustered all his strength to write. The subject was the war; however it wasn’t about the damaged souls. It was about what drove people to support this war. His sharp-edged poems, his fragmentary language had only one aim: to document the shattering of Germany, the inner as well as the outer. Somewhat linguistically reminiscent of Expressionism, which had attempted something similar in the face of Germany's first major catastrophe, the First World War, his writing was often a single cry. A veteran was not only describing what he had seen and suffered, he was the suffering itself in words. Many carried it within themselves, were marked by it, whether consciously or unconsciously, whether “wanted” or unwanted – a collective trauma.

The man outside

Even before the publishing of newspapers and books was possible post-war, the radio was broadcasting. Therefore, audio drama experienced previously undreamed-of triumphs on the radio. Thus, Borchert’s play “The Man Outside” (Draussen vor der Tür), which was written in only eight days in a burst of energy, with the significant subtitle “A play that no theatre wants to play, and no audience wants to see”, was first heard on the radio as an audio drama. Nordwestdeutscher Rundfunk produced the play as a radio play in its Hamburg studio and broadcast it on 13 February 1947. It had an unexpectedly strong impact and was repeated several times. It met with harsh rejection (Nihilism!) as well as enthusiastic approval, especially in military and soldier circles (That’s how it was, that’s how it is!). Someone had found a language for the outer and spiritual world. Someone had found a language for the external and spiritual hardship of the time, both for those who stayed here and for those who returned home, for whom there was often hardly any room in the soul at the time. “All of us who still walk around in recoloured military clothes, wear gas mask goggles, clear rubble and go dancing [...], at whose bedsides the dead comrades squat at night and torment us with the gaze of their extinguished eyes, who are everywhere in the way and stand aside, we have once again heard our own voice, which one of us has formed into words,” wrote one of the German returned front-line soldiers in one of the numerous letters to the author. And another, in the face of the cheap consolation “In fifty years it will all be over”: "In fifty years it will not all be over. In fifty years, it will be as much the present as it was today and yesterday. It is not there to deceive us, not to forget it – forgetting is the worst thing for man, no, to master it.” (Wolfgang Borchert. The Complete Works. Rowohlt 1947, Hamburg, epilogue p. 342 f.) At the centre of the plot of “Outside the Door” is the former sergeant Beckmann. He cannot get over the fact that he lost eleven of his men in enemy fire during a so-called “suicide mission”. He does not want to and cannot take responsibility for this. One of the most impressive scenes is the visit of the homeless returnee to the undamaged villa of his colonel, who at the time had given him the order for the hopeless reconnaissance mission into the enemy lines. The commander is supposed to take back his responsibility and bear it, he himself can no longer do it now. He wants to sleep at least one night again, without nightmares. The colonel is completely focused on reconstruction, he has successfully suppressed his own war experiences. That’s all over now, a little optimism, and then we’ll get it done, that’s his way, with which he fights unsuccessfully against Beckmann's stubbornness. Beckmann is told to go to the garage, wash and shave there, let the chauffeur give him an old one of his suits and then leave them alone: “First become a human being again!” he says to the physically and mentally burnt-out soldier. However, he has already left this place of strength of German reconstruction.

Borchert’s play shows the extent of the destruction in oppressive symbolism. It gets under your skin because this destruction is not only external, but also internal. All the stages of Beckmann's return to normality fail because not only the soldiers, but also the inhabitants far from the fronts (on the “home front”, as it was called at the time) suffered from the war, also emotionally.

Unshakeable humanity

Borchert’s seismographic exploration of what nonetheless survived in terms of fellow humanity comes across as factual as his inventory of the suffering of the time. For me, this is most vivid in his short prose sketch, which was called a short story at the time, “Nachts schlafen die Ratten doch” (Rats do sleep at night).

The setting is one of those streets in Hamburg, Berlin or Dresden where heaps of rubble on the left and right indicate that houses once stood here. Paths that the survivors have made lead through the rubble landscape. Nine-year-old Jürgen sits on a pile of rubble, his face defiant, holding a strong club in his hand. An old man laboriously makes his way through the rubble, a basket with a lid on his arm, sees the boy, pauses, speaks to him cautiously. The dialogue is as fragile as the surroundings and the boy's soul, which the old man notices immediately. Little by little, chunks of content make their way through the fragile dialogue. The boy sits here because he must sit here. He doesn’t say why. But he must sit here, right here. Required. Yes, even at night, especially at night. The old man tries to make him curious. Whether he can guess what he has here in the basket. No problem for the boy, who already knows life: grass, rabbit food. That's right. Whether the boy doesn’t want to see his rabbits, the hutch is not far away. And now there are young ones. No, I can’t. Well then ... When the old man turns away, the boy quickly says: “It’s because of the rats.” Rats? “Yes, rats. They eat from the dead. From people”. How would he know that? From his teacher. That’s his brother down there. A bomb hit the house. Everything was gone, and then his brother too. He was much younger than him, only four. He must be down there somewhere. And that’s where Jürgen must sit and chase the rats away. The old man resorts to a white lie to save the boy and shakes his head at teachers who tell their children nonsense, even though it is common knowledge that rats sleep at night. Tired and relieved, the child sighs. When leaving, the possibility of coming along is looming. When the old man comes back, after feeding his rabbits. Then the boy can also go to the parents (because, as we know, the rats sleep at night). And before that he shows him his rabbits. He can then take one of them with him. A white one, the boy wishes...

Borchert’s legacy, his play “The Man Outside”, was performed after all. The premiere was on 16 February 1948 at the Hamburg Kammerspiele. It was soon included in the repertoires of thirty German-language theatres. Before the premiere in Hamburg, the play’s director, who had known Borchert personally, appeared before the audience. She had just received the news that Wolfgang Borchert had died the day before as a result of his serious illness in a private clinic in Basel, where he had been cared for by his friends. •

“The rats do sleep at night” translated from the German by Robert Painter: https://exchanges.uiowa.edu/issues/topographies/rats-sleep-at-night/