The “Asia Minor Catastrophe”

A Greek granddaughter’s search for clues

by Renate Dünki

Greece, for many a sunny holiday destination with hospitable people, has a fragile history that we are hardly aware of. A slim book* that has just been published with the subtitle “A Pontic Search for Traces” picks out a momentous period of time. Which traces are meant? In her memoir, the Greek author Maria Topali approaches the tragic fate of many “Greeks abroad” in the 1920s. The so-called Asia Minor Catastrophe is still a trauma for Greece today, and it continues to determine attitudes towards Turkey.

100 years ago, a “population exchange” was agreed in Lausanne, actually the final expulsion of all Greek Orthodox Christians from the former Ottoman Empire and, conversely, the “repatriation” of people of the Muslim faith, now Turks, to Kemal Atatürk’s newly created state entity. This was after thousands had already died in labour battalions, on extermination marches or through massacres. The goal was an ethnically homogeneous nation state freed from minorities – after long battles for territories in and around today’s Turkey, in which Balkan states and Greece were also involved. Ideas that still play a role today and can be instrumentalised for proxy wars.

Nation state without minorities

For centuries, Greeks, Armenians and Jews had lived more or less peacefully side by side in the Ottoman multi-ethnic state. The religious minorities remained unmolested as long as they subordinated themselves to the Ottoman Empire. The Pontians on the southern shore of the Black Sea were descendants of merchant Greeks who had settled there since about 800 BC. They were christianised in the Byzantine Empire and saw themselves as descendants of their own Christian Byzantine Empire of Trebizond (13th century to 1461), with their own ancient language (Ancient Greek, Turkish and other parts) and culture. After the Balkan Wars (1913), they were increasingly driven out of their settlements by the Turkish military, taken prisoner, their houses destroyed.

All survivors had to find accommodation and a livelihood in Greece in 1923. Refugee at that time meant: someone from Pontus or Asia Minor.

The resettled people now made up a quarter of the population of Greece – an extreme challenge. New settlements were built for them, often in northern Greece, and land was made available – not without great difficulties, as one can imagine.

A Pontic search for traces

The author Maria Topali comes from a Pontic family, two-thirds of whose members perished at that time. Her grandmother had survived the expulsion, her grandfather had escaped from a camp and been rescued. The majority of the men, women and small children lost their lives.

Through her nanny and grandfather, Maria Topali learned the archaic Pontic language and experienced the constant change between Modern Greek and Pontic. Her mother and the sister of which were the main sources of her knowledge of the family history and the fate of her relatives. Many survivors did not speak of the atrocities and horrors they endured, but the author persevered in asking questions about their origins and in her research.

Her account is characterised by the finest observations and recollections, by sensitivity, but also scientific accuracy. All statements are supported by credible sources; Maria Topali never allows herself to be seduced into one-sided judgements. She always includes the complex historical situation in the description of her roots and names atrocities and victims on both sides. And she does not limit herself to the actual catastrophe, but goes into the before and after.

She takes on this huge task of spreading out such a period of time, such a theme, in a way that is all her own and not always easily accessible. “Those who wait impatiently for extended stretches of narrative [...], astride a solid chassis of certainties, had better pause here. My story moves slowly, on frail legs, afflicted with doubts, missteps and setbacks. Again and again a detail catches my attention [...]”. Those who have this patience, however, experience a fascinating text that also illuminates the “social capital” of this family: the credo of the surviving women, who at that time could already all read and write and become employed, thus had “their own purse”. “Tough, tough women. The whole kind of people/breed is like that, with them you could recreate the whole world all over again.” (p. 59)

Active people

I was particularly attracted by the depictions of the beloved nanny, but also of the grandfather. This Pontic grandfather, Nikolakis, was a trained teacher, but as a young man he had decided to learn the advanced European way of beekeeping – he became a beekeeper. He passed on his knowledge after the resettlement, travelling from village to village to make it known, and even as an 80-year-old man he still published his bee magazine. The mailing took place every month in the family home in Thessaloniki with the help of the relatives, after which it continued as a games evening (p. 65). The grandfather is an example of how enriching the reception of refugees was for bitterly poor, backward Greece at that time: the country owed many innovations in agriculture, industry or music to the reception of these brisk, capable people. The grandfather radiated humour and joie de vivre. Refugee also meant: one who builds an existence from nothing.

This multi-layered prose part of the search for traces is complemented by a second part with a selection of poems. For Maria Topali is very well known in Greece primarily as a poet. The poems with their power of association revolve around experiences of farewell and loss, love, memory and the passing on of cultural values in the family. They presuppose a certain knowledge of the Greek background on the part of the reader; footnotes facilitate understanding. The texts testify to the author’s impulse to approach her story from the inside.

The indispensable explanations of the Asia Minor Catastrophe by Mirko Heinemann shed light on this largely unknown chapter of Greek, but also Asia Minor history.

A not so easily accessible multi-faceted book. Whoever gets involved can take a look into an unknown world, from which many questions also arise for the present. •

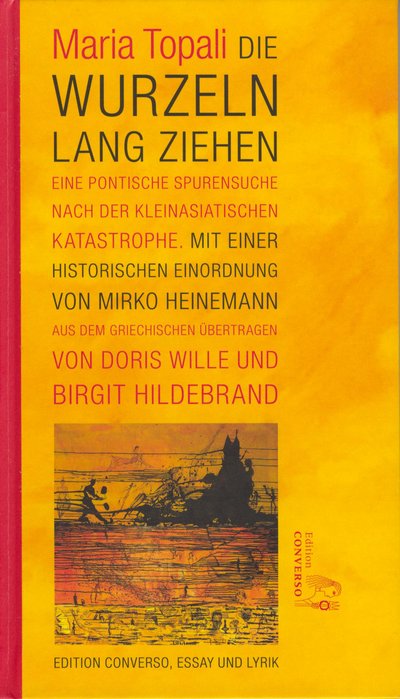

* Topali, Maria. Die Wurzeln lang ziehen. Eine pontische Spurensuche nach der Kleinasiatischen Katastrophe. Edited by Monika Lustig. With a historical classification by Mirko Heinemann. Translated from the Greek by Doris Wille and Birgit Hildebrand. Karlsruhe 2023, Edition Converso, ISBN 978-3-949558-11-5